|

Return to the Index Map for My Trip to England |

On this page you'll find all of the pictures I took on my various walks around London. These spanned all or parts of three separate days.

October 7

After checking in to the Chelsea Hotel, I had to grab some sleep, and by the time I went out for a walk it was mid-afternoon. The light rain that had greeted me when I got into the city earlier in the day was still falling. I did take my umbrella with me when I went out of the hotel, turned north on Sloan Street, and walked north, crossed Knightsbridge Street, and walked on into Hyde Park. But the afternoon was so rainy, that I only walked around a little while (basically just to get some exercise) before returning to the hotel. I spent the evening in the hotel, eating in the restaurant downstairs. By the next morning, I was pretty much adjusted to London time.

October 8

The weather is overcast today, but at least it isn't raining (other than a couple of brief showers that I waited out in a store or restaurant). So I expect to get some decent pictures.

|

I had one of those little tourist maps with me that I had gotten at the hotel, and I just went out to see what I could see. I already knew that to really experience London, one would have to spend a good deal of time here, but then that is true of just about any major city anywhere in the world.

But I only had a couple of days to myself here in the city, and I thought that I would just try to see the major monuments, buildings, and sights that I have heard about all my life. At right is an aerial view of the part of London that I traversed on foot today, and I have marked most of the sights that I took pictures of.

I had to eschew going into museums and churches for that would have taken up too much time- particularly since I was walking from place to place rather than being on a tour and chauffered around. So this was just a chance for me to hit the high points, but I was under no illusion that I would come away from today and tomorrow with a thorough appreciation of London, its history, its culture, or its people.

But I thought that surely I would return to this city in the future, in some situation when I would have much more time to delve deeper into the city's rich and ancient history. With that thought in mind, I headed out from the Millennium Hotel to see what I could see.

|

Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch that was designed by John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it originally stood about a mile from here at the northwest corner of the original palace grounds. Nash's three arch design is based on those of the Arch of Constantine in Rome and the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in Paris. The triumphal arch is faced with Carrara marble with marble embellishments. Sadly, less than twenty years in the poor and polluted London atmosphere if the early 19th century was sufficient to destroy the light coloring of the original Carrara marble.

In 1851 on the initiative of architect and urban planner, Decimus Burton, one time pupil of John Nash, it was relocated to its current location at the junction of Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Edgware Road. In the 1960s, Park Lane was widened, and a large traffic island created at the three-street intersection. Marble Arch is now, incongruously isolated in that traffic island. Admiralty Arch, in Holyhead, Wales, is a similar arch, and it, too, has been sadly (and even more so than Marble Arch) cut off from easy public access.

The arch is 45 feet high, and measures 60 feet wide by 30 feet deep. They are hard to see, but there are wrought-iron barriers that prevent you from walking through the arch. I wondered why, only to discover that just members of the Royal Family and the King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery are said to be permitted to pass through the arch; this happens in ceremonial processions. The arch gives its name to the area surrounding it, particularly the southern portion of Edgware Road and also to the underground station. The arch is not part of the Royal Parks System, and is maintained by local authorities.

From the Marble Arch, I walked southeast down Park Lane, one of London's storied addresses. Park Lane separates Hyde Park to the west from Mayfair to the east. The road has a number of historically important properties and hotels and has been one of the most sought after streets in London, currently home to a number of politicians, business moguls, and celebrities. Eventually, I arrived at Hyde Park Corner, the intersection of Knightsbridge, Piccadilly and Grosvenor Place. That's where I found the Wellington Arch.

|

Both the Wellington Arch and Marble Arch were planned in 1825 by George IV to commemorate Britain's victories in the Napoleonic Wars, and would be part of a project to make the Hyde Park area a rival to European capital cities; the arch would be a triumphal approach to the recently completed Buckingham Palace. The goal was an urban space dedicated to the celebration of the House of Hanover, national pride, and the nation's heroes.

|

Instead, the arch was topped with an ungainly equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington by Matthew Wyatt (at 40 tons and 28 feet high, the largest equestrian figure ever made. Hardly anyone liked it. It was too large; it wasn't all that good; it had to be placed sideways. Burton had envisaged a smaller quadriga, and many supported his idea. Despite the objections of every member of Parliament save one, the Government placed the Wellington statue on the arch in autumn 1846; when the scaffolding around the arch was removed, the outcry intensified; almost every critic though the statue a blemish on the arch, on London, and on the English.

The critics finally got their way when, during 1882, traffic congestion at Hyde Park Corner required that the arch be moved to the top of Constitution Hill to create space for traffic. When this happened, Wyatt's incongruous statue was removed to Aldershot, and its place on Burton's arch was occupied by a Quadriga (simpler in design than Burton intended) by Captain Adrian Jones. The sculpture depicts Nike, the winged goddess of victory, descending on the chariot of war, holding the classical symbol of victory and honor, a laurel wreath. The statue is the largest bronze sculpture in Europe.

|

The site of Trafalgar Square had been a significant landmark since the 13th century and originally contained the King's Mews. After George IV moved the mews to Buckingham Palace, the area was slowly redeveloped, and the square finally opened in 1844. The square has been used for community gatherings and political demonstrations, including Bloody Sunday in 1887, the culmination of the first Aldermaston March, anti-war protests, and campaigns against climate change. The London Christmas tree is set up here, and New Year's celebrations are held here as well. The square is also famous (or infamous) for its huge number of feral pigeons.

At the center of the square is one of London's most famous landmarks- the 169-foot Nelson's Column (and the four lion statues that surround it); other commemorative statues and sculptures occupy the square as well. Nelson's Column commemorates Admiral Horatio Nelson, who died at the Battle of Trafalgar. The monument was constructed between 1840 and 1843 at a cost of what today would be some $5 million. It is a column of the Corinthian order built from Dartmoor granite. A sandstone statue of Nelson tops it, and the four bronze lions at the base were added in 1867.

The pedestal is decorated with four bronze relief panels, each 18 feet square, cast from captured French guns, depict the Battle of Cape St Vincent, the Battle of the Nile, the Battle of Copenhagen, and the death of Nelson at Trafalgar; each was created by a different artist. These were completed in 1854.

Nelson's Column was planned independently from the creation of the square itself; the monument was first proposed in 1838, to be funded by public subscription. A competition was held and the design we see today was the winner (although the public at large was less enthusiastic). The column was completed and the statue raised in November 1843.

The last of the bronze reliefs on the column's pedestals was not completed until May 1854, and the four lions, although part of the original design, were only added in 1867. Charles Barry, the architect of the square itself, did not want the column erected; he thought the square would be more open and welcoming without it. Had he lived long enough, and had history turned out a bit differently, he might have seen the entire column removed to Berlin by the Nazis; a plan for doing so after a planned invasion of Britain was uncovered after the war.

|

|

|

Trafalgar Square is one of the most visited sites in London, and not just for Nelson's Column and the pigeons. Adjacent to the square are two more of London's most visited landmarks.

|

The earliest extant reference to the church is from 1222, with a dispute between the Abbot of Westminster and the Bishop of London as to who had control over it. The Archbishop of Canterbury decided in favour of Westminster, and the monks of Westminster Abbey began to use it. Henry VIII rebuilt the church in 1542 to keep plague victims in the area from having to pass through his Palace of Whitehall. At this time, it was literally "in the fields", an isolated position between the cities of Westminster and London.

By the beginning of the reign of James I, the church had become inadequate for the size of its congregation, so in 1606 the king granted more land to the church so it could expand; at the same time, it was "repaired and beautified". Later in the 17th century galleries were added inside. As it stood at the beginning of the 18th century, the church was built of brick with stone facings, was 84 feet by 62 feet with a 90-foot tower.

A survey of 1710 found that the walls and roof were in a state of decay, so in 1720, Parliament passed an act for the rebuilding of the church, and James Gibbs was selected to design it, and he produced a simple, rectilinear plan. The foundation stone was laid on 19 March 1722, and the last stone of the spire was placed into position in December 1724. The total cost was £33,661 including the architect's fees.[5] The west front of St Martin's has a portico with a pediment supported by a giant order of Corinthian columns, six wide; the order is continued around the church by pilasters. Gibbs drew on Christopher Wren's work, but integrated the new, 190-foot tower into the church. It rises above the roof, immediately behind the portico, an arrangement that has since become commonplace.

I went inside the church, but a service was going on, so flash photography wasn't allowed. The church has a five-bay nave divided from the aisles by arcades of Corinthian columns. There are galleries over both aisles and at the west end. The nave ceiling is a flattened barrel vault, divided into panels by ribs. Until the creation of Trafalgar Square in the 1820s, Gibbs's church was crowded by other buildings, and it wasn't until most of them were removed that the design of the church, criticized widely at its construction, became more appreciated, famous, and copied widely.

|

Unlike comparable museums in continental Europe, the National Gallery was not formed by nationalizing an existing royal or princely art collection. It came into being when the British government bought 38 paintings from the heirs of John Julius Angerstein in 1824. After that initial purchase the Gallery was shaped mainly by its early directors and by private donations, which today account for two-thirds of the collection. The collection is small compared with many European national galleries, but encyclopedic in scope; most major developments in Western painting are represented with important works.

The present building, the third to house the National Gallery, was designed by William Wilkins from 1832 to 1838. Only the façade onto Trafalgar Square remains essentially unchanged from that time, as the building has been expanded piecemeal throughout its history. Wilkins's building was often criticized for the perceived weaknesses of its design and for its lack of space; the latter problem led to the establishment of the Tate Gallery for British art in 1897.

I did not go inside the museum right away, but wandered around Trafalgar Square first. But a bit later on, when the weather deteriorated, I did go inside (although, once again, most photography was prohibited).

|

|

When it began to rain lightly, I hightailed it back across the square to the National Gallery and went inside. I found a Victorian-appearing series of galleries and rather dim lighting, but, all in all, a very handsome building. I walked around admiring the paintings, mosaics, and other art for well over an hour before checking back at the entrance to see if it were dry enough for me to make my way back to the Chelsea.

|

Piccadilly now links directly to the theatres on Shaftesbury Avenue, as well as the major shopping and entertainment areas in the West End. Its status as a major traffic junction has made Piccadilly Circus a busy meeting place and a tourist attraction in its own right. The Circus is particularly known for its video display and neon signs mounted on the corner building on the northern side, as well as the Shaftesbury memorial fountain and statue, which is popularly, though mistakenly, believed to be of Eros. It is surrounded by several notable buildings, including the London Pavilion (you can spot it in my picture at left) and Criterion Theatre. Directly underneath the plaza is Piccadilly Circus Underground station, part of the London Underground system.

The "Piccadilly" name first appeared in 1626, because a house beloning to Robert Baker was located here- Baker being a tailor famous for selling piccadills (collars). The "Circus" part comes from the Latin word meaning "circle", because the intersection was originally a round open space at the street junction. (The junction ceased to circular in 1886 when Shaftesbury Avenue was built.) The junction is similar to Times Square both for the fact that it is at the center of the London Theatre district, and for the fact that the neon signs here are as dramatic as those in New York City.

The Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus was erected in 1893 to commemorate the philanthropic works of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. During the Second World War, the statue atop the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain was temporarily removed and was replaced by advertising billboards. It was returned in 1948.

From the Circus, I made my way back to the Chelsea. I have one more day I can devote to walking around London, and I hope the weather is better.

October 9

I did not get my wish for a really nice day to walk around town, but at least the weather was better than yesterday. At the front desk of the Chelsea, I found out that while it was supposed to be very cloudy all day long, there was no rain in the forecast. It was when I was asking these questions that I discovered that the hotel has umbrellas to loan to guests. But with a more positive forecast, I chose not to carry one around.

|

From the Millennium Hotel, I began by walking down Sloane Street to the southeast, and then I zig-zagged over to Victoria Street at Victoria Station. From there, I followed Victoria Street east and then northeast towards Parliament. Along the way I passed Westminster Abbey. I spent some time in the area near Parliament (and Big Ben) and also walked out onto Westminster Bridge to look up and down the Thames River.

Then I turned north to walk along Whitehall and passed the Prime Minister's residence at 10 Downing Street, the Cenotaph, and the headquarters of the Royal Horse Guards, eventually ending up again in Trafalgar Square. That was the first part of my walking tour today, and on the aerial view at right (which covers that part of the walk), I have marked the major landmarks that I saw and photographed. This aerial view may help you follow along with me as I have a look at a good many of London's iconic sites.

While the walk from the hotel to the foot of Victoria Street (about four blocks due south of Buckingham Palace) took maybe a half hour. I was walking slowly, admiring the architecture and having a look at every historical or building marker that I came across. It wasn't long, as I walked along Victoria Street towards the Houses of Parliament, that I came to one of these historical buildings- Westminster Abbey.

|

|

Since the coronation of William the Conqueror in 1066, all coronations of English and British monarchs have been in Westminster Abbey. There have been 16 royal weddings at the abbey since 1100. As the burial site of more than 3,300 persons, usually of predominant prominence in British history (including at least sixteen monarchs, eight Prime Ministers, poet laureates, actors, scientists, and military leaders, and the Unknown Warrior), Westminster Abbey is sometimes described as "Britain's Valhalla", after the iconic burial hall of Norse mythology.

Attached to the Abbey are a series of Cloisters, containing the crypts of these famous persons, although not the most well-known. In this somewhat gloomy area are Abbey persons working on brass rubbings and artwork, much of which is sold to support the Abbey itself, as any other Church. The Cloisters form a courtyard within the Abbey.

Westminster Abbey is one of the most hallowed sites in the entire British world. To those of us who live in a country scarcely 200 years old, it is hard to relate to institutions and buildings whose life span has been five times that. Just being close to the Abbey seemed to bring these feelings to life. One could almost imagine the voices of the rich and powerful, the rulers and would-be kings, and Churchmen and the people echoing down the corridors inside (where it was too dark for me to take non-flash photos). If the building itself could speak, if it could reveal all the hushed conversations, the shouts and the whispered importuning of those caught up in the sweep of events taking place there, what a treasure of knowledge and history it could disclose.

True, in this day and age, the Abbey has been commercialized to some extent, but there are still large areas where selling any merchandise is forbidden (and these areas comprise most of the complex), an there are even areas where speaking aloud is frowned upon. The quiet only enhances the feeling that one is not alone. Literally, that is, of course, quite true, as the bodies of many famous people in English history are buried beneath one's feet, or in vaults at one's side.

|

The church was founded by Benedictine monks, so that local people who lived in the area around the Abbey could worship separately at their own simpler parish church. In 1914, a former Rector of St Margaret's, referred to a mediaeval tradition that the church was as old as Westminster Abbey, owing its origins to the same royal saint, and that "The two churches, conventual and parochial, have stood side by side for more than eight centuries".

St Margaret's was rebuilt from beginning in 1486, at the instigation of King Henry VII, and the new church, which largely still stands today, was consecrated on 9 April 1523. It has been called "the last church in London decorated in the Catholic tradition before the Reformation". In the 1540s, the new church came near to demolition, when Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, planned to take it down to provide good-quality materials for his new palace in the Strand. He was only kept from carrying out his plan by the resistance of armed parishioners.

In 1614, St Margaret's became the parish church of the Palace of Westminster, when the Puritans of the seventeenth century, unhappy with the highly liturgical Abbey, chose to hold their Parliamentary services in a church they found more suitable: a practice that has continued since that time. The tower was rebuilt from 1734 to 1738, and the interior of the church came to its current appearance in 1877. By the 1970s, the number of people living nearby had dwindled, so services were moved to nearby parishes and the church brought under the authority of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey.

|

At right is a picture I took from Parliament Square Park, just north of St. Margaret's, of Big Ben and the entrance to the Houses of Parliament. This is probably the closest thing to a "picture postcard" shot of London that I achieved. The buses lend just the right color.

"Big Ben", of course, is the nickname for the Great Bell of the clock at the north end of the Palace of Westminster, and is usually extended to refer to both the clock and the clock tower. The official name of the tower in which Big Ben is located is (surprise, surprise) "the Clock Tower". The tower was designed in a neo-Gothic style, and, when completed in 1859, its clock was the largest and most accurate four-faced striking and chiming clock in the world. The tower stands 315 feet tall, and the climb from ground level to the belfry is 334 steps. Its base is square, measuring 39 feet on each side. The dials of the clock are 23 feet in diameter.

Big Ben is the largest of the tower's five bells and weighs 15 tons; until 1882 it was the largest bell in the United Kingdom. The origin of the bell's nickname is open to question; it may be named after Sir Benjamin Hall, who oversaw its installation, or heavyweight boxing champion Benjamin Caunt. Four quarter bells chime at 15, 30 and 45 minutes past the hour and just before Big Ben tolls on the hour. The clock uses its original Victorian mechanism, but an electric motor can be used as a backup.

The tower is a British cultural icon recognized all over the world. It is one of the most prominent symbols of the United Kingdom and parliamentary democracy, and it is often used in the establishing shot of films set in London.

|

(Picture at left) Looking further Eastward along Millbank Road at the Parliament buildings (correctly styled the "Palace of Westminster"). The Palace is done in a neo-Gothic design and was opened in 1852. The square tower at the southwest corner of the Palace is the Victoria Tower, the largest isolated Gothic tower in the world. At 323 feet, it is slightly taller than the more famous Clock Tower. It houses the Parliamentary Archives. If the Union Flag is flying, Parliament is sitting, and if the Royal Standard is flying, the Sovereign is present in the palace.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill (1874 – 1965) was a British statesman, army officer, and writer. He was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945, when he led Britain to victory in the Second World War, and again from 1951 to 1955. Churchill represented five constituencies during his career as a Member of Parliament (MP). Ideologically an economic liberal and imperialist, he began as a member of the Liberal Party (today's Labour Party), but for most of his career he was a member of the Conservative Party, which he led from 1940 to 1955.

|

Lambeth Palace has been the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury for nearly 800 years. Originally Lambeth Manor, the site was acquired by the archbishopric around 1200 AD and has the largest collection of records of the Church in its library. It has a large garden adjoining (which had an orchard until the early 1800s. The south bank of the Thames here developed slowly because the land was low and soggy (and called Lambeth Marsh); archbishops came and went by water, as did John Wycliff, who was tried here for heresy.

The great hall was completely ransacked by Cromwellian troops during the English Civil War. After the Restoration, it was completely rebuilt by archbishop William Juxon in 1663 with Gothic details. The palace remains one of London's most famous landmarks, and played a significant role in England's history.

|

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place of the House of Commons and the House of Lords- commonly known as the Houses of Parliament. Its name, which derives from the neighboring Westminster Abbey, may refer either to the Old Palace, a medieval building-complex destroyed by fire in 1834, or its replacement, the New Palace that stands today. The palace is owned by the monarch in right of the Crown and, for ceremonial purposes, retains its original status as a royal residence.

The first royal palace constructed on the site dated from the 11th century, and Westminster became the primary residence of the Kings of England until fire destroyed much of the complex in 1512. After that, it served as the home of the Parliament of England, which had met there since the 13th century, and also as the seat of the Royal Courts of Justice. In 1834 an even greater fire ravaged the heavily rebuilt Houses of Parliament, and few medieval structures survived.

The reconstruction was in the Gothic Revival style, and the remains of the Old Palace (except the detached Jewel Tower) were incorporated into its much larger replacement. The new palace has 1100+ rooms arranged symmetrically around two courtyards with a total floor area of 1.2 million square feet. The thousand-foot-long facade faces the Thames. Construction started in 1840 and lasted for 30 years, suffering great delays, cost overruns, and the deaths of both lead architects; interior work continued well into the 20th century. Major conservation work has taken place since then to reverse the effects of London's air pollution, and extensive repairs followed the Second World War, including the reconstruction of the Commons Chamber following its bombing in 1941.

|

|

Barry, two geologists, and a stonecarver toured Britain, looking at quarries and buildings, and finally selected Anston, a sand-colored magnesian limestone quarried in Anston, South Yorkshire. A crucial consideration in selecting Anston was transportation, achieved on water via the Chesterfield Canal, the North Sea, and the rivers Trent and Thames. Furthermore, Anston was cheaper, and could be supplied in blocks up to four feet thick that lent themselves to elaborate carving.

The stone soon began to decay due to pollution and the poor quality of some of the stone used. Although such defects were clear as early as 1849, nothing was done until 1928, when it was deemed necessary to use Clipsham stone, a honey-colored limestone from Rutland, to replace the decayed Anston. The project began in the 1930s but was halted by the outbreak of the Second World War, and completed only during the 1950s. By the 1960s pollution had again begun to take its toll, and discussions are ongoing about what to do next.

|

The Cenotaph is a war memorial, the origin of which is in a temporary structure erected for a peace parade following the end of the First World War that the British government planned to hold on Whitehall with soldiers marching down towards Parliament. The initial design for what would become the cenotaph was one of a number of temporary structures erected for this parade. Lloyd George had a design created for a "saluting point" for the parade.

The unveiling (described in The Times as a "quiet" and "unofficial" ceremony) took place on 18 July 1919, the day before the Victory Parade. Lutyens was not invited. During the parade, 15,000 soldiers and 1,500 officers marched past and saluted the Cenotaph, and it quickly captured the public imagination. Repatriation of the dead was not to happen, so the Cenotaph substituted for a tomb, attracting millions of people and a huge amount of flowers.

In the ensuing weeks, numerous public figures called for a permanent cenotaph to be constructed, and locations were discussed. Even though the middle of Whitehall seemed dangerous, the feeling was that the site had "been qualified by the salutes of Foch and the allied armies". The cabinet bowed to public pressure, approving the re-building in stone. Real wreaths were to be replaced with ones carved stone, although the flags would continue to be fabric. Construction began in May 1920 and was completed the next year. That is the Cenotaph that you see in my picture.

|

10 Downing Street is the headquarters of the Government of the United Kingdom and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, a post always held by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Number 10 is over 300 years old and contains approximately 100 rooms. A private residence occupies the third floor and the other floors contain offices and conference, reception, sitting and dining rooms where the Prime Minister works, and where government ministers, national leaders and foreign dignitaries are met and entertained. At the rear is an interior courtyard and a terrace overlooking a half-acre garden. Adjacent to St James's Park, Number 10 is near Buckingham Palace, the London residence of the British monarch, and the Palace of Westminster, the meeting place of both houses of parliament.

Originally three houses, Number 10 was offered to Sir Robert Walpole by King George II in 1732. Walpole accepted on the condition that the gift was to the office of First Lord of the Treasury rather than to him personally. Walpole commissioned the joining of the houses. But despite its size and convenient location near to Parliament, few early Prime Ministers lived there. Costly to maintain, neglected, and run-down, Number 10 was close to being demolished several times but the property survived and became linked with many statesmen and events in British history.

What impressed me was the (apparent) lack of security; compare the scene here to the White House- only one guard here, and I couldn't see that he was armed. It all seemed very low-key, although it may have been true that no one of importance was inside at the time I walked by. There seems to be a continual small crowd gathered across the street to watch the comings and goings. Some are tourists, to be sure, but there seemed to be, also, regular Londoners just there in hopes of getting a glimpse of Harold or Reggie or whomever.

A bit further up Whitehall is the headquarters of the Horse Guards- the splendidly accoutered sentries of the Household Cavalry. The historic building was built in the mid-18th century, replacing an earlier building, as a barracks and stables for the Household Cavalry, later becoming an important military headquarters. Horse Guards originally formed the entrance to the Palace of Whitehall and later St James's Palace; for that reason it is still ceremonially defended by the Queen's Life Guard. Although still in military use, part of the building houses the Household Cavalry Museum which is open to the public.

Every hour or so there is a guard ceremony like this one, although this is not the same as the changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace. |

Later that day, these are the Household Cavalry returning from the changing of the Guard ceremony at the Palace. They come back to the Headquarters of the Horse Guards seen earlier, by a road that runs along St. James' Park. |

So I continued up Whitehall past the Horse Guards parade ground (hidden from view behind the buildings on my left along Whitehall) towards Trafalgar Square.

|

|

|

So my walk today will continue past Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The weather has definitely cooperated, and while there are lots of clouds still around, I can see blue sky occasionally. My goal in the second part of my walk this Sunday will be St. Paul's Cathedral.

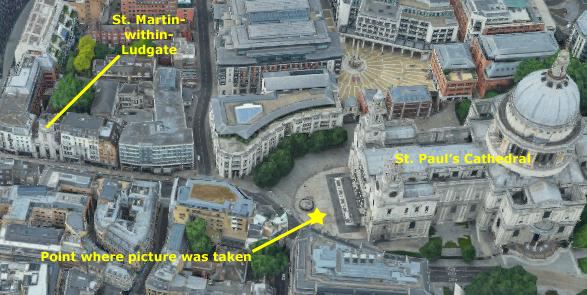

|

At right is an aerial view of the part of London that I covered in this second part of my walk, and on that aerial view I have marked the locations of many of the stops I made and structures that I photographed. The aerial view is about a mile and a half wide (just so you get an idea of the scale).

As I came up The Strand, I could see St. Mary-le-Strand in the middle of the road, and when I got close to it, I turned and went down to Waterloo Bridge to get some views looking back down the Thames. Back on The Strand, I passed the Royal Courts of Justice, a number of London's oldest pubs and dining clubs. Off the street was the Temple Church.

The street changed to Fleet Street at the Temple Bar Memorial, and passed the old Bank of England building, I again left the street to investigate some of the older buildings between Fleet Street and the Thames- getting a look at one church build next to a crumbling portion of an old section of the London wall. I ended up, as I planned, at St. Paul's Cathedral, and took a number of pictures in the area around it before going inside to have a look at the interior. So come on along and I'll try to show you what I was able to see this afternoon.

|

|

The church is the second to have been called St Mary le Strand, the first having been situated a short distance to the south. That church was pulled down in 1549 by Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset to make way for Somerset House. The parishioners were promised a new church but never got it, until the early 1700s when the "Commission for Building Fifty New Churches" was set up. Construction began in February 1714, and the steeple was completed in September 1717. But the church was not consecrated for use until 1723. Bonnie Prince Charlie is alleged to have renounced his Roman Catholic faith in the church to become an Anglican during a secret visit to London in 1750. The parents of Charles Dickens were married here in 1809.

At the start of the 20th century the London County Council proposed to demolish the church to widen the Strand; a public campaign suceeded in averting this, although the graveyard was obliterated and the graves moved. The London Blitz of the Second World War caused much damage to the surrounding area but again the church avoided destruction, though it did suffer damage from a nearby bomb explosion.

|

|

The obelisk was originally erected in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis on the orders of Thutmose III, around 1450 BC, and he had a single column of text carved on each face. Other inscriptions were added about 200 years later by Rameses II to commemorate his military victories. The obelisks were moved to Alexandria by Augustus in 12 BC and set up in the Caesareum– a temple built in honor of either Mark Antony or Julius Caesar – but were toppled some time later. This had the fortuitous effect of burying their faces and so preserving most of the hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering. On erection of the obelisk in 1878, a time capsule was concealed in the front part of the pedestal. Items inside included a set of 12 photographs of the best-looking English women of the day, a box of cigars, a set of imperial weights, a baby's bottle, some children's toys, a complete set of contemporary British coins, a portrait of Queen Victoria, several Bibles, a Bradshaw Railway Guide, a map of London and copies of 10 daily newspapers.

|

The courts within the building are generally open to the public with some access restrictions depending upon the nature of the cases being heard. Those in court who do not have legal representation may receive some assistance within the building. A Citizens Advice Bureau is based in the Main Hall which provides free, confidential and impartial advice by appointment to litigants-in-person. There is also an office of the Personal Support Unit where litigants-in-person can receive emotional support and practical information about court proceedings.

In 1868 the winner of a design competition began working on the structure, and construction started in 1873, and was officially opened by Queen Victoria in 1882. Parliament paid £1.5 million for the 6-acre site upon which 450 houses had to be demolished. The building cost £700,000 to build and interior work another £1 million. The building is 470 feet wide and 460 feet deep and 245 feet high. Entering through the main gates on the Strand, one passes under two elaborately carved porches fitted with iron gates. The carving over the outer porch consists of heads of the most eminent judges and lawyers. Over the highest point of the upper arch is a figure of Jesus; to the left and right at a lower level are figures of Solomon and Alfred the Great; that of Moses is at the northern front of the building. Also at the northern front, over the Judges entrance are a stone cat and dog representing fighting litigants in court.

On the other side of the Strand, extending down into Fleet Street, were many of London's oldest (and most exclusive) pubs and dining clubs, but only four or five of them still remain.

The George |

(Picture at left) Some of these pubs are quite old and relatively famous, including the one shown here, the George, in which a great many literary figures, including Charles Dickens, are said to have spent a great deal of time.

(Picture at right)

|

The Wig and Pen |

A bit past the Royal Courts of Justice, I came to yet another monument/building right in the middle of the street. (This is about the fourth of fifth such instance of something being in the middle of a street or road, so I assume that's pretty common around here.)

|

|

The term Temple Bar strictly refers to a notional bar or barrier across the route, but is commonly used to refer to the 17th-century ornamental Baroque arched gateway designed by Christopher Wren which spanned the road until its removal in 1878; a memorial pedestal topped by a dragon symbol of London, and containing an image of Queen Victoria was erected to mark the bar's location in 1880. Wren's arch was preserved and there are plans to re-erect it somewhere in the City.

The elaborate pedestal in a Neo-Renaissance style serves as the base for a sculpture by Charles Bell Birch commonly called the Griffin (in fact a dragon), in reference to the heraldic crest of the Corporation of the City of London. The pedestal is decorated with statues by Joseph Boehm of Queen Victoria and her son The Prince of Wales, the last royals to have entered the City through Wren's gate, which event is depicted in one of the reliefs which also decorate the structure.

|

The Temple Church is located between Fleet Street and the River Thames and was built by the Knights Templar as their English headquarters. It was consecrated in 1185 by Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem. During the reign of King John (1199–1216) it served as the royal treasury, supported by the role of the Knights Templars as proto-international bankers. It is jointly owned by the Inner Temple and Middle Temple Inns of Court, bases of the English legal profession. It is famous for being a round church, a common design feature for Knights Templar churches, and for its 13th- and 14th-century stone effigies. It was heavily damaged by German bombing during World War II and has since been greatly restored and rebuilt.

The church building comprises two separate sections: the original circular church building, called the Round Church and now acting as a nave, and a later rectangular section adjoining on the east side, built approximately half a century later, forming the chancel.

I continued walking generally eastward on both sides of Fleet Street and on into The City- the original area of London. I was really just following my nose, and found myself crossing Farringdon Street where Fleet Street changes into Ludgate Hill. Then I came to a street called Old Bailey, and I thought this might lead me to the building of the same name, so I turned north for a block or two and found it on my right.

|

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales (commonly called the Old Bailey, after the street on which it stands) is a court in London and one of a number of buildings housing the Crown Court. Part of the present building stands on the site of the medieval Newgate gaol, on a road named Old Bailey that follows the line of the City of London's fortified wall (or bailey), which runs from Ludgate Hill to the junction of Newgate Street and Holborn Viaduct. The Old Bailey has been housed in several structures near this location since the sixteenth century. The Crown Court sitting at the Central Criminal Court deals with major criminal cases from within Greater London and in exceptional cases, from other parts of England and Wales. Trials at the Old Bailey, as at other courts, are open to the public; however, they are subject to stringent security procedures.

The original medieval court was first mentioned in 1585; it was next to the older Newgate Prison. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and rebuilt in 1674, with the court open to the weather to prevent the spread of disease. In 1734, it was refronted, enclosing the court (which lead to outbreaks of typhus). It was rebuilt again in 1774 and a second courtroom was added in 1824. In 1834, it was renamed as the Central Criminal Court and its jurisdiction extended to the whole of the English jurisdiction for trials of major cases. Hangings were a public spectacle in the street outside until May 1868.

The present Old Bailey building dates from 1902 but was officially opened in 1907; it was built on the site of the infamous Newgate Prison, which was demolished to allow the court buildings to be constructed. On the dome above the court stands a bronze statue of Lady Justice; she holds a sword in her right hand and the scales of justice in her left. During the Blitz of World War II, the Old Bailey was bombed and severely damaged, but subsequent reconstruction work restored most of it in the early 1950s.

|

The steeple, standing about 160 feet tall, was finished in 1704; it has three diminishing storeys, square in plan, the middle one with a freestanding Ionic colonnade. The church functioned as an important center of City of London society and music. Local residents and students from the nearby Christ's Hospital school (including the young Samuel Coleridge) attended services in great numbers. But the school moved out of The City, and the congregation dwindled as businesses moved into the area and residents moved to more suburban areas. By April 1937, the membership had dropped to 77.

The church was severely damaged in the Blitz on 29 December 1940 when a firebomb struck the roof and tore into the nave. Much of the surrounding neighbourhood was also set alight— a total of eight Wren churches burned that night. At Christ Church, only the tower and four main walls, made of stone, remained standing. Authorities decided not to rebuild the church; the ruins have been left standing (although stabilized), and the site is now a public garden.

|

The present cathedral, dating from the late 17th century, was designed in the English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. Its construction, completed in Wren's lifetime, was part of a major rebuilding programme in the City after the Great Fire of London.

The cathedral is one of the most famous and most recognisable sights of London and is a working church with hourly prayer and daily services. Its dome, framed by the spires of Wren's City churches, has dominated the skyline for over 300 years. At 365 feet high, it was the tallest building in London from 1710 to 1967. The dome is among the highest in the world. St Paul's is the second-largest church building in area in the United Kingdom after Liverpool Cathedral.

Services held at St Paul's have included the funerals of Admiral Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, and Sir Winston Churchill; jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria; peace services marking the end of the First and Second World Wars; the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer; the launch of the Festival of Britain; and the thanksgiving services for jubilees and birthdays of Queen Elizabeth II.

Counting the pre-Normal churches, there have been five "St. Paul's" on this site. The fourth St Paul's, generally referred to as Old St Paul's, was begun by the Normans after the 1087 fire. A further fire in 1136 disrupted the work, and the new cathedral was not consecrated until 1240. During the period of construction, the style of architecture had changed from Romanesque to Gothic and this was reflected in the pointed arches and larger windows of the upper parts and East End of the building. The Gothic ribbed vault was constructed of wood rather than stone, which affected the ultimate fate of the building.

|

On 12 September 1940 a time-delayed bomb that had struck the cathedral was successfully defused and removed by a bomb disposal detachment of Royal Engineers under the command of Temporary Lieutenant Robert Davies. Had this bomb detonated, it would have totally destroyed the cathedral; it left a 100-foot crater when later remotely detonated in a secure location. As a result of this action, Davies and Sapper George Cameron Wylie were each awarded the George Cross. Davies' George Cross and other medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum, London.

|

| "Wreathed in billowing smoke, amidst the chaos and destruction of war, the pale dome stands proud and glorious—indomitable. At the height of that air-raid, Sir Winston Churchill telephoned the Guildhall to insist that all fire-fighting resources be directed at St Paul's. The cathedral must be saved, he said, damage to the fabric would sap the morale of the country." |

It is hard for someone from the United States, such as myself, to really understand the psyche of a nation as old as most of those in Europe. Here we have a cathedral, that was completed and consecrated in 1697, surviving, some 250 years later, a bombing with weapons that could not even have been imagined at the time it began its service. Something that old and that iconic becomes part of the fabric of a society. I might note that one of the cathedral's most iconic moments was still ahead- only four years after my visit. It would be in St. Paul's that the royal wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana would be held in 1981.

|

|

St Martin, Ludgate, is an Anglican church that was one of the churches rebuilt after the Great Fire by Sir Christopher Wren; the rebuilding was completed in 1684. But the history of the church vastly predates the fire; some legends connect the church with the legendary King Cadwallo, and a sign on the front of the church (which I passed on my way back to the Chelsea) reads "Cadwallo King of the Britons is said to have been buried here in 677". The earliest written record of a church here dates to 1174, and we know that a Blackfriars monastery was built nearby in 1278. The church was rebuilt in 1437 and the tower was struck by lightning in 1561. The parish books start from 1410. Before the Reformation, the church was under the control of Westminster Abbey, and afterwards under St. Paul's Cathedral. I am continually struck that so many buildings in London have similar stories to tell.

This was the one church I planned on going inside, and it was, to put it mildly, spectacular. In my travels up until now, I think it is the most beautiful church of any kind that I have been in (although in future years, I can say, I will have the opportunity to visit churches that are even grander and more ornate).

|

(Picture at left) The inside of St. Paul's Cathedral is breathtaking, probably the most beautiful church I have seen, including the Abbey itself. Of course, the Abbey is considerably older and more Gothic. The inside of the Cathedral is very large, and the stained-glass windows lend a surreal effect. It was somewhat dark, so I had to be very careful with the camera.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Leaving the cathedral, I made my way back to the Chelsea Hotel to begin my usual preparations for the class I would be conducting over the next week. I found London to be an amazing place, and, obviously, one could spend many weeks here and still not get thoroughly immersed in the history of the city; I am sure that a "church tour" by itself could take a week or more. But I am looking forward to this coming weekend, when I plan on heading out of the city to experience the English countryside.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

Return to the Index Map for My Trip to England |