|

November 24-29: A Class in Amsterdam, Netherlands |

|

September 7-10: A Vacation in Palm Springs |

|

Return to Index for 1980 |

One of the clients that I did a lot of classes for was Merck, which is actually a division of a large international company- Merck, Sharp and Dohme. One of their major offices is in Amsterdam; they have their warehouse operation there for all of Europe. As it turned out, they wanted to have a SSAD class there in November, so they arranged with IST for me to come teach it. Since the week before was open for me, I decided to spend a few days in Paris and environs before the class.

Traveling to Paris

|

This picture of my aircraft waiting at the gate at O'Hare will seem odd to modern eyes, as there are very few airports today that still board planes with ramps that roll up to the side; jetways are the order of the day now. I took this picture as I was walking across the tarmac from the terminal.

It may look as if I am heading for the first-class boarding ramp, but in actuality clients rarely pay for first-class travel overseas (although some do within the United States). So I was in coach, but on the 747 that isn't bad at all.

The flight was uneventful, although I must admit that I don't like flying all night and arriving someplace early in the morning, since I have a hard time getting any sleep in an airplane seat (first class or not). But the airlines set it up that way for two reasons. First, travelers arrive in Europe in the early morning, and thus have a full day for either their business or their tourist activities. Second, if the traveler has to connect to another onward flight, they will have plenty of time to get to their final destination and still have the better part of a day left to work with.

Going in the opposite direction, it really doesn't matter much; most flights leave Europe for the States in mid-morning; counting both the air travel time and the time differential, they will still get to the States in the early afternoon- again plenty of time to get to hotels or take onward flights to destinations further west. Hence, only one day is taken up with travel.

|

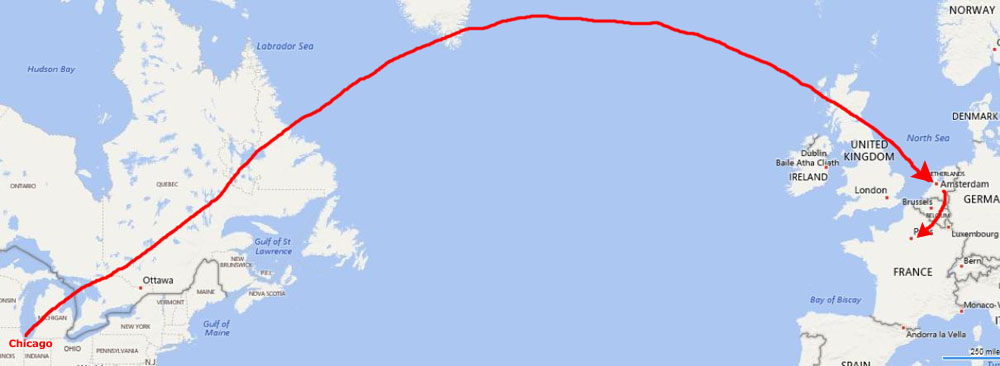

I guess I am being overly precise with the flight map above, but the flights from Chicago to Europe don't fly over what you might think they might. The shortest distance to Europe takes flights way north over Greenland before they come south again to London, Amsterdam, Paris, or other European cities. "It's the curvature, dummy!" might be the navigator's motto. Because the airline was KLM, they stopped in Amsterdam, where I changed to a smaller plane for the flight to Paris. (I could have flown direct on Air France, but the fare would have been significantly more, considering I was also going to Amsterdam.)

Here's the Netherlands, one of earth's flattest countries, as we are coming into Schipol airport just outside Amsterdam. Much of the Netherlands is land reclaimed from the Atlantic. |

Here is the terminal at Schipol. I was to come to find that this early morning haze is very common in the Low Countries. |

After changing planes and going through two terminals at Amsterdam, I got on a smaller KLM plane and went onward to Paris.

|

|

The planning and construction phase of what was known then as Aéroport de Paris Nord (Paris North Airport) began in 1966. On 8 March 1974 the airport, renamed Charles de Gaulle Airport, opened. Terminal 1 was built in an avant-garde design of a ten-floors-high circular building surrounded by seven satellite buildings, each with six gates allowing sunlight to enter through apertures. The main architect was Paul Andreu, who was also in charge of the extensions during the following decades.

Not knowing much about ground transportation to and from the airport, I just got a taxi and gave them the address of the hotel that Steve had found for me.

A Bit of Orientation

|

But I visited two locations outside Paris as well. The Palace at Versailles, one of the iconic locations in all of France, is actually pretty close-in, now, although it was once a distance out into the countryside. Residence of Kings and Queens, the palace and its world-famous gardens is now in the southwest area of the city. It was a short train ride from center city.

A longer trip was my day excursion out to Rheims, a famous French city some 70 miles northeast of the center of Paris. I wanted to see the famous cathedral there, and some of the other sights of that old city, and I spent all day on that excursion.

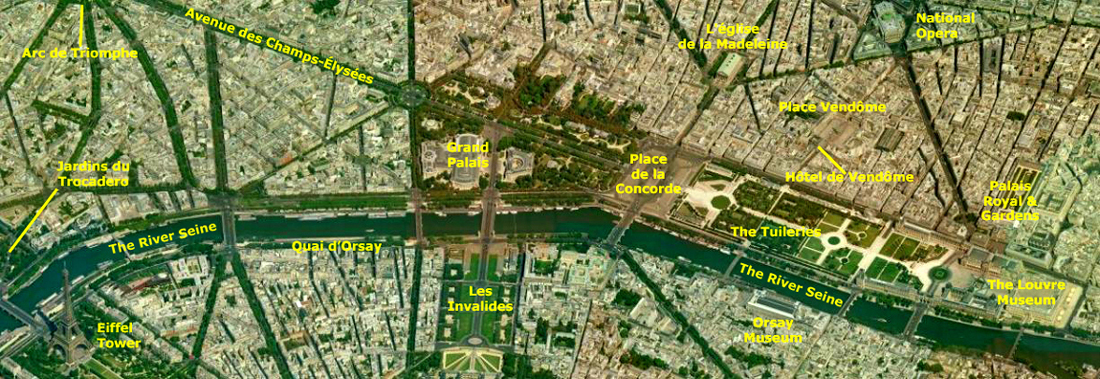

Most of my time was spent in the center of Paris, in a huge rectangle bounded by the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, and Montmartre. Here is an aerial view of that area (well, the Arch is just outside the view to the northwest), and you will easily be able to see that my hotel was extremely well-located for the places that I wanted to see and the things I wanted to do:

|

It will be very convenient to organize my pictures around Versailles, Rheims, and Paris, and, within the city, around the major sights that I visited. The order in which I did things is quite unimportant; knowing that order will add precious little to the amazing beauty of almost everything I saw.

| NOTE: In visiting Versailles, Rheims, and, of course, Paris, I took quite a few pictures- too many, really, to put on a single album page. So I am going to divide this visit to France into three pages. First, we'll take a look at Paris itself, then Versailles, then Rheims. So, at the bottom of this page devoted to the sights and activities in Paris, there will be an onward link to the page for Versailles, and from that page there will be a link to the page for Versailles. To get to other pages in the photo album as a whole, return to the top of this page or use the link at the bottom of the Rheims page. |

The Hôtel de Vendôme and Place Vendôme

As I was on my own time and money, I asked Steve to avoid the large hotels in Paris, the ones that are also quite expensive, and put me in someplace reasonable but clean and neat. In fact, he put me in the Hotel Place Vendôme.

|

|

The Hotel Vendôme was built in 1723 by Pierre Perrin, the secretary of the Roi Soleil; it has always been a "luxury", "boutique" hotel, but eclipsed in size and fame buy other hotels- chains and independents. The hotel was modern but original, and did not feel like a "cookie-cutter" property; the decor was refined and done in elegant colors. The hotel was small, with some 30 rooms, each of which was unique.

The square and the Hotel Vendôme were certainly centrally-located in Paris; I could walk anywhere, just about. The particular few blocks I was in were, it seemed, business-oriented; IBM had their major Paris office in the same complex that the hotel was in.

|

The site of the square was formerly the hôtel (city residence and gardens) of César, duc de Vendôme. The plot was purchased by the King, and actual identical facades constructed around the square, behind which lot buyers would then build their homes or businesses. When state finances ran low, the financier John Law took on the project, built himself a residence behind one of the façades, and the square was complete by 1720, just as his paper-money Mississippi bubble burst. Law suffered a major blow when he was forced to pay back taxes amounting to some tens of millions of dollars. To raise the money, he sold his his property to members of the exiled Bourbon-Condé family who later returned their land in the town of Vendôme. Between 1720 and 1797, they acquired much of the square, and gave it the name it has today.

Being so close to the hotel, I walked through this area at least a bit on each day I was here, and took pictures of some of the architecture that caught my eye. On the day I went to the Arch de Triomphe, I went south from by hotel to the Rue de Rivoli and then west to the Place de la Concorde; this is where the Champs-Élysées begins.

|

The Place de la Concorde, at over 20 acres, is the largest square in the French capital, and is at the eastern end of the Champs-Élysées. At each of the eight angles of the octagonal Place is a statue, representing a French city- Brest, Rouen, Lyon, Marseille, Bordeaux, Nantes, Lille (seen in my photo) and Strasbourg.

The place was designed in 1755 as a moat-skirted octagon between the Champs-Elysées to the west and the Tuileries Garden to the east. Decorated with statues and fountains, the area was named Place Louis XV to honor the king at that time. The square showcased an equestrian statue of the king, which had been commissioned in 1748 by the city of Paris. The structures across Rue de Rivoli to the north (separated by Rue Royale) two magnificent identical stone buildings were constructed; these structures remain among the best examples of Louis Quinze style architecture in the city, and you can see them at the left side of my picture.

During the French Revolution the place had a darker history. The statue of Louis XV of France was torn down and the area renamed Place de la Révolution; it was the site of the guillotine used to execute King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, Princess Élisabeth of France, Charlotte Corday, Madame du Barry, Georges Danton, Antoine Lavoisier and Robespierre. In 1795, under the Directory, the square was renamed Place de la Concorde as a gesture of reconciliation after the turmoil of the French Revolution. After the Bourbon Restoration of 1814, the name was changed back to Place Louis XV, and in 1826 the square was renamed Place Louis XVI. After the July Revolution of 1830 the name was returned to Place de la Concorde and has remained that way since.

|

The site of this edifice, centered at the end of rue Royale, had originally contained a synagogue, but it was seized from the Jews of Paris in 1182, and consecrated to a church dedicated to Mary Magdalene. Two false starts were made in building a church on this site. Construction of the first design, commissioned in 1757, was halted in 1764. After the designer's death, a new design, based on the Roman Pantheon, was approved and construction began. At the start of the Revolution of 1789, however, only the foundations and the grand portico had been finished; work was discontinued while debate simmered as to what purpose the eventual building might serve in Revolutionary France.

In 1806 Napoleon made his decision to erect a commemorative memorial- the "Temple de la Gloire de la Grande Armée"- on the site. The then-existing foundations were razed, preserving the standing columns, and work begun anew. But with completion of the Arc de Triomphe in 1808, the original commemorative role fwas reduced. After the fall of Napoleon, King Louis XVIII determined that the structure would be used as a church, dedicated to Mary Magdalene, and construction began again on the neo-classical structure. The nave was vaulted in 1831 and the building was finally consecrated as a church in 1842.

On another day, I walked northeast of Place Vendôme and came by a beautiful building- the Palais Garnier, a 1,979-seat opera house, which was built from 1861 to 1875 for the Paris Opera. It was called the Salle des Capucines, because of its location on the Boulevard des Capucines, but soon became known as the Palais Garnier, in recognition of its opulence and its architect, Charles Garnier. The theatre is also often referred to as the Opéra Garnier and historically was known as the Opéra de Paris or simply the Opéra, as it is the primary home of the Paris Opera and its associated Paris Opera Ballet.

The Palais Garnier sits in the middle of a large square, and is always very busy. It is getting late in the day, but there may have been a production going on to account for the lights. |

I am impressed by the grace and majesty of many of the large public buildings in Paris, and many of the smaller ones as well. I think what is interesting about them is that they are simply so old. |

The Palais Garnier has been called "probably the most famous opera house in the world; this is at least partly due to its use as the setting for Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera. But as I said above, what is striking to me, as an American who has always lived in the part of my country mostly built since the Second World War, it the age of the structure and its ornateness. Buildings in my experience are always relatively new and, save for churches, more utilitarian than artistic.

|

During the Paris Commune in 1871, the painter Gustave Courbet proposed that the column be disassembled and preserved at the Hôtel des Invalides. His thinking was that it was inappropriate that a monument to war should stand on an avenue named for peace. His project as proposed was not adopted, though in 1871 legislation was passed authorizing the dismantling of the imperial symbol. When the column was taken down that year its bronze plates were preserved. After the suppression of the Paris Commune by Adolphe Thiers, the decision was made to rebuild the column with the statue of Napoléon restored at its apex.

In 1874, the column was re-erected at the center of Place Vendôme with a copy of the original statue on top. An inner staircase leading to the top is no longer open to the public.

The Champs-Élysées and the Arch de Triomphe

|

In the middle of the gardem is the Élysée Palace, the official residence of the Presidents of France, but it is not on the Avenue itself. The Champs-Élysées ends at the Arc de Triomphe, built to honor the victories of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The first one-third mile of my walk up to the Arc de Triomphe was through a park, and I could see the Élysée Palace on my left. Then the park ended, and for the rest of my walk I was on a typical city street- but not so typical for all the high-end stores and restaurants that I passed. I should mention, however, that among all these upscale shops I passed both a McDonalds and a Burger King. The French do love exotic foreign cuisine.

|

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile ("Triumphal Arch of the Star") is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the center of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Place de l'Étoile — the étoile or "star" of the juncture formed by its twelve radiating avenues.

The Arc de Triomphe honours those who fought and died for France in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, with the names of all French victories and generals inscribed on its inner and outer surfaces. Beneath its vault lies the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I.

The Arc de Triomphe was designed by Jean Chalgrin in 1806 to be the central cohesive element of the Axe historique (historic axis, a sequence of monuments and grand thoroughfares on a route running northwest from the courtyard of the Louvre). Another Arch is planned to anchor the northwest end of the Avenue; it will be called the Grande Arche de la Défense. Iconography on the arch pits heroically nude French youths against bearded Germanic warriors in chain mail. It set the tone for public monuments with triumphant patriotic messages.

Inspired by the Roman Arch of Titus, the Arc de Triomphe is 165 feet high, 150 feet wide and 75 feet thick. The central vault (opening) is 95 feet high and 50 feet wide. There are also smaller transverse vaults. (Three weeks after the victory parade in 1919, marking the end of hostilities in World War I, Charles Godefroy flew a biplane under the arch's primary vault, with the event captured on newsreel. This arch was the tallest triumphal arch in the world until the completion of the Monumento a la Revolución in Mexico City in 1938; it is about 220 feet high.

|

The Arc de Triomphe is located at the centre of a dodecagonal configuration of twelve radiating avenues. It was commissioned in 1806 by Emperor Napoleon after the victory at Austerlitz; this was the peak of his fortunes. Laying the foundations alone took two years and, in 1810, when Napoleon entered Paris from the west with his bride Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, he had a wooden mock-up of the completed arch constructed. During the Bourbon Restoration, construction was halted and it would not be completed until the reign of King Louis-Philippe, between 1833 and 1836.

Following its construction, the Arc de Triomphe became the rallying point of French troops parading after successful military campaigns and for the annual Bastille Day Military Parade. Famous victory marches around or under the Arch have included the Germans in 1871, the French in 1919, the Germans in 1940, and the French and Allies in 1944 and 1945. After the interment of the Unknown Soldier, however, all military parades have avoided marching through the actual arch. The route taken is up to the arch and then around its side, out of respect for the tomb and its symbolism. Both Hitler in 1940 and de Gaulle in 1944 observed this custom. The Arch had to be thoroughly cleaned (through bleaching) in the late 1960s; it had grown quite blackened from soot and automobile exhausts.

|

The first view I captured on film was this view of the Champs-Élysées looking back along the way I have come. The easiest location to pick out in this particular view is, of course, the Place Vendôme; you can easily see the Vendôme Column, and so you know that the square and my hotel are at its base. The Champs-Élysées itself stretches away to the southeast, and in the distance you can see the gardens of the Tuileries and the Place de la Concorde.

In the nearground, look at how wide the Champs-Élysées is. Not only is the avenue itself wide, but the sidewalk is as wide as most streets in New York. The Place Vendôme is about a mile and a half from here, and that will give you some scale. The Champs-Élysées is just like you may have heard of it; it is very similar to Michigan Avenue, Fifth Avenue, or any other very upper-class street in any major city. It is usually thronged with people, who shop in the exclusive stores along the street.

The Parisians are upset about one thing (actually, they are upset about a great many things involving Americans) involving this street. McDonalds came to Paris years ago and opened a franchise right on the Champs-Élysées (I can only imagine that the property owner who sold his property to them or rents the ground floor of his building to them has gotten a lot of grief). The Parisians think that it denigrates the street to have fast food outlets there, but then again there are two or three on Michigan Avenue and more than one on Fifth Avenue. They're everywhere, they're everywhere!

I will freely admit that on my walk up here, I stopped in the McDonalds for some french fries (just to say that I had french fries in France). One might have thought that the only other customers would have been kids who are less invested in keeping France French, but the restaurant, which was absolutely packed with people, had young and old, well-dressed and not so stylish. So it seems that while the Academie Francaise might which that Americanisms could be controlled, this is one that is pretty much out-of-control.

One of the very interesting things about coming to Europe was that I was able to see for my own eyes all the famous landmarks that I had so often seen pictures of, and this was certainly no exception. The French certainly keep everything clean and neat; the Arch was certainly in excellent shape. The Arc de Triomphe sits in the middle of a traffic circle; Paris (and Europe in general) use this traffic control structure frequently, and so if you are going to drive in Europe, you'd better get familiar with the "rules of the road" for them. Here are some pictures that were taken at the top of the arch:

This looks northeast. You can see the Basilica Sacre Coeur on top of the hill in the distance. There are twelve "spokes" of major Paris streets that converge here. |

Here we are looking off to the southeast, across the River Seine, to the Eiffel Tower. The day was getting late and the weather was becoming overcast. |

This view looks northwest as beyond the Arc de Triomphe the Champs-Élysées changes to the Avenue de la Grande Armée. Most of the taller buildings in Paris are in the core you see here. |

I wish the weather had been nicer, but I prevailed upon another tourist to take this picture of me on top of the Arc de Triomphe, with the Eiffel Tower in the background. |

Paris is similar to Washington, DC, in that there seems to be an unwritten rule that no building be taller than the city's iconic structure (the Washington Monument in our own capital and the Eiffel Tower here). Here, that rule only seems to apply to the area within a mile or so of the Eiffel tower, as there are taller buildings in the city core as well as in Montmartre to the southeast. For a city as old as Paris, the main streets are remarkably symmetrical, although once you get off those primary avenues, the smaller ones can be quite confusing.

At the Louvre Museum

|

The museum is housed in the Louvre Palace, originally built as a fortress in the late 12th century under Philip II. Remnants of the fortress are visible in the basement of the museum. Due to the urban expansion of the city, the fortress eventually lost its defensive function and, in 1546, was converted by Francis I into the main residence of the French Kings. The building was extended many times to form the present Louvre Palace.

In 1682, Louis XIV chose the Palace of Versailles for his household, leaving the Louvre primarily as a place to display the royal collection, including, from 1692, a collection of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. In 1692, the building was occupied by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which in 1699 held the first of a series of salons. The Académie remained at the Louvre for 100 years. During the French Revolution, the National Assembly decreed that the Louvre should be used as a museum to display the nation's masterpieces.

The Louvre: Southeast Entrance |

By 1874, the Louvre Palace had achieved its present form of an almost rectangular structure with the Sully Wing to the east containing the Cour Carrée (Square Court) and the oldest parts of the Louvre; and two wings which wrap the Cour Napoléon, the Richelieu Wing to the north and the Denon Wing, which borders the Seine to the south.

The Louvre is involved in controversies that surround cultural property seized under Napoleon I, as well as during World War II by the Nazis. During Nazi occupation, thousands of artworks were stolen. But after the war, 61,233 articles of more than 150,000 seized artworks returned to France and were assigned to the Louvre's Office des Biens Privés. In 1949, it entrusted 2,130 unclaimed pieces (including 1,001 paintings) to the Direction des Musées de France in order to keep them under appropriate conditions of conservation until their restitution. Until the identification of their rightful owners, which declined at the end of the 1960s, they are registered indefinitely on separate inventories from the museum's collections.

Just inside the entrance is this first hall, with cases containing jewelry and gold items. |

I did not write down the name of the specific painting, but this shot gives you a good impression as to what the interior of the museum looks like. |

The Louvre is enormous; one can't possibly hope to see everything in it in even a few days. All I could do was hit the high points, and go to the galleries that would contain things I was interested in. Now I know what my Davidson professor in Humanities meant when he said that as part of his education he spent an entire year in Paris, and most of that in the Louvre.

|

|

There were many, many works, large and small, that it would be nice to have photographed, but after a while you have to ask yourself what the point of that would be, since there are pictures of all the museum's works in one book or another. But I did take a photo of one work that caught my eye- perhaps because I happened to see a sole individual standing in front of it.

From the plaque next to the work, I learned it is entitle The Wedding Feast at Cana, painted in 1563 by Paolo Veronese. Like many works, it depicts a Biblical story- this one of a wedding banquet at which Jesus converts water to wine (John 2:1–11). The 20-foot by 30-foot work was executed in the Mannerist style of the High Renaissance (1490–1527); at some 600 square feet, it is the museum's largest painting.

I enjoyed the couple of hours I spent here in the Louvre immensely; I saw a good many works that I'd seen pictures of before, or had occasion to study in college. Perhaps there is a book somewhere with photos of the museum's entire collection; it would be fun to be able to peruse it from an armchair, but then nothing much compares to seeing the actual work.

Sacré-Cœur Basilica

|

|

There are apartments and businesses right up to the gates to the church grounds. It was quite chilly on this day, and I recall stopping in a little cafe to get some hot chocolate and warm myself up. When I packed for Europe, I didn't think to bring a very heavy coat. This view looks at the church from across the street in front of it, which is about a block away from Boulevard St. Denis (one of the main thoroughfares in Paris), and shows the gates to the church grounds and the steps leading up to the Cathedral.

The inspiration for Sacré Cœur's design originated in 1870, on the day of the proclamation of the Third Republic, with a speech by Bishop Fournier attributing the defeat of French troops during the Franco-Prussian War to a divine punishment after "a century of moral decline" since the French Revolution. He referred to the division in French society that arose between devout Catholics and legitimist royalists on one side, and democrats, secularists, socialists and radicals on the other.

|

The land at the summit of Montmartre was seized from its owners (in a process similar to eminent domain), and Architect Paul Abadie won the competition to design the basilica. With delays in assembling the property, the foundation stone was finally laid in 1875. Passionate debates concerning the Basilica were raised in the Conseil Municipal in 1880, where the Basilica was called "an incessant provocation to civil war" and attempts were made to rescind the law of 1873. The matter reached the Chamber of Deputies in the summer of 1882; the Basilica was defended by Archbishop Guibert while Georges Clemenceau argued that it sought to stigmatise the Revolution.

The law was rescinded, but the Basilica was saved by a technicality and the bill was not reintroduced in the next session. A further attempt to halt the construction was defeated in 1897, by which time the interior was substantially complete and had been open for services for six years. Abadie died in 1884; five other architects continued with the work. The Basilica was not completed until 1914, when war intervened; the basilica was formally dedicated in 1919, after World War I, when its national symbolism had shifted.

The basilica was quite beautiful outside, and I should probably have gone inside to see the interior. At least it would have been warmer. But I am more of an "expansive panorama" tourist, and prefer more to do things and go places.

On the plaza at the top there were people selling seed to feed the pigeons. I bought a small amount and shared it with another visitor, and had her take a picture of me as some of the birds landed on my arm to eat the seeds. |

Here is the lady who took my picture. She and the little boy are obviously enjoying having all the birds crowd around to get fed. Holy Tippi Hedren, Batman! |

Up at the top of the stairs, there are good views of much of Paris. Although my sweater was adequate early in the morning when I started out, the day was growing progressively cooler.

|

The apartments and stores are built on levels, and the nearest you can get by car is the parking area that you can see at the bottom of the hill. So I left the Cathedral grounds at the top of the hill, and went back down the hill on this walkway. A very nice, and very typical view, of Paris. I bet this area is beautiful in the Summer.

Those type of buildings are very typical of what you find throughout Paris. Not too many buildings are very tall, and unlike the downtown areas of most US cities, the buildings are not antiseptic office structures, since people live, work and shop all in the same area. You are likely to pass a business, then some apartments, then some apartments over a store, then offices over a store, and so on.

Paris is very oriented to individual neighborhoods ("arrondisements"), so that you find the same kind of stores every few blocks or so. I never got any impression that thousands of Parisians would all travel a long distance to shop at some superstore, whether it be a K-Mart, a department store, or a supermarket. The city and the neighborhoods seem to be oriented on a much smaller scale. The largest store I was in seemed to be about the size of a medium-size drugstore, but it might sell meat, or bread, or bakery goods, or vegetables, or furniture, or anything. Looking at this particular picture made me wonder what the city looks like when it snows.

Presently, I descended the stairs you saw above, and continued my walk through Paris. It was getting quite cold this afternoon, so I started making my way back to the hotel (stopping in at one point in a little cafe for some coffee). I was continually impressed by the average age of the buildings. Only in our oldest cities does one find buildings from the 1800s or even earlier. But you have to remember that Paris, as a city, dates back to 500AD. But it is also a difference in attitude. In America, we seem to have to work hard to preserve the things that are old and interesting. Europeans wouldn't think of simply tearing them down and building something new. Perhaps that ties in with our fascination with what is modern, or "in." Europeans are more comfortable with tradition than we are, I think.

|

I asked someone about this, and I learned that most Europeans don't have a freezer as a matter of course in their homes, and this pretty much forces them to shop frequently. I wondered how they kept ice cream, and actually asked about that too; the answer I got was that there is almost always a store just a short distance from your door where you can get some. It also turns out that small (by our standards) refrigerators are about as common as they are here, and that most of the newer ones will have one of those small freezer compartments as part of them. But even so, because of tradition they have not come to use it very frequently, but still shop daily for what they need.

So I guess they could keep ice cream around if they wanted to. I learned when I was in London that only in North America do people use a lot of ice as a matter of course (although having been only to Northern Europe so far, where it is usually not very hot in the summer); in Europe, if you go into McDonalds and get a soft drink, you have to ask them to put ice in it, and, even when they do, it is just a very small amount. They are not trying to save money, or anything, since the franchise has the standard ice-making machine, but they are just not used to scooping up a lot of ice in a cup and then filling it with a drink.

A Walk along the Left Bank

|

I am going to walk to the Eiffel Tower and to a few other locales today, taking advantage of the good weather. From the Hotel Vendome, I headed south, crossed the Rue de Rivoli and cut through the Tuileries and the Place de la Concorde. I crossed the Seine to the south on the bridge at the Place de la Concorde, and then west along the Quay d'Orsay.

This picture was taken as I crossed the Tuileries heading towards the Place de la Concorde. |

I am on the Place de la Concorde bridge, crossing the Seine to the south, and this view looks southeast up the river. The Louvre complex is on the left bank, and the Orsay Museum is on the right bank. |

This entire area of Paris is amazingly scenic; we are right in the middle of the area where almost all tourists that come to Paris spend the lion's share of their time. I continued to be appreciative that Steve found this centrally-located hotel for me. The walk west along the Quay d'Orsay took me by the French Foreign Ministry and to the Pont Invalides- the bridge that crosses the Seine at the Grand Palace.

|

|

The Pont Alexandre III is the deck arch bridge that spans the Seine, connecting the Champs-Élysées quarter with those of the Invalides and Eiffel Tower. The bridge is widely regarded as the most ornate, extravagant bridge in the city, and is classified as a French Historic Monument. At the four corners of the bridge are ornate statuary like the one at right, that sits on the southeast corner of the bridge.

The Beaux-Arts style Pont Alexandre III, with its exuberant Art Nouveau lamps, cherubs, nymphs and winged horses at either end, was built between 1896 and 1900. It is named after Tsar Alexander III, who had concluded the Franco-Russian Alliance in 1892. His son Nicholas II laid the foundation stone in October 1896. The style of the bridge reflects that of the Grand Palais, to which it leads on the right bank.

|

The street along which I am walking is known locally and internationally by its official name- the Quai d’Orsay. The Quai becomes the Quai Anatole-France (fr) east of the Palais Bourbon, and the Quai Branly west of the Pont de l'Alma. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs is located on the Quai d'Orsay, and thus the ministry is often called the Quai d'Orsay as well.

The Quai (rue du Bac) has historically played an important role in French art as a location to which many artists came to paint along the banks of the river Seine. The building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was developed between 1844 and 1855 by Jacques Lacornée. The statues of the facade were created by the sculptor Henri de Triqueti.

|

The American Church in Paris is the first American church established outside the United States. It traces its roots back to 1814, and the present church building- located at 65 Quai d'Orsay here in the 7th arrondissement- dates to 1931.

In 1814, American Protestants started worshiping together in homes around Paris and at the Oratoire du Louvre temple. The first American sanctuary was built in 1857, on rue de Berri. The American Church in Paris was then, as now, an interdenominational fellowship, for all those adhering to the historic Christian tradition as expressed in the Apostles' Creed. It served both the expatriate American community, and a wide variety of other English-speaking people from different countries and denominational backgrounds.

Today, the American Church continues to minister to many Anglophone Protestants in Paris, with multicultural programming, and a congregation coming from some 40 nations and 35 Christian denominations.

Along the Seine itself, at least in this governmental area, a strip of park land has been reserved, so that Parisians will always have access to this beautiful feature of the city. It makes for a lovely view. I think it must be even more beautiful in the Spring and Summer than it is now in November. I continued walking along the river and around a curve to the southwest, where the Quai d'Orsay became Quai Bramly, and soon I found myself at another major bridge across the Seine.

|

Napoleon I ordered the construction of this bridge in 1807; it was to be named after his victory over the Prussians in 1806 at the Battle of Jena. Fortunes changed, and in 1814 Prussian General Blücher wanted to destroy the bridge before the Battle of Paris, as he had been present at the humiliating defeat of the Prussians at Jena. The Allied forces persuaded him to leave the bridge intact.

The structure was designed with five, 90-foot arches, and four intermediate piers. The initial construction, the cost of which was enormous at the time, was fully financed by the State and spanned six years from 1808 to 1814. The tympana along the sides of the bridge had been originally decorated with imperial eagles; these were replaced with the royal letter "L" soon after the fall of the First Empire in 1815 but in 1852, when Napoléon III ascended the throne of the Second Empire, new imperial eagles replaced them in turn.

Put in place in 1853, on the two ends of the bridge, are four sculptures sitting on top of four corresponding pylons; on the far end are a Gallic warrior and a Roman warrior, and on the Left Bank, where I am standing, are Arab and Greek warriors. Towards the second half of the 19th century, the inadequacy of the bridge's carrying capacity started to become a pronounced problem, and there were many calls to widen the 40-foot bridge.

It was not until 1937, with the prospect of the upcoming World's Fair, that the French government decided not only widen the structure but to repair the signs of deterioration. The bridge was widened to 110 feet, and two additional concrete elements were placed at either end, joined to the existing bridge with metal girders. Stone facings were used to protect the concrete tympana, the imperial eagles were put back in place and the four statues repositioned accordingly.

I walked to the other side of the bridge for a moment to see the Trocadéro Gardens and the Palais de Chaillot; both are situated on a hill, site of the former village of Chaillot. The hill was named for the Battle of Trocadero, in which the French captured the island of Trocadero from Spanish rebels in 1823; France had intervened on behalf of King Ferdinand VII of Spain, whose rule was contested by a liberal rebellion.

|

The building you see in my photo was built in 1937 to replace the old palace; it is the Palais de Chaillot. Designed in the "moderne" style, it still features two wings (actually separate buildings) shaped to form a wide arc. A wide esplanade leaves an open view from the Palais to the Eiffel Tower and beyond.

The buildings are decorated with quotations by Paul Valéry, and sculptural groups (like the one in my picture) throughout the grounds. The Palais de Chaillot actually houses a number of museums; the Musée national de la Marine (naval museum) and the Musée de l'Homme (ethnology) are in one wing, and the Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine, including the Musée national des Monuments Français, are in the other. There is still a theatre between them. It was on the front terrace of the palace that Adolf Hitler was pictured during his short tour of the city in 1940, with the Eiffel Tower in the background. It was here that the 1948 UN human rights declaration was adopted, and the building was also the first headquarters for NATO.

The Eiffel Tower

|

|

When you compare the aerial view to my photo, one interesting thing pops out. The aerial view is current, of course, taken somewhere in the mid-2010s, I presume. My picture is from 1980, and while I expect changes in most things that I photograph, an icon such as the Eiffel Tower should be timeless. Not so the Trocadero Gardens; what was a reflecting pool when I was here is, as you can see, now a garden. I descended the steps of the Palais and walked back towards Pont d'Iéna and the tower, going only as close as I could take another photo and get the entire tower into the frame. That turned out to be just midway down the side of the reflecting pool.

|

The statistics are amazing; it is 1,063 ft tall, about the same height as an 81-storey building, and the tallest structure in Paris. Its base is square, measuring 410 ft on each side. During its construction, the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monument to become the tallest man-made structure in the world, a title it held for 41 years until the Chrysler Building in New York City was finished in 1930. The tower has three levels for visitors, with restaurants on the first and second levels. The top level's upper platform is 906 ft above the ground – the highest observation deck accessible to the public in Europe (depending on just how you define "Europe", I understand).

But what about the "controversy"? Eiffel's firm proposed the design for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. Eiffel himself showed little enthusiasm, but he did approve further study. An idea for "a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top" took shape. Eiffel got on board with the idea, presenting it to the Civil Engineering Society in 1885, describing it as a symbol of modern engineering and the modern age.

In 1886, a budget for the exposition was passed and, a competition for desiging a centerpiece for the exhibition was announced. The requirements (entries had to include a study for a 1000-foot, four-sided metal tower) made the selection of Eiffel's design a foregone conclusion (somebody was thought to have been paid off). A contract was signed on 8 January 1887; the government gave Eiffel a quarter of the estimated 6.5-million-franc cost, but granted him all income from the commercial exploitation of the tower for a period of 20 years.

Almost immediately, opposition developed, most of it due to an arcane debate in France about the relationship between architecture and engineering. A number of artists joined together in the "Committee of Three Hundred" and a petition against construction was sent to the Minister of Works. It was not subtle:

| "We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years … we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal." |

Eiffel responded to the criticisms by comparing his tower to the Egyptian pyramids, and the exposition officials responded with support as well. These responses swayed many, but in any event, most concluded that the protest was irrelevant since the project had been decided upon months before, and construction on the tower was already under way.

Some of the protesters changed their minds when the tower was built; others remained unconvinced. Guy de Maupassant supposedly ate lunch in the tower's restaurant every day because it "...is the one place in Paris where the tower is not visible". By the turn of the century it was a national and Parisian symbol, and today it is widely considered to be a remarkable piece of structural art, and is often featured in films and literature.

The morning I was here, the queue was not very long for the elevator up to the first and second levels, but I decided to take the stairs. 600 steps later, I reached the second level. I discovered that while there are stairs to the top, they were closed to general tourists, and so the last two-thirds of my ascent was in a 20-passenger elevator. At the top and one the way up, I took a number of pictures, and I think that the best way for you to look at them is in a slideshow. That show is below. To get from one picture to the next, just use the "backward" and "forward" arrows in the lower corners of each slide; you can see where you are in the show using the index numbers in the upper left. I have put the descriptions for each picture (written in 1981) on the slide as well. Enjoy!

Notre-Dame de Paris

|

I did not record my exact route in my slide narratives back then, nor could I possibly reconstruct it now. But I can point to one stop I made- at Les Invalides- since I have a picture taken there, and I can approximate the location of another, fortuitous stop on the way, since I have a picture there, too.

|

My walk took me along Avenue de Tourville, which forms the southern boundary of the complex. That turned out to be right in front of a building in the complex called the Dôme des Invalides, a large former church in the center of the Les Invalides complex (but not in the center of the area of Paris called Les Invalides, since this includes the extensive park to the north of the complex that runs all the way to the Seine.

The dôme was designated to become Napoleon's funeral place in a law dated 10 June 1840. The excavation and erection of the crypt, that heavily modified the interior of the domed church, took twenty years to complete and was finished in 1861. Inspired by St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the original for all baroque domes, the Dôme des Invalides is one of the triumphs of French Baroque architecture. Jules Mansart, the architect and builder, raised its drum with an attic storey over its main cornice, and employed the paired columns motif. The general appearance is sculptural but tightly integrated, rich but balanced, consistently carried through, capping its vertical thrust firmly with a ribbed and hemispherical dome. The domed chapel is centrally placed to dominate the court of honor.

The interior of the dome is 350 feet high, and was painted by Charles de La Fosse with a Baroque illusion of space seen from below. The painting was completed in 1705. Marshal Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander in World War I, and Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, the author of France's national anthem, La Marseillaise, are both entombed here, but the most notable tomb at Les Invalides is that of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). Napoleon was initially interred on Saint Helena, but King Louis Philippe arranged for his remains to be brought to France in 1840, an event known as le retour des cendres. Napoléon's remains were first buried in the Chapelle Saint-Jérôme in the Invalides until his final resting place, a tomb made of red quartzite and resting on a green granite base, was finished in 1861.

|

I continued heading east through the 6th arrondissement towards Notre Dame. There is a lot to see in this area of the city, but I was intent on my destination. There were many small shops and boutiques, each very small by our standards and each tending to specialize in a single kind of item. Then I ran across a Baskin Robbins store- entirely by accident.

When I first got to Paris, I looked in the phone book to see if there were any stores here- figuring I might work in a few of them in my walks. I didn't find any stores listed, although, oddly, there was a listing for the company itself. I thought that was odd, but was anxious to get out and see things. But now, on my walk to Notre Dame, I happened on this one. Why wasn't it in the phone book, I wondered.

I went in and got my requisite scoop of ice cream and asked the young man behind the counter in my broken French why he wasn't in the phone book. His answer, in better English than my French (although I think he appreciated my effort) was that the store didn't have a telephone. He explained that most small stores don't have phones; they serve just their neighborhoods, and so folks know where they are; these small stores don't need to attract people from a distance away. (He also told me that even some stores with phones aren't listed, since listing in the phone book isn't free!).

Now that I knew the situation, I wondered how I could find out where the stores were. I called the Baskin-Robbins number the next day, but couldn't get them to read me a list of all the addresses. Anyway, how was I to get to all of them without knowing the city or having a car? I resolved that, if I ran across one, good, but that it would be impractical (and a poor use of my time in Paris) to go hunting for them. Maybe I will be here again with more time on my hands. I continued walking eastward, eventually crossing onto the Île de la Cité and over to Notre Dame.

|

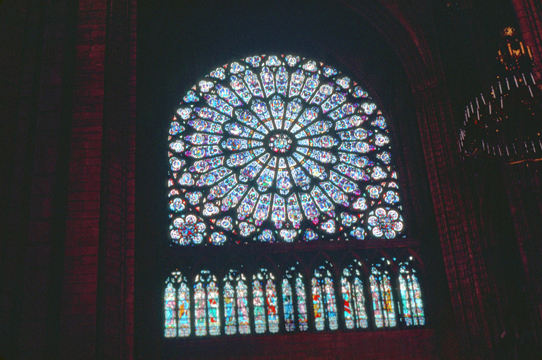

Notre-Dame de Paris ("Our Lady of Paris"), known simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral here on the Île de la Cité; the cathedral is widely considered to be one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture, and it is among the largest and most well-known church buildings in the world. The naturalism of its sculptures and stained glass are in contrast with earlier Romanesque architecture.

As the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the Archbishop of Paris, and the cathedral treasury contains a reliquary, which houses some of Catholicism's most important relics, including the purported Crown of Thorns, a fragment of the True Cross, and one of the Holy Nails. In the 1790s, Notre-Dame suffered desecration in the radical phase of the French Revolution when much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. An extensive restoration began in 1845, and since then the cathedral has remained perhaps Paris' second-most-famous landmark, after the Eiffel Tower. One thing that I find remarkable about traveling is that I get to see places and things that I have only seen pictures of before. I can't count the number of times I have encountered pictures or stories of Notre Dame in my school career and elsewhere, but nothing quite prepares you for seeing the thing up close and for real.

|

|

Notre-Dame de Paris was among the first buildings in the world to use the flying buttress. The building was not originally designed to include the flying buttresses around the choir and nave but after the construction began, the thinner walls grew ever higher and stress fractures began to occur as the walls pushed outward. In response, the cathedral's architects built supports around the outside walls, and later additions continued the pattern.

This was one building that I simply had to go inside; my visit inside Notre Dame would eventually turn out to be only the very first of more than 100 beautiful church buildings that I have gone into in the years since; it is continually amazing to me how much absolutely beautiful architecture, and how much stunning decoration, have been created in the name of religion. Certainly, we are all familiar with the huge amount of beautiful artwork that has a religious theme, but relatively few people have been inside many large churches (most of them Catholic, it seems) other than their own, and so they have little appreciation for the vast legacy of impressive buildings that the religious tradition has left us (impoverishing though it may have been to commoners, influenced to contribute much of their meagre wealth to Church coffers). I was particularly impressed with the stained glass windows:

|

|

In 1160, Bishop Maurice de Sully had the existing cathedral, founded in the 4th century, demolished; according to legend, Sully had a vision of a glorious new cathedral for Paris, and sketched it on the ground outside the original church. The bishop had several houses demolished and had a new road built to transport materials for the rest of the cathedral. Construction began in 1163 during the reign of Louis VII; Bishop de Sully went on to devote most of his life and wealth to the cathedral's construction. Construction of the choir took from 1163 until around 1177 and the new High Altar was consecrated in 1182. His successor oversaw the completion of the transepts and pressed ahead with the nave; the western facade had also been laid out, though it was not completed until around the mid-1240s.

Numerous architects worked on the site over the period of construction, which is evident from the differing styles at different heights of the west front and towers. Between 1210 and 1220, the fourth architect oversaw the construction of the level with the rose window and the great halls beneath the towers. The last significant design change occurred around 1258; since then, the appearance of the cathedral has remained almost exactly the same.

|

(Picture at left) I took this shot on the outside of the church to give you an idea of the amount of intricate carving that there is. Cathdrals and churches were intended to be as impressive as possible (influencing common folk to think that a religion with such beautiful structures must be powerful indeed). Other than churches, most public buildings were financed by the monarch, and he/she wanted them to be as impressive as possible (impressive buildings = powerful monarch). Religion has long been a potent force in Europe, so we find that many of the most intricate and exquisite structures are religious in nature.

(Picture at right)

|

|

I thought that Notre Dame was as impressive as I had always learned, and after visiting it I was looking forward even more to my side trip to Rheims and another major cathedral. It was getting past midafternoon, so I thought I should head on to see what else I could work in today.

|

Then, with the Place de la Bastille my next destination, I walked east until I came to that famous square, where I spent some time looking around. Then, with my light fading, I headed back west, passing the Louvre again and this time having a look at the Arc de Triomphe du Carousel.

One of the impressive things about Paris is that it seems to be the ultimate "walking city", and enjoyed every minute that I spent walking around town. I am pretty sure that if I lived in Paris, I would not have a car, as I never saw many places where more than a few of them could be parked. I have enough trouble finding a parking place in Chicago.

|

|

I crossed to the Right Bank and then headed east towards Place de la Bastille. The first part of my walk was right along the Seine; the city has kept most of the riverfront from being blocked by buildings; there is green space almost all the way along. Eventually, I had to diagonal up to the northeast to get to Place de la Bastille. The Place de la Bastille is the square where the Bastille prison stood until the "Storming of the Bastille" and its subsequent physical destruction between 14 July 1789 and 14 July 1790 during the French Revolution. No vestige of the prison remains. The square straddles 3 arrondissements- the 4th, 11th and 12th. The square and its surrounding areas are normally called simply "Bastille".

|

|

The column is composed of twenty-one cast bronze drums; it is 154 ft. high, containing an interior spiral staircase, and rests on a base of white marble ornamented with bronze bas-reliefs. The column is engraved in gold with the names of those who died during the July 1830 revolution. Over the Corinthian capital is a gallery 16 ft. wide, surmounted with a gilded globe, on which stands a colossal gilded figure, Auguste Dumont's "Génie de la Liberté" ("Spirit of Freedom"). The figure is perched on one foot in the manner of Giambologna's Mercury, the star-crowned nude brandishes the torch of civilisation and the remains of his broken chains. It was certainly impressive, although I wish that it had been earlier in the day.

|

|

The monument is 63 feet, 75 feet wide, and 24 feet thick. The 21 foot-high central arch is flanked by two smaller ones, and around its exterior are eight Corinthian columns of marble, topped by eight soldiers of the Empire. Napoleon's diplomatic and military victories are commemorated by bas-reliefs executed in rose marble. They depict the Peace of Pressburg, Napoleon entering Munich, Napoleon entering Vienna, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Tilsit Conference, and the surrender of Ulm. The quadriga atop the entablement is a copy of the so-called Horses of Saint Mark that adorn the top of the main door of the St Mark's Basilica in Venice.

That's the end of the pictures I took while walking around Paris on all the days I was here. But as I said earlier, I took two side trips outside Central Paris- one to Versailles and one to Rheims- but put each of those trips on its own page. So to continue with the trip to Versailles, use the first link below. But if you are finished with my trip to France, then use the second link; it will return you to the top of this page from which you can continue on through the photo album.

|

My Side Trip to Versailles |

|

Return to the Top of This Page |