|

January 21, 1971: A Circumnavigation of Central Tokyo |

|

January 17-19, 1971: Getting from Howze to Japan |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |

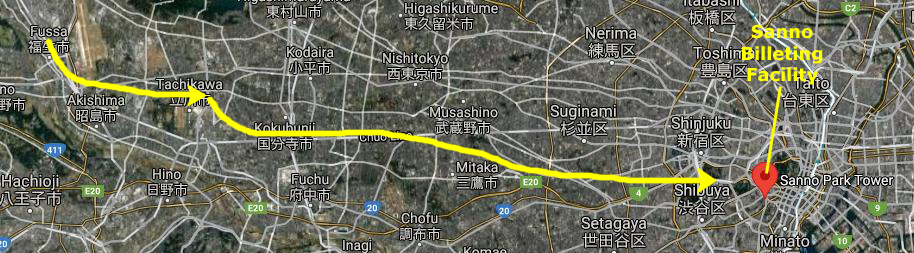

We landed at Yokota Air Base in the city of Fussa early in the morning of the Tuesday, January 19th. Fussa is a suburb of Tokyo, which is a good distance away. The Yokota Airbase is fairly large- both in number of personnel and in area. It also has one of the longest military runways in the Tokyo area. It is also a busy air transport hub and HQ for United States Forces Japan. Before we get started on the day's activities, let's orient you to where we are relative to downtown Tokyo.

|

The base is basically the same size today as it was in 1971, but there were fewer US personnel there in 2021 (about 14,000) than there are right now (about 20,000). In the years since my visit, of course, the restrictions on the Japanese military- already having been loosened from what they were at the end of World War II- would be pretty much removed. The Japanese have already been allowed a small air force for defense of the homeland while the United States uses Yokota as its main headquarters for any operations it conducts in the Far East.

The Vietnam War has resulted in an increased combat and airlift aircraft presence here. It is not only used for ferrying B-52 Stratofortresses to Southeast Asia but is also a base for the 65th Military Airlift Support Group- a headquarters organization for MAC airlift support squadrons in the Pacific and Far East. Fighter squadrons are deployed frequently from here to USAF-operated bases in Thailand to fly combat missions over North and South Vietnam, and to South Korea for alert missions. We are here at the tail end of all this activity, as we have found that there are already plans to relocate these squadron functions to Kunsan Air Base back in South Korea later this year. Yokota is slated to become a "non-flying station", and it may be that the exchange here may be downsized when all this happens.

|

Shopping in Yokota and Tachikawa

|

Even though it was late in the day, about 1500, we walked out the gate and headed through the town of Fussa to the Fussa train station. On the way we stopped in some of the many stereo and camera shops. In these shops, items are sold for the same price as in the exchange, so anytime the BX is out of a particular item, it can always be bought from these stores. The only reason we didn't immediately start buying everything in those stores was because we thought there might be problems with service (if needed) or exchange (if desired), but later we found that these are not really problems.

While this sort of scene may look like Korea, there is almost no resemblance. The shops are as small, but they are neater, cleaner, and more modern. Even the smallest shops have such conveniences as electric lighting and cash registers. I don't know why they bother with the registers, as most Japanese still double-check the totals on their abacus. Japanese are remarkably fast with it.

Dan and I felt that we should purchase the items other people had given us money for in the Exchange, but we ended up getting our own stuff at one of the large stores near the Yokota main gate. We found that a further discount is given if the customer pays in Yen rather than dollars or traveler's checks, so we made most of our purchases the very next day after having exchanged our MPC for Yen in the Finance Office on Yokota Base. This is opposite to Korea, where the storekeepers would be only too happy to get a harder currency than the Won, so it seemed to indicate here that the Japanese felt their own currency more stable than the dollar.

|

The signs around the station referred to another town up the train line called Ome. As I said, I don't have any experience at all hardly with riding trains or subways. In fact, this would be only my third train ride in my life. First, I came back from my summer in Montreat to Charlotte on a train in 1964. And my second ride was a short one when I went to Front Royal to visit Carter Fussell a few years ago. But you can't really even count those, as the United States, outside major cities, has relatively little train service- certainly no the kinds of trains people ride every day.

What I have learned in years since is that stations like this one always have signage naming the next stop down the line and the next stop up the line- one on either side of the platform. That's how you know which side of the platform to be on to get where you are going. I had looked at a map before we set out, and I have a good sense of direction, so I knew we would want to take a train going southeast from Fussa, and since I knew that when we were walking to the station we were walking west, we would need to go to whichever side of the platform had trains going to our left. It was easy to find the right platform when we got to the station. We would get a lot of experience in the coming days both on the aboveground rail system and also the Tokyo subway, but both worked the same way. And the signage was pretty good, especially in areas (like central Tokyo) where English-speakers would reasonably be expected to congregate.

|

|

Tachikawa was a bigger town than Fussa, home to the Tachikawa Air Base (more about that tomorrow when we come back to the Exchange), and we enjoyed walking around. In this picture taken right in the middle of the city near the train station shows the Isetan Department Store. The store is actually based in Shinjuku, part of central Tokyo, and there are a number of branches in Japan and a few outside Japan in the Far East.

|

When one accumulates enough of the little metal balls, they can be used to purchase items from the back of the game hall- cigarettes, chocolate, food and notions. I don't imagine you can make a killing at it, but an awful lot of people were trying. The parlors are all over Japan, grossing 700 billion Yen ($2 billion) annually. Trying my luck, I got 16 balls for 50 Yen (13 cents), parlayed that into 25 and bought a chocolate almond bar.

NOTE:

I would return to Japan once more, a stopover on my way back to the United States when my Korean tour ended. On that visit, I found a used Pachinko machine at a small store in Tokyo. The cost was reasonable, so I purchased it and had it shipped back to Fort Harrison. I have had it ever since, and even had it refurbished once I returned. It is in a closet, now, but it still works.

We ate dinner in a typical Japanese restaurant. Outside the restaurant is a showcase and one picks the food he wants from among the plastic replicas of the dishes served (there will be some pictures of these displays a bit later in our trip), and pays before he eats. We shared a meat and vegetable soup dish, with noodles, and a chicken and veal dish, with rice. We returned to the Officer's billet in Yokota to spent the night.

|

The Fussa station on the Ome Line is located in the western part of town, and it is built on a model that seems to be fairly common. The station is in the middle of the two tracks, and there is a "flyover" from both sides of the line to get to that middle station without necessitating your actually having to cross the tracks. (Sometimes, we would find, there is a tunnel instead of a flyover.)

Anyway, I stopped to take a picture looking "up the line" from the Fussa station towards the end of the line at Ome.

Once on the train, I took a couple of trackside photos that will give you an idea of what this suburban area looks like:

|

|

I think one of the striking differences between Korea and Japan is that while the people in Japan do live better, Japan would not appear that much different if all the houses were crammed together like they are in Korea. You can see here that even down "by the tracks" there are trees and room to live, unlike Korea.

|

Inside, Japanese commuter cars are clean and neat. They are crowded, but the people are polite about it. They are a pleasure to ride in, and it is relatively easy for a foreigner to find his way about the city and country by train even if he does not speak a word of Japanese. Maps of the train system are posted in every station and every car, and on each station platform is a sign that not only tells the name of that station, but names of the next stations up and down the line.

I took this picture just to show a typical car interior, but also because of the young woman who seemed lost in thought as she looked out the window of the moving train. One might also have thought that we would attract more attention than we did, being the only Westerners in this particular car. But then if I were riding a bus in Charlotte and happened to see a couple of Japanese, I would probably not think anything of it. Then, too, there are these two military installations nearby- Yokota and Tachikawa- and Americans are probably a very common sight.

For the rest of the day, we did a lot of shopping at the Tachikawa base, mailing a goodly bit of stuff back to guys in Korea.

|

|

Completing our shopping and walking around Tachikawa took us most of the day, and we did not get back to Yokota until late. We decided to eat out at a real Japanese restaurant, so we tried the Sugetsu, at the South end of the base. It was very Japanese, and the proprietor and waitresses did not speak much English. fortunately, the menu had sort of English subtitles, which, while they did not describe the dish completely, did at least tell what kind of meat it contained. We had sukiyaki, which I am sure you know about, tempura, which is deep-fried prawns, and a chicken and rice dish whose Japanese name escapes me. It was all really good, and not very expensive, about $1.50 each, I guess.

Then it was back to the billet to pick up our stuff (which we had left at the Officer Billeting Facility at Yokota) for our trip into Tokyo.

Our Transfer to the Sanno Hotel

|

We got our suitcases and went down to the Fussa station, armed only with the address of the hotel, our Tokyo map, and a map of the train and subway system. We rode down to Tachikawa, changed trains, and rode into Shinjuku. Once there, we stood around for a while, trying to find the signs for the subway, and then when we found those, we had to find the one train going to Yotsuya, which we thought was the closest station to the Sanno.

|

|

The original Sanno Hotel opened in 1932 on the southern side of Hie Shrine in Akasaka, near the Imperial Palace and National Diet Building. The privately owned hotel, with a Western design, was considered one of the top three accommodations in Tokyo, and was frequented by government and military officials.

The hotel was gutted by Allied bombing during World War II. The American occupation forces took over the facility in 1946 and rebuilt it for use first as American family apartments and later as VIP and senior officers’ billeting. From 1959 until the present, it has been used as field officer lodging (although company-grade officers, such as Dan and myself, can make reservations when the hotel is not full. We understand that the owners of the property (oddly enough, an automaker) want the building back (the US has been leasing it from the Japanese Government who, in turn, have been leasing it from its owners).

NOTE:

The Sanno Hotel will actually close in 1983, under an agreement by which the Japanese Government provided another location elsewhere in Tokyo for a newer, more modern facility- The New Sanno Hotel- which is still in use as of this writing in 2021. The building we are in will be demolished at that time, and a new, 44-story office tower (The Sanno Park Tower) will be constructed on the site in 2000. Since the original building is no longer here, my one picture of it at left will have to suffice.

|

One of the first little shops we ran across, just around the corner from the hotel, was a bakery, and the goodies were simply too enticing to pass up. I love cream-filled things, and it seems that the Japanese are even better at them than the French or the Germans. There is no silly picture of me enjoying my own pastry, because it never occurred to me to ask Dan for copies of his pictures from this trip. The only ones I have with me in them were the few that Dan took with my camera.

NOTE:

I should also say again, as I have said before in this album, that it's a shame that digital photography hadn't been invented when we took this Japan trip. We would have taken lots more, and lots better pictures, and it would have been a simple matter for us to give each other our own pictures. But we are still using film, and due to the cost of the film and of developing and printing, just clicking away at everything in sight would be a very expensive proposition. That is one reason why I have included in the album from this period just about every picture I took- leaving out only those that were truly spoiled in some way. For example, here is

a street scene in Akasaka

that I didn't focus correctly, but had no way of knowing until my slides came back to me weeks later.

This evening, we are wandering through Akasaka, a residential and commercial district of Minato, Tokyo, Japan, located west of the government center in Nagatachō and north of the Roppongi district. Akasaka (including the neighboring area of Aoyama) was a ward of Tokyo City from 1878 to 1947, and maintains a branch office of the Minato City government.

|

On the top row, left to right, meatballs, sweet and sour pork, meatballs, and beef stroganoff a la Japan. The second row is most fish and different kinds of vegetables. Down at the bottom are the meat and vegetable soups, and 4th row down, extreme right, is an omelet of noodles.

This is not the first time I've seen one of these displays, and so I already knew what I was looking at. At first, and even on close inspection, these look like actual dishes of real food, but then if you think about it, if the dishes were real, they would have to be replaced each day or so, and that would be a horrible waste of food. No, these dishes are actually plastic replicas of the actual dish that would be served to you. There is an entire industry in Japan composed of artisans who work in molded plastic and other materials to make an exact copy of an an actual dish, those copies to be placed in showcases like this one.

These artisans take great pains to make their plastic dishes exact replicas of the dish they are given to model; they look so real that unless you touch them or can smell them, a neophyte would never know that the replica wasn't real. If the artisan is given a bowl of the restaurant's pork soup, for example, and it happens to have two slices of pork floating on the surface, then there will be two plastic replica slices. Every tiny detail is duplicated with amazing accuracy.

Later in our trip, I discovered that the process works in reverse, as well. If a new restaurant opens, or if an existing one changes chefs, sometimes the plastic replicas become the model, and the chef takes great pains to make the dish that comes out of his kitchen look exactly like the plastic replica he is shown. I can't think of a better example of "life imitating art" than this!

It's a great system, though. You never have to wonder what your dish is going to look like- how much you will get, what all is in it, and so on. Because trust me- it is going to look precisely like the dish in the window. This is even better than putting pictures of the dishes on a menu!

I think I gained a little weight on our Japan trip, and restaurants like this were the main reason (not to mention the bakeries). All the food was excellent and, as you can see, incredibly cheap. The most expensive dishes were around 500 Yen, and with us getting near 360 Yen for each US dollar, that less than $1.50 for a huge dinner.

We continued wandering around until it was quite late- but not so late that Akasaka was slowing down much. There were a couple more interesting sights from this evening's walk.

A Gaming Parlor |

(Picture at left) I mentioned Pachinko before; this is another popular game. The object is to use the pinball machine to get four balls in a row or diagonal, and thus win more balls to play with. If you do well enough, the girl attendant will turn over one of the counters on the front of each table. When you finish, you can redeem the counters and extra balls for merchandise, like in Pachinko.

(Picture at right)

|

A Geisha House |

Geisha are trained in traditional Japanese performing arts styles, such as dance, music and singing, as well as being proficient conversationalists and hosts. Their distinct appearance is characterized by long, trailing kimono, traditional hairstyles and make-up. Geisha entertain at private parties, often for the entertainment of wealthy clientele. But they also are employed at establishments like the Mikado.

Modern geisha are not sex workers, though most Westerners (and not a few Japanese) don't know enough about this very honorable profession to make the distinction. I did not know it at the time, but historically most geisha were male, only later becoming a profession mainly characterized by female workers. A number of geisha have been classified as "living national treasures" by the Government of Japan, the highest artistic award attainable in the country.

At an establishment like the Mikado, customers pay for the attentions of a geisha, and the point is to perhaps share a meal, be entertained, and enjoy good conversation. Going further than that is frowned upon, and not just a little bit insulting. There are a number of these cabarets in the city, but we were told the Mikado is the best of them. Here, when you add the cover charge of 3000 Yen, a charge of 2500 Yen/hour/hostess, a service charge of 2-3000 Yen, then drinks (600-1000 Yen) and meals (3000 Yen and up), an evening's entertainment and conversation can easily run to thirty or forty thousand Yen- maybe $125. (Since my base salary is about $500/month, this ain't exactly cheap.)

Needless (or maybe not needless) to say, we did not go in to look around; that would have been tacky. Later in our trip, we did spend some time in a much smaller establishment; these make their money by hooking customers in and then hitting them with a lot of hidden charges. You can tell when a club is on the up and up when you see the charges all posted on the outside of the club, or when you are handed a charge sheet immediately upon entering.

As a matter of fact, at the end of our walk, we just returned to the Sanno for a good night's sleep- ahead of our first real sightseeing day in Tokyo.

|

January 21, 1971: A Circumnavigation of Central Tokyo |

|

January 17-19, 1971: Getting from Howze to Japan |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |