|

June 15, 1971: Osaka, Japan |

|

June 11-12, 1971: Getting to Japan; A Day in Tokyo |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |

As I indicated before, my intention on this trip to Japan was to get out of Tokyo and see as much of the country as I could in the limited time I had. In planning my itinerary (which would eventually include three major cities), I was definitely influenced by what my guidebook (Japan on $10 a Day) had to say. It had been so helpful last January that I had again brought it with me. I planned first to go to Kyoto, as the guidebook said it was not to be missed:

| "The most visited city in Japan, after Tokyo of course, is Kyoto, 330 miles to the west. From the 8th century until late in the last centry, it was Japan's capital, and it is still regarded (by all except Tokyo-ites) as the center of the nation's cultural, artistic, and creative activity. With its 2000 shrines and numerous historical landmarks, it should not be missed. The trip by express train from Tokyo takes only four hours." |

Getting to Kyoto

|

|

I followed the guidebook's other suggestion as to food for lunch. While the trains all have either dining cars or snack bars where you can get all manner of snacks to full meals (a full meal topping out at about $3), I stopped in a little store right in the station to buy a lunchbox to take on the train. It was all I needed for lunch, and was only $1.

Of course I took pictures from the train windows, but these were sometimes hit-or-miss, particularly because the train was going so fast. I had to use a fast speed, but this had the effect of reducing the light, and so some of the pictures came out darker than the scenery actually appeared.

|

|

Here is more of the scenery west of Tokyo and on the way to Nagoya:

|

|

In case you are interested, here is the route that our fast train took to get from Tokyo to Kyoto:

|

|

|

A little under three hours into our trip, we slowed as we came into the city of Nagoya, where we would make our only stop on the way to Kyoto. I know the pictures are kind of dull, but the weather was very cloudy- even overcast at times.

|

In 1610, the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu, a retainer of Oda Nobunaga, moved the capital of Owari Province from Kiyosu to Nagoya. This period saw the renovation of Nagoya Castle. The arrival of the 20th century brought a convergence of economic factors that fueled rapid growth in Nagoya, during the Meiji Restoration, and became a major industrial hub for Japan. The traditional manufactures of timepieces, bicycles, and sewing machines were followed by the production of special steels, ceramic, chemicals, oil, and petrochemicals, as the area's automobile, aviation, and shipbuilding industries flourished. Nagoya was impacted by bombing from US air raids during World War II. In the mid-20th century, Nagoya's economy diversified.

Nagoya is an industrial and transport center of Japan, home to the Nagoya Stock Exchange as well as the headquarters of Brother Industries And Toyota, among others. Nagoya is home of educational institutes such as Nagoya University, the Nagoya Institute of Technology, and Nagoya City University. Famous landmarks in the city include Atsuta Shrine, Higashiyama Zoo and Botanical Gardens, Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium, Nagoya Castle, and Hisaya Ōdori Park. The Nagoya TV Tower, quite close to Nagoya Central Station, is one of the oldest TV towers in Japan.

The picture above is the best one I have of Nagoya, but I did take a couple of other photos as the train moved through the south part of the city:

|

|

We stopped in Nagoya for just ten minutes, and less than an hour after we got started again we were pulling into the Kyoto Central Station, also in the southern part of the center of town.

My Lodgings In Kyoto/Kyoto City

|

Staying at a ryokan is a little different from staying in a hotel, my guidebook pointed out. First, you remove your shoes in the lobby (usually where you step up from ground level into the lobby area). Next, you are shown to your room, where a cup of tea and a traditional sweet or cracker will be waiting. If it’s already evening, you will change into the yukata (light robe) that the ryokan provides. Depending on where you stay, you'll either be served dinner in your room or you will dine in a common room with other guests. After dinner, you will have a chance to schedule your bath, and while you are doing that, someone will go into your room and lay out your futon.

Ryokan, the guidebook said, come in all sizes and in all gradations of western-influenced style. I had thought while on the train that my preference would be for the smaller inns as those most likely to afford a glimpse of true Japanese living. So when I got to Kyoto, I followed the suggestion in the guidebook and stopped in to the JTB (Japan Travel Bureau) to arrange my stay.

The guidebook (you can tell that I relied on the book quite a bit while in Japan) suggested that I might be able to find an English-speaking clerk to help me, and while I did not find someone with whom I could easily have a long discussion of current events, say, I did find a very nice young girl (early twenties, perhaps) who understood what I wanted.

|

The first thing I did was to take a picture, and that is it at right (the wooden structure with the bamboo mat hanging down the front). The street was comprised of many small, moderately old structures which appeared well kept-up. There were a couple of little restaurants, my ryokan, and also what appeared to be private homes. There was a good deal of signage, but of course I did not know Japanese. The only clue that the building in front of which I was standing was a hotel was a little circular sticker "JTB" on the glass door.

The taxi was more modern than those in Korea, with the little meter that tells you just what the fare is. I think it was only about 150Y to get from the station to the ryokan. (NOTE from 2022: At the time I was in Japan this time, the exchange rate was right around 300Y to the dollar, so you can see how relatively cheap things seem to be. But keep in mind that this is all relative; my base salary is about $500 a month, so while an $8 hotel room seems cheap, it was about 1-2% of my monthly salary. So if you were making $100K a year in 2022, it would be as if you were staying in a hotel room costing $160 a night- not really what we would think of as "cheap".)

|

(I do apologize for the quality of that picture. I have had trouble with my flash attachment; even though it appeared to be functioning, it turned out to be out of sync with the camera, and I didn't correct the problem until somewhat later.) The only other furnishing was a small chest. No bed was in evidence, but the guidebook said not to worry. The entire hotel was constructed of wood, about three stories tall, so very unlike any American hotel that it is difficult to describe. Think more along the lines of a private home. I was very impressed by the quiet beauty of the ryokan and its setting. The building rambled up and down narrow stairs, and it seemed as if each room looked out on the beautiful garden the trees of which you can see. Everything was incredibly neat and clean.

(Note from 2022: I have tried to find out whether the ryokan is still there- as I have tried to find out about many of the places and people that have appeared in these pictures so far. I didn't think to keep a diary when I left for Korea, although the narratives I wrote for my pictures would seem to constitute one. Sadly, though, I did not record the kind of details that would allow me to zero in on where some of my pictures were taken, and this will continue to be true heading into the future. Landmarks and major structures are one thing, but in the half-century since I was in Korea, much has undoubtedly changed. Who knows? Maybe a Kyoto expressway has come right through this neighborhood. But still, I wish that I'd recorded the name of the Ryokan, or kept the directions, or noted the street name. But who could have known that a quarter century on I would have the ability I have now, to put all these pictures into an online diary, and relate them to maps and aerial views? Hindsight is 20-20, as they say, but even so, I which I'd been more meticulous in recording things.)

My First Outing In Kyoto

|

I do know two things. First, even though I cannot locate the exact street or address, I am sure my ryokan is in the area around the yellow star at the right side of the aerial view at left. I remember that it was fairly close to the main station, and that it was near some green hills. Second, my walked ended at an area of old Japanese structures, and I was able to compare these to online views of the Higashi Honganji Temple- marked with the other yellow star on the aerial view.

Other than that, all I know is that I did cross the Kamo River, which flows north-south through the city. So I won't be able to identify particular streets or intersections- not 50 years later when all but the most substantial structures have probably been altered or replaced.

Kyoto is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan, and the cultural anchor of a substantially larger metropolitan region which, at the time of my visit, had between a quarter million and half million residents. Kyoto is one of the oldest municipalities in Japan, having been chosen in 794 as the new seat of Japan's imperial court by Emperor Kanmu.

|

The first identifiable landmark from my pictures was, of course, the Kamo (Duck) River. The riverbanks are popular walking spots for residents and tourists. In summer, restaurants open balconies looking out to the river. There are pathways running alongside the river on which one can walk, and some stepping stones that cross the river. The water level of the river is usually relatively low; less than three feet in most places. During the rainy season, however, the pathways sometimes flood in their lower stretches.

Kyoto is considered the cultural capital of Japan and a major tourist destination. It is home to numerous Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, palaces and gardens. Prominent landmarks include the Kyoto Imperial Palace, Kiyomizu-dera, Kinkaku-ji, Ginkaku-ji, the Higashi Honganji Temple, and the Katsura Imperial Villa. Kyoto is also a center of higher learning, with Kyoto University being an institution of international renown.

Kyoto was considered as a possible target for an atomic bomb at the end of World War II because it had a population large enough to possibly persuade the emperor to surrender. In the end, at the insistence of Secretary of War Stimson, the city was removed from the list of targets and replaced by Nagasaki. Since the city was largely spared from conventional bombing as well, Kyoto is one of the few Japanese cities that still have an abundance of prewar buildings, such as the traditional townhouses known as machiya- one of which is my ryokan.

|

Note from 2022:

I actually sent this picture and the two others of the downtown area below to a couple of historical societies in Kyoto to see if anyone could identify the streets for me, but I have not gotten any responses as yet. If I do, I will return to this page and add that information. But for now, all I have are a few random street scenes taken during my afternoon walk.

Getting around in Kyoto calls for trolley transportation. The guidebook had a complete list of the trolley numbers and where the routes went, and how much rides cost (cheap) so that getting around was no problem.

I must say that the whole city is neat and clean, with wide avenues every so often. Kyoto still shows the influence of its heyday as the Imperial Summer city. Here are two more pictures that I took downtown as I turned north from the area around the train station:

|

|

The Higashi Honganji Temple

|

Before we get to the temple, however, I do have an interesting connection that I can draw from my walk in 1971 and the pictures I took then with the information that is available to me today. In 1971, I actually visited the temple first and then saw in my guidebook that there was a department store just south of the temple grounds that offered good views of the temple complex from its rooftop restaurant/amusement area.

So, on my way back to the ryokan, I stopped into the store, made my way up to the rooftop, and went out to see what I could see.

If you will look at the inside of the yellow square, you will note that there is a white building just south of the temple complex, and then another building south of that. This last building is the one that is only partially inside the yellow square and is/was, I think, the department store. I have no ide if it still is, or if the building I visited has been torn down and something else built in its place.

But now comes the interesting thing. First, let me show you the two pictures that I took from the top of that structure. Both these images look north, with the left-hand image below looking directly north at the Higashi Temple grounds, and the right-hand image looking more northeast across Kyoto:

|

|

I want you to look closely at the bottom area of the left-hand image. You will note that there seems to be another building, lower than the one I am standing on, between me and the temple grounds.

|

You can probably see the building I am referring to- north of me and not as high. Look at the architecture of the northwest corner of the building, and then compare it to the building at the bottom of the left-hand picture above. You will see that the building has the same protruding section as the building I saw in 1971. I know that the picture and the aerial view were not taken from the same place, so that the perspective is off. But I think it is obvious that the building appearing in my 1971 picture still exists today.

This is unusual; other than historical buildings, I think this is one of the first times in this photo album where I have been able to confirm the existence of a structure that appeared in one of my pictures. This is hardly unusual when the picture is a recent one, but these two pictures are over a half-century old, so I think the existence of a common, everyday commercial building fifty years later is unusual.

Anyway, I thought that it was interesting that even fifty years on I was able to relate one of my early photographs to something still in existence. But now we can take a look at the Higashi Honganji Temple itself.

Higashi Hongan-ji, or, ″the Eastern Monastery of the Original Vow″, is one of two dominant sub-sects of Shin Buddhism in Japan and abroad, the other being Nishi Honganji (or, 'The Western Temple of the Original Vow'). It is also the name of the head temple of the Ōtani-ha branch of Jōdo Shinshū in Kyoto, which was most recently constructed in 1895 after a fire burned down the previous temple. As with many sites in Kyoto, these two complexes have more casual names and are known affectionately in Kyoto as Honorable Mr. West and Honorable Mr. East. I visited the Eastern temple grounds.

|

Higashi Honganji was established in 1602 by the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu when he split the Shin sect in two (Nishi Honganji being the other) in order to diminish its power. The temple was first built in its present location in 1658.

The temple grounds feature a mausoleum containing the ashes of Shin Buddhism founder Shinran. The mausoleum was initially constructed in 1272 and moved several times before being constructed in its current location in 1670.

At the center of the temple area is the Founder's Hall, where an image of the temple's founder, Shinran, is enshrined. The hall is one of the largest wooden structures in the world at 250 ft. long, 190 ft. wide, and 125 ft. high. The structure you see in my picture at left was constructed in 1895.

The Amida Hall to the left of the Founder's Hall contains an image of Amida Buddha along with an image of Prince Shōtoku, who introduced Buddhism to Japan. The hall is ornately decorated with gold leaf and art from the Japanese Meiji Period. The current hall was constructed in 1895.

|

Various parts of Higashi Honganji, including the Founder's Hall and Amida Hall, burned down 4 times during the Japanese Edo Period. Monetary assistance was often given to Higashi Honganji by the Tokugawa Shogunate in order to rebuild. The Great Tenmei Fire in Kyoto caused many temple buildings to burn down in 1788, and the temple was rebuilt in 1797. An accidental fire destroyed many of the temple buildings in 1823 and these were rebuilt in 1835.

After burning down once again in 1858, the destroyed halls were quickly and temporarily reconstructed for Shinran's 600th Memorial Service in 1861. However, these temporary halls burned down in a city-wide fire caused by the Kinmon incident on July 19, 1864. The temple finally started to rebuild in 1879 after the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and once conflict caused by the Meiji Restoration of 1868 had settled down. The Founder's Hall and Amida Hall were completed in 1895, with other buildings being restored by 1911. These buildings comprise the current temple as I photographed it today.

Wandering around the temple complex was immensely interesting. The buildings were quite large and made exclusively of wood- painted and gilded. The courtyard itself was grassy areas transected by wide walkways. The walkways and the broad aprons were composed of fine white pebbles.

|

During the twentieth century, Higashi Honganji was troubled by political disagreements, financial scandals and family disputes, and has subsequently fractured into a number of further sub-divisions. The largest Higashi Honganji grouping, the Shinshu Otaniha has approximately 5.5 million members, according to statistics.

However within this climate of instability the Higashi Honganji also produced a significant number of extremely influential thinkers, such as Soga Ryojin, Kiyozawa Manshi, Kaneko Daiei and Haya Akegarasu amongst others.

After my long train trip, getting to and checking into my ryokan, and the afternoon walk, I thought I would return to the ryokan to relax and enjoy the evening. I was served a wonderful meal right in my room, and along about 8 o'clock, a middle-aged woman came to my room to tell me that it was my turn for a bath. The guidebook had been very informative about what to expect, so I wore my robe and only took it off when all the ricepaper doors had closed. I actually took my bath outside the large tiled pool, using one of the little stools and the handheld shower. Then, I stepped into the moderately hot pool to luxuriate for the remainder of my time in the bath.

When my time was almost up I committed my only faux pas by reaching down to the bottom of the pool to unstop the drain and let the water out. It had not drained for more than thirty seconds or so before one of the ricepaper panels just by me slid open and another woman asked me in broken English to replace the stopper- which I did quickly. As soon as I'd done so, the panel slid closed again, and no mention was ever made of the incident by any of the staff. But I tell the story as an example of how different cultures treat the same functions- like bathing, in this case.

A Chance Encounter

|

Following the directions in the guidebook, I walked towards the main train station to find the appropriate streetcar to take north to the Palace grounds. I found the correctly-numbered car, paid my fare, hopped on and sat down.

That when one of the most interesting occurrences of all my time in Japan (and, really, Korea too, for that matter) happened.

In the middle of downtown, near the train station, I got on a trolley going to another of the stops the guidebook admonished me not to miss- the former Imperial Palace, used until the royal household and the seat of government moved to Tokyo in 1869. Sitting across from me were a couple of young men carrying what appeared to be either briefcases or school bags. They were quite young- maybe high teens or low twenties; it is hard for me to judge just how old orientals are, since I have had so little experience. One of them struck up a conversation with me; he spoke remarkably good English.

|

Then one of the young men offered to guide me to the ones which were really important, but he went on to say that they were on the way to the university right now to attend a meeting of their English Club, but that after that they, and perhaps others, might want to accompany me to some of the interesting sites. (Think of your high school days; there were probably clubs for any languages taught at your school- like a French Club or Latin Club.) When I expressed interest and thanks for the offer, the young man suggested that I accompany them to the college and actually attend the club meeting. That would take about an hour, but afterwards he'd be free to spend the day guiding me around.

At first I was a little suspicious, as anyone in the States would be if they were accosted on a public bus to come with them somewhere. But in talking, they seemed sincere, and I figured that so long as it actually WAS a university, I shouldn't have any problem. I also got the impression that the young men's status would be enhanced if they showed up to the Club meeting with an actual English-speaker in tow. So I agreed.

The guys showed me on my tourist map where the college was, and pointed out a couple places I should see- including the Imperial Palace and also a traditional Zen garden (that only Japanese usually visited). I did not record the name of the University, but based on the current Kyoto map and the location of the Zen Garden we visited first, I think that the college we went to was Ritsumeikan University. The young man also prevailed on me to speak to the group, which I found flattering and interesting.

|

We got to the college and the classroom where the meeting was just beginning, and I just sat for a time watching and listening until the young man I'd met introduced me to the group and I came up to speak for a few minutes and then answer questions. I will say that I enjoyed that hour immensely. Everyone was listening avidly and at the end asked questions that were insightful. I enjoyed being "on stage" (and perhaps this feeling would have an impact on career decisions I would make a few years hence).

I don't have any pictures of the the group, although I wish I'd taken one or two. I was pleased to have been asked to talk, and I just made a few observations on the differences between the United States and Japan, and then answered some questions that the students had, supplementing my answers with drawings on a blackboard. Most of the questions were thoughtful, dealing with politics, ecology and student affairs. Other questions were more about everyday life in America. All of them were fun and interesting to answer. Everyone seemed genuinely interested, and I enjoyed myself.

When the meeting was over, two other guys joined our group, and you can see a picture of all four of them above, left. Then the young man who'd first spoken to me suggested that we have a quick refreshment at the school and then head off to Ryoan-ji, a nearby Zen Garden.

Ryoan-ji: A Classic Zen Garden

|

|

I think it is immensely interesting to compare my photograph, taken of course in 1971, with the aerial view, which, according to Google, was taken sometime during 2019-2020. The rock at the left side of my picture is the black dot beneath the red star in the aerial view. Knowing that, you can compare my picture the aerial view and you will see that there are five rock "islands" in the field of carefully-raked pebbles, and that those "islands" are in exactly the same positions today that they were in 1971. I don't know about you, but I think that is pretty amazing.

|

The garden is meant to be viewed from a seated position on the veranda of the hōjō, the residence of the abbot of the monastery. The stones are placed so that the entire composition cannot be seen at once from the veranda; no matter where you sit, you can never see all fifteen stones. The maximum is 14- one shy of the entire composition. It is said that this is to impress upon the viewer that unless one attains true enlightenment, some part of the natural world will always remain hidden.

In my photo at left, two of my student guides are in the nearground, but more interesting is the unknown woman looking directly at the camera with a knowing expression.

The wall behind the garden is an important element of it. It is made of clay, which has been stained by age with subtle brown and orange tones. When the garden was rebuilt in 1799, the height of the wall was decreased, and a view over the wall to the mountain scenery behind came about. At present this view is blocked by trees.

|

The site of the temple of Ryoan-Ji was an estate of the Fujiwara clan in the 11th century. The first temple and the still existing large pond were built in that century by Fujiwara Saneyoshi. In 1450, Hosokawa Katsumoto, another powerful warlord, acquired the land where the temple stood. He built his residence there, and founded a Zen temple, Ryōan-ji. During the Ōnin War between the clans, the temple was destroyed. Katsumoto died in 1473, and in 1488 his son, Hosokawa Masamoto, rebuilt the temple.

The temple served as a mausoleum for several emperors. Their tombs are grouped together in what are today known as the "Seven Imperial Tombs" at Ryōan-ji. The burial places of these emperors would have been comparatively humble in the period after their deaths. These tombs reached their present state as a result of the 19th century restoration of imperial sepulchers which were ordered by Emperor Meiji.

There is controversy over who built the garden and when. Most sources date it to the second half of the 15th century. According to some sources, it was built by Hosokawa Katsumoto, the creator of the first temple of Ryōan-ji, but others think it was built by his son. A small group of scholars say that the garden was built by the famous landscape painter and monk, Sōami (died 1525). The date of construction isn't agreed on either. Some sources say the garden was built in the first half of the 16th century, while others reckon later, during the Edo period, between 1618 and 1680. There is also controversy over whether the garden was built by monks, or by professional gardeners, called "kawaramono", or a combination of the two. One stone in the garden has the name of two "kawaramono" carved into it.

In addition to the Zen stone garden, Ryoan-ji has other gardens and ponds on the grounds of the temple. Here are two pictures of the grounds around which we wandered:

|

|

Also on the grounds the guys led me to the Burmese Pagoda (Stupa), a memorial to Japanese soldiers killed in Burma. In looking at the Google aerial view, I at first thought the "Pagoda" and "Burmese Stupa" were two different things, but it turns out that they are same thing.

|

|

We spent a bit over an hour here at Ryoan-ji. I though the Zen Garden was immensely interesting, but there were other things to see as well.

|

I also want to say a word or two about the fountain adjacent to the Burmese Pagoda. It was not actually a water fountain in the traditional sense. It is a famous stone water basin, with continually-flowing water. People use one of the cups on long rods to dip into the water to drink, but the waer is actually provided for the purpose of ritual purification.

This is the Ryōan-ji tsukubai, which translates as "crouch"; because of the low height of the basin, the user must bend over to get the water, and this is a sign of reverence and humility. The students pointed out the inscription on circular face of the basin which translates literally to "I only sufficiency know" or more poetically "I know only satisfaction". Intended to reinforce Buddhist teachings regarding humility and the abundance within one's soul, the meaning is simple and clear: "one already has all one needs". Meanwhile, the positioning of the tsukubai, lower than the small platform on which one stands to drink from it, compels one to bow respectfully (while listening to the endless trickle of replenishing water from the bamboo pipe).

I thought Ryoan-ji was immensely interesting, and I was glad we had come here. The guidebook did mention Ryoan-ji and its Zen Garden, but it was kind of far down the list of places to go, so without the students I probably would have missed it.

Kinkaku-ji: The Golden Pavilion

The site of Kinkaku-ji was originally a villa belonging to a powerful statesman, and its history dates to 1397, when the villa was purchased by a shōgun and transformed into the Kinkaku-ji complex. When the shogun died the building was converted into a Zen temple by his son and according to his wishes. During the Ōnin war (1467–1477), all of the buildings in the complex aside from the pavilion were burned down. The pavilion stood for 400 years until it was burned down in 1950 by a novice monk, who then attempted suicide. He was convicted of the arson and died in 1956. The present pavilion structure dates from 1955, when it was rebuilt.

|

The pavilion houses relics of the Buddha, and was an important model for other temple buildings in Kyoto. The pavilion incorporates three distinct styles of architecture. The first floor (The Chamber of Dharma Waters) is in the "shinden" style, reminiscent of the residential style of the 11th century imperial aristocracy. It is an open space with adjacent verandas and uses natural, unpainted wood and white plaster. The second floor (The Tower of Sound Waves) is built in the style of warrior aristocrats, or buke-zukuri. The second floor contains a Buddha Hall and a shrine dedicated to the goddess of mercy, Kannon. The third floor (Cupola of the Ultimate) is built in traditional Chinese Zen style which depicts a more religious ambiance in the pavilion.

The roof is in a thatched pyramid with shingles, and the building is topped with a bronze phoenix ornament. The gold leaf covering the upper stories hints at what is housed inside: the shrines.

The Golden Pavilion is set in a Japanese strolling garden, and the pavilion itself extends over a pond that reflects the building. The pond contains 10 smaller islands. The zen typology is seen through the rock composition; the bridges and plants are arranged in a specific way to represent famous places in Chinese and Japanese literature.

|

|

Nijo Castle

|

As it turned out, they said, they were familiar with a trolley line that began just outside the Kinkaku gates and headed directly south towards the train station and which went right by the Nijo Castle. To go from here to the Imperial Palace, however, would require a more circuitous route on the trolley system, so we opted for the straight shot.

You can see on the map at left that Nijo Castle is just a short distance southwest of the Imperial Palace, so we planned to just walk the short distance to the Imperial Palace from Nijo.

Nijō Castle is a flatland castle that consists of two concentric rings of fortifications, the Ninomaru Palace, the ruins of the Honmaru Palace, various support buildings and several gardens. The surface area of the castle is 68 acres, of which about 90,000 sq ft is occupied by buildings.

In 1601, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, ordered all the feudal lords in western Japan to contribute to the construction of Nijō Castle, which was completed during the reign of Tokugawa Iemitsu in 1626. While the castle was being built, a portion of land from the partially abandoned Shinsenen Garden (originally part of the imperial palace) was absorbed, and its abundant water was used in the castle gardens and ponds. Parts of Fushimi Castle, such as the main tower and the karamon, were moved here in 1625–26. Nijo Castle was built as the Kyoto residence of the Tokugawa shōguns. The Tokugawa shogunate used Edo as the capital city, but Kyoto continued to be the home of the Imperial Court. Kyoto Imperial Palace is located north-east of Nijō Castle.

We were coming down towards town from north and a little west of Nijo Castle, so when we arrived we were on a major street just to the west of the complex.

|

I have put a current aerial view of the Nijo Castle complex at right so I can explain how we went through the complex. We entered the complex by crossing a bridge over a moat, and I have marked this as "Entry". We walked through what was once an outer area of the castle, came a bid south, and walked across another bridge over another moat into the castle complex proper. The students told me we could get to the top of one of the corner towers, so we came south along the moat, and went up some stairs to the top of the southwest rampart.

On the aerial view, I have put the legend "Photo" on top of that rampart because that was the viewpoint from which I took my first picture of the Nijo Castle.

|

In 1867, the Ninomaru Palace, in the Outer Ward, was the stage for the declaration by Tokugawa Yoshinobu, returning the authority to the Imperial Court. In 1868 the Imperial Cabinet was installed in the castle. The palace became imperial property and was declared a detached palace. During this time, the Tokugawa hollyhock crest was removed wherever possible and replaced with the imperial chrysanthemum.

In 1939, the palace was donated to the city of Kyoto and opened to the public the following year. Now it is one of the most visited sites anywhere in Kyoto. While its buildings are not so grand as at the Imperial Palace, people come to see the European-style moat-and-wall system that was fairly common in Europe at the time.

We walked eastward through the inner ward, and crossed the bridge marked "Exit/Entry" into the outer ward where most of the buildings in the complex are located. This outer ward is not protected by moats and bridges; this is where the buildings used for ceremonial and administrative purposes are located. We stopped at two of the major buildings here in the outer ward- Ninomaru Palace and Honmaru Palace.

|

The castle is an excellent example of social control manifested in architectural space. Low-ranking visitors were received in the outer regions of the Ninomaru, whereas high-ranking visitors were shown the more subtle inner chambers. Rather than attempt to conceal the entrances to the rooms for bodyguards (as was done in many castles), the Tokugawas chose to display them prominently. Thus, the construction lent itself to expressing intimidation and power to Edo-period visitors.

The building houses several different reception chambers, offices and the living quarters of the shōgun, where only female attendants were allowed. One of the most striking features of the Ninomaru Palace are the "nightingale floors" (uguisubari) in the corridors that make a chirping sound when walked upon. Some of the rooms in the castle also contained special doors where the shogun's bodyguard could sneak out to protect him.

|

A word about these "nightingale floors":

Nightingale floors are floors that make a chirping sound when walked upon. These floors were used in the hallways of some temples and palaces, the most famous example being here at Nijō Castle. Dry boards naturally creak under pressure, but these floors were built in a way that the flooring nails rub against a jacket or clamp, causing chirping noises. It is unclear if the design was intentional. It seems that, at least initially, the effect arose by chance. An information sign in Nijō castle states that "The singing sound is not actually intentional, stemming rather from the movement of nails against clumps in the floor caused by wear and tear over the years". Legend has it that the squeaking floors were used as a security device, assuring that none could sneak through the corridors undetected.

The English name "nightingale" refers to the Japanese bush warbler, or uguisu, which is a common songbird in Japan.

|

Honmaru Palace contains 17,000 square feet and the complex has four parts: living quarters, reception and entertainment rooms, entrance halls and kitchen area. The different areas are connected by corridors and courtyards. The architectural style is late Edo period. The palace displays paintings by several famous masters, such as Kanō Eigaku.

Honmaru Palace was originally similar to Ninomaru Palace. The original structures were replaced by the present structures between 1893 and 1894, by moving one part of the former Katsura Palace within the Kyoto Imperial Enclosure (Kyoto Gyoen, the enclosure surrounding the Kyoto Imperial Palace) to the inner ward of Nijō Castle, as part of the systematic clearing of the disused residences and palaces in the Imperial Enclosure after the Imperial Court moved to Tokyo in 1869. In its original location the palace had 55 buildings, but only a small part was relocated. In 1928 the enthronement banquet of Emperor Hirohito was held here.

It was getting late in the afternoon, so we decided to forego waiting for a tour of Honmaru Palace and instead walk from the Nijo complex a few blocks northeast to the Imperial Palac. On the way, we passed through the Nijo Gardens.

The castle area has several gardens and groves of cherry and Japanese plum trees. The Ninomaru garden was designed by the landscape architect and tea master Kobori Enshū. It is located between the two main rings of fortifications, next to the palace of the same name. The garden has a large pond with three islands and features numerous carefully placed stones and topiary pine trees.

|

|

The Seiryū-en garden is the most recent part of Nijō Castle. It was constructed in 1965 in the northern part of the complex, as a facility for the reception of official guests of Kyoto and as a venue for cultural events. Seiryū-en has two tea houses and more than 1,000 carefully arranged stones.

Passing through the gardens, we left the complex on the north side and headed northeast to the Imperial Palace.

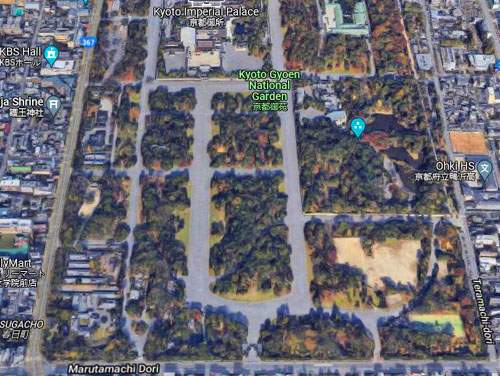

The Kyoto Imperial Palace

|

|

We intended so simply walk through the garden heading north to the actual Imperial Palace and its many important structures; when we did so, we used the main path on the west as it led directly north to the southern gate of the palace area. The garden is more of a park, with broad walkways as you can see in the two pictures below:

|

|

The Kyoto Imperial Palace is the former ruling palace of the Emperor of Japan. Since the Meiji Restoration in 1869, the Emperors have resided at the Tokyo Imperial Palace, while the preservation of the Kyoto Imperial Palace was ordered in 1877. Today, the grounds are open to the public, and the Imperial Household Agency hosts public tours of the buildings several times a day.

|

I did get a picture of the Kenreimon Gate, however. For state ceremonies, the dignitaries would enter through this gate, which has a cypress-wood roof, and is supported by four unpainted wooden pillars. This gate would have been used on the rare occasions of the Emperor welcoming a foreign diplomat or dignitary, as well as for many other important state ceremonies. The wall that you can see extending out from the gate in both directions runs completely around the complex, and there is a gate in each direction- all of them being different.

Passing through the Kenreimon, the inner gate Jomeimon would appear, which is painted in vermilion and roofed in tile. This leads to the Shishin-den, which is the Hall for State Ceremonies. I did learn later that even had the Palace been open today, that one needs to arrange for, or at least sign up for, tours of the various structures- although if the Palace is open at all, you can go into the main courtyard and just look around, but you can't wander unaccompanied all throughout the complex. Had I known about this (the guidebook said you could arrange to join a tour, but I didn't recall it saying you had to) I would definitely have done so when I first arrived.

My Students and I Part Ways

|

Now I had to make my own way back to my ryokan. I had my guidebook with me, and the little Kyoto map showed the the Kamo River was just a ways east of me, so I thought I leave the palace grounds at the north and then walk east along the main street over to it and then follow it south back to the ryokan.

If you will look at the aerial view of the palace grounds and park above, you will see than when I reached the river, I was just south of the point where it seems to split into two branches as it heads upstream. I thought that confluence interesting enough to take a picture looking north, and that is the picture you can see at left.

I made my way back to the ryokan, a trip that took me about an hour- mostly because I was just walking slowly to see what I could see. One of the things I saw was a bakery, and I stopped in for a cream-filled snack. I had dinner in a little Japanese restaurant just down the street from the ryokan. Then I returned to the inn, had my bath (not repeating my faux pas from the night before), and turned in.

Mount Hiei

|

Mount Hiei is a mountain to the northeast of Kyoto, lying on the border between the Kyoto and Shiga Prefectures. The main feature of the mountain is the temple of Enryaku-ji, the first outpost of the Japanese Tendai sect of Buddhism, was founded atop Mount Hiei by Saichō in 788 and rapidly grew into a sprawling complex of temples and buildings.

Due to its position north-east of the ancient capital of Kyoto, it was thought in ancient geomancy practices to be a protective bulwark against negative influences on the capital, which meant that the mountain and the temple complex were politically powerful and influential. The temple complex was razed by Oda Nobunaga in 1571 to quell the rising power of Tendai's warrior monks but it was rebuilt and remains the Tendai headquarters to this day.

I actually didn't know about much of this before I set out, and I found that I didn't have enough time to explore all the temple buildings, which were a ways from the ropeway station. So I had to content myself with experiencing the trip up and down and the views of Kyoto from the top.

The funicular to the top of Mt. Hiei was similar to the one I rode on earlier this year when Dan and I came to Japan and went on the Golden Course to Mt. Fuji, so I knew what to expect.

|

There is also a narrow road that comes up the eastern side of the mountain; the funicular came close to this road at a couple of spots. (NOTE from 2022: In the 1990s, this road was expanded and tolled, and now it is common for visitors to get to the top of the mountain by car. While the car trip is common, though, there is limited capacity for parking at the top, and this is probably why the road is a toll road- so that the number of cars can be controlled.

Also common on the roadway are small buses that run a few times a day from both Kyoto and the "Shiga" side of the mountain. The attractions on the mountain are quite spread out, so there are regular buses during the daytime connecting the attractions, and my guidebook detailed where and how to utilize these shuttles. I did not use them, as I barely had time to get to the top of the mountain, take some pictures, and return to Kyoto Station for my trip to Osaka.

In the picture above, you can deduce that this is one of the "two car" funiculars; as one car is ascending the other is descending, and they pass each other in the middle.Here are two more pictures that I took while on the funicular up to the top of Mt. Hiei:

|

|

The views from the top of the mountain were, as advertised, quite spectacular. Unfortunately, the top of the mountain was covered with clouds, and the city of Kyoto could not be seen. The view to the other side, however, was relatively clear. Here are three of the best views I was able to get:

|

|

|

After spending a half hour at the top of Mt. Hiei, I took the funicular back down and grabbed a taxi back to the ryokan. There, I collected my stuff, and left for the train station. I did not actually have to check out, as I had paid for the inn when I made the reservation two days ago on my arrival in Kyoto.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

June 15, 1971: Osaka, Japan |

|

June 11-12, 1971: Getting to Japan; A Day in Tokyo |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |