|

November 22, 1997: My 51st Birthday |

|

October 11-13, 1997: My Nephew Ted Visits Dallas |

|

Return to the Index for 1997 |

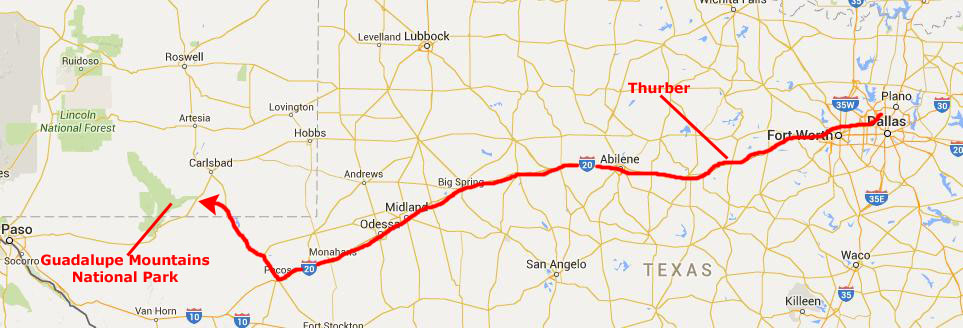

We didn’t have a great deal of vacation time this Fall to do an extensive camping trip, so we decided to do a four-day hiking trip to Eastern New Mexico. We left Dallas after Fred got off work an hour or so early, heading out to the Guadalupe Mountains. We planned to do some hiking there, visit the UFO Museum in Roswell, hike and possibly camp in the White Mountains north of Ruidoso, visit Dog Canyon near Alamogordo and also do some other hikes in the area.

Usually, on these multi-day trips, I have an index page and put each day of the trip on its own web page. On this short trip, though, we only took about 40-45 pictures, so I think we'll just put everything on this one page. If it takes a little longer to load, that's the reason.

Traveling to the Guadalupe Mountains

|

We left after work on Wednesday, had dinner in Thurber, and stopped in Abilene for the night. It is always a long drive out to New Mexico, but when you get as far west as you can on the first night, it's not so bad. Be nice if it were closer, or if we didn't have jobs, of course. On Thursday, we continued along I-20 to Pecos, where we are already south of New Mexico.

|

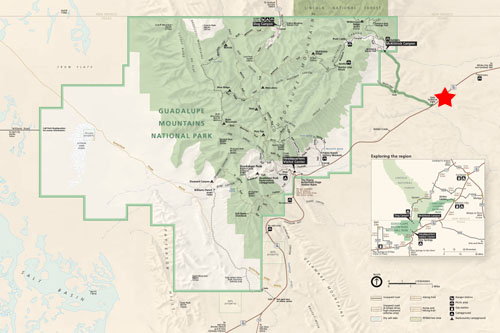

The county road doesn't go directly to the National Park; it actually end in US Highway 180/62 between the town of Carlsbad and the National Park, so we had to head southwest a few miles to get there.

The McKittrick Canyon Hike

|

Guadalupe Mountains National Park was created to set aside the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas for the enjoyment of everyone; this is the only really mountainous area of the state, although there are lower mountains at Big Bend. This park contains Guadalupe Peak, the highest point in Texas at 8,749 feet.

Located generally northeast of El Paso, the park also contains El Capitan, long used as a landmark by people traveling along the old route later followed by the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line. Visitors can see the ruins of an old stagecoach station near the Pine Springs Visitor Center. Although we didn't plan to do so this evening, camping is available at the Pine Springs Campground along the highway we are on and at Dog Canyon, where we have camped and hiked before.

Attractions include the restored Frijole Ranch House, which is now a small museum of local ranching history and is the trailhead for Smith Spring. The park covers 86,367 acres (134.95 sq mi) and is in the same mountain range as Carlsbad Caverns National Park which is located about 25 miles to the north in New Mexico.

Numerous well-established trails exist in the park for hiking; the most famous, if not the most traveled, is the Guadalupe Peak Trail offers perhaps the most outstanding views in the park. Climbing over 3,000 feet to the summit of Guadalupe Peak, the trail winds through pinyon pine and Douglas-fir forests and offers spectacular views of El Capitan and the vast Chihuahuan Desert. Fred took me on that trail five years ago- the year after we met.

|

|

McKittrick Canyon, one of the most popular destinations in the park, was the stop we wanted to make this afternoon. During the Fall, McKittrick Canyon comes alive with a blaze of color from the turning Bigtooth Maples, in stark contrast with the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert. A trail in the canyon leads to a stone cabin built in the early 1930s, formerly the vacation home of Wallace Pratt, a petroleum geologist who donated the land in order to establish the park.

|

Of course, we're not going to do that hike again; this afternoon, we'll hike the McKittrick Canyon Trail, a 6-mile round trip out and back. McKittrick Canyon is often named as the most beautiful spot in Texas; the steep towering walls of McKittrick Canyon protect a rich riparian oasis in the midst of the Chihuahuan Desert.

McKittrick Canyon is a bit separated from the main park area; it is managed as a "day-use only" area with limited visitation hours. Access to the canyon is via a 4.2-mile gated side road that leads to the mouth of McKittrick Canyon from U.S. Route 62/180. Here the National Park Service maintains a parking area, restroom facilities, and visitor center, which is staffed most of the year by volunteers.

We found ourselves pulling into the parking area just after noon. It was a beautiful day for a hike, and I for one was very much looking forward to it.

|

It isn't apparent from the trail map that we will be ascending over a thousand feet as we travel from the Visitor Center to the farthest point we will reach on the trail- an area called "The Notch". But I think the graphic gives you an excellent appreciation for the topography of the land we'll be traversing on the hike.

Although we took pictures out and back, I think the best way to show them to you is to put them generally in order from the Visitor Center to The Notch, regardless of whether we took them outbound or on the return.

We parked at the Visitor Center, got our stuff together, and then headed off up McKittrick Canyon. The Canyon is named for the two small creeks that flow through it and it has been described as “the most beautiful spot in Texas.”

|

| "While the towering walls of McKittrick Canyon protect the riches of diversity, its precious secrets are hidden in riparian oasis. It is no wonder that it has been described as the "most beautiful spot in Texas." But for all its magical power, that delights thousands of people each year, its fragility reminds us that our enjoyment cannot compromise its necessity for survival. It must survive - not for us, but for all that lives within." |

While no place in Texas can compete with the hardwood forests of New England for Fall color, McKittrick Canyon is one of the few places in Texas where such color can be found (given that the forested areas of East Texas are largely pine). And very soon after we began our hike, we began to encounter that color (see the picture at right). But this wasn't even the peak of it; that would not occur for another couple of weeks, since it had been, so far, a mild Fall.

Thousands of visitors each year come to Guadalupe Mountains National Park to visit McKittrick Canyon during the latter part of October or early November for this sensational display of fall colors. In this tiny part of west Texas, the foliage (brilliant reds, subtle yellows, and deep browns) contrasts dramatically with the flavors of the arid Chihuahuan desert that includes century plants, prickly pear cacti, blacktail rattlers, steep canyon walls and crystal clear blue skies.

|

But as we ascended into the relatively cool and more sheltered environment farther up the canyon, a flowing stream of clear water appeared and we encountered deciduous trees such as oak, ash, and Bigtooth Maple, and the bright Fall colors stood in stark contrast to the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert. Click on the thumbnail images below to see more of the Fall color here in McKittrick Canyon:

|

About 2.4 miles into the hike, we passed the Wallace Pratt Lodge that was built by Wallace Everette Pratt (1885-1981), a petroleum geologist who once owned most of McKittrick Canyon. In 1959, Pratt donated 4,988 acres of his ranch to the National Park Service and seven years later, on 15 October 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the act establishing Guadalupe Mountains National Park. It was not until 1972, however, that the park was dedicated and formally opened to the public.

|

After another mile, we came to a really unique geological feature- the Stairway at the Grotto. This amazing feature looks very much like the old ruin of an amphitheatre- just like the ones in Athens or Rome. It isn't, though; it's the result of water erosion acting on layers of limestone- layers you can easily see in the picture at right. In that picture, Fred is setting up his tripod so we could both go over and sit on the "stairs" to have our picture taken. You can see that picture here. Beyond the "Stairway" the hike to McKittrick Ridge continues up one of the steepest trails in the park, and we enjoyed that trail- it was a bit challenging and the views were spectacular. Towards the end of our hike (we would not go all the way to the top of McKittrick Ridge), we passed through " The Notch", which is actually a very, very narrow canyon. Because it is so narrow, and also angled, it is said that sunlight only reaches the floor of the notch for a few minutes and only on about half the days of the year.

We went through The Notch, and hiked just a bit further. We could see the peaks above us, and we could see that it would be quite a while before we got to the top of the ridge, so we turned and headed back down the trail.

According to archeological evidence unearthed in and near the canyon, the earliest inhabitants occupied the area over 12,000 years ago. Only stone-chipped tools, bone fragments and bits of charcoal remain to reconstruct the ways of their lives. More recent discoveries, such as mescal pits and pictographs, help weave a more complete story of prehistoric life in the Guadalupes. Because of these discoveries, certain areas of the canyon have been closed so that archaeologists can do thorough studies.

The weather was lowering a bit and clouding up when we reached the parking area. We had a snack at the car, and then headed off up US 180 towards Carlsbad. We’d already been to the Caverns, so we continued up through Carlsbad, then through Artesia and then up to Roswell. The scenery was great along the way, although by the time we reach Roswell it was dark. We got a room for the night and had a really good Mexican dinner at one of the local restaurants.

The UFO Museum in Roswell

Only if you've been living under a rock since the late 1940s would you wonder why there is a UFO museum in Roswell. But just in case, what's the deal? The one thing everyone agrees on is that in July 1947, something happened northwest of Roswell, New Mexico, during a severe thunderstorm. Did a flying saucer crash? Did a weather balloon come down? The incident remained a matter of local lore for quite some time.

In the early 1980s, leading UFO researcher Stanton Friedman came across the story and began the search for information and witnesses. That research brought him to Roswell looking for Lt. Walter Haut, the public information officer at Roswell Army Air Field in 1947. He was still living in Roswell and remembered the press release and the orders from his commanding officer.

Friedman’s investigation also led to many other individuals, military and civilian, who had information to add to the Roswell Incident story. Other researchers helped and what they uncovered was basically this:

| "The debris recovered at the site by rancher W. W. "Mack" Brazel was gathered up by the military from the Roswell Army Air Field under the direction of Major Jesse Marcel, the base intelligence officer. On July 8, 1947, public information officer Lt. Walter Haut issued a press release under orders from base commander Col. William Blanchard. The release said basically that the Army had, in its possession, a flying saucer. The next day another press release was issued, but this time from Gen. Roger Ramey, stating it was a weather balloon." |

|

In early 1990, the idea of a home for information about the Roswell Incident and other UFO phenomena was fostered by Lt. Haut. He got together with another Roswell participant, Glenn Dennis, and the two sought a home for the UFO Museum. It opened in that year but has changed venues a couple of times before landing at its current location.

(The Roswell UFO Museum is currently a 501c3 non-profit educational organization with the mission of educating the general public on all aspects of the UFO phenomena. The museum maintains its position as the "serious" side of the UFO phenomena.)

While I am skeptical that there is anything at all to all the "sightings" of UFOs that seem to have begun in 1947, I was looking forward to going in the museum to have a look around. This isn't the only "conspiracy theory" that I'm skeptical about. You can add the Kennedy Assassination, Marilyn Monroe's death and other events to the list. (I might point out, since I am actually writing this in 2015, that the granddaddy of them all is just a little under four years in the future from our visit to Roswell.)

|

The museum was quite a trip. The personnel were just a little bit “freaky,” but the exhibits were immensely interesting. The controversy over the incident began with Friedman's investigation, and in 1980 one of the first "Roswell" books was published. A more exhaustive reference book detailing Roswell witness accounts was published by Schmitt and Randle in 1991. The Roswell Incident was gaining international attention, and that led to the opening of the museum.

Many of the Roswell investigators assisted in the organization of the International UFO Museum & Research Center, which was incorporated on September 27, 1991. In December 1996, the Tourism Association of New Mexico awarded the International UFO Museum & Research Center its coveted "Top Tourist Destination of New Mexico" Award. As it turned out, the museum we visited today, its most recent location, opened on earlier this year.

The exhibits were mostly very interesting, but I think the staff were even more so. I don't recall any tinfoil hats, but I don't think that at least one woman staffer was far away from wearing one. (Whether the staff are doing a bit of tourist schtick or not I couldn't really be sure. But we did enjoy our visit!

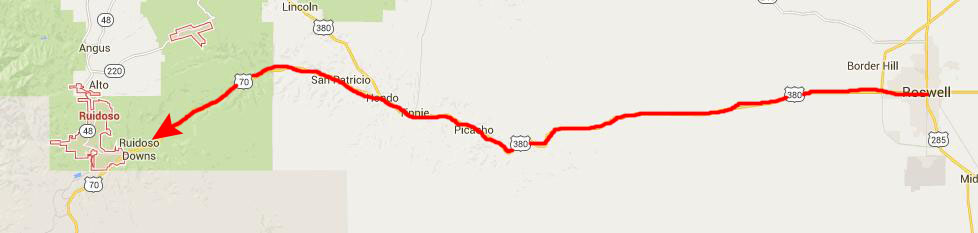

We headed west out of Roswell and on to Ruidoso. Just west of downtown, we passed an interesting house, although I am not sure why Fred decided to take a picture of it.

Hiking in the White Mountain Wilderness

|

The town of Ruidoso Downs (where most of the facilities for the Ruidoso ski areas are located) was a little over an hour from Roswell. As we drove through town, before angling up New Mexico 48 to the White Mountain Wilderness, we made note of the motels in town, so that if we decided not to try to camp we would know of some places to stay.

|

Incidentally, it was then that we discovered that camping was very, very limited nearby, and so we decided that when we were done hiking we would just go back and stay in one of the motels in Ruidoso Downs.

The White Mountain Wilderness is a protected wilderness area within the Lincoln National Forest, Smokey Bear Ranger District. The White Mountain Wilderness is located in the Sierra Blanca Mountains of south central New Mexico, approximately 25 miles northwest of the town of Ruidoso Downs.

The White Mountain Wilderness was established as a primitive area by the United States Congress in 1933 and was included in the National Wilderness Preservation System in 1964. This wilderness area contains approximately 49,000 acres of land in a rectangle approximately 12 miles on a side. It consists of mainly a long, northerly running ridge and its branches. The west side of this ridge is extremely steep and rugged, while the eastern side is more gentle with broader, forested canyons and some small streams.

The ski resort was deserted at this time of the year, as there had as yet been no snow (not nearly cold enough), and, apparently, the ski area does not make its own. A little later in our trip the weather did change dramatically, however, and it might be that the ski area opened not long after we were here hiking. We found the trailhead without too much problem and we headed off. The first part of the trail climbed through the forest up to the ridgeline.

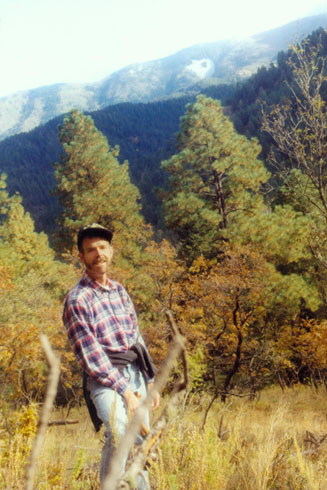

|

|

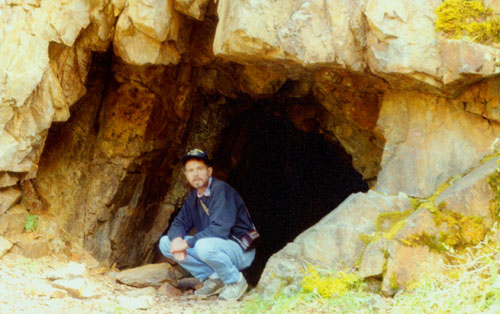

The trail continued upward at a steady pace. The going was not difficult, but we could certainly tell we were climbing. Elevations in this area range from 6,400 feet at Three Rivers Campground on the western side of the wilderness area to 11,580 feet near Lookout Mountain near Ski Apache. The summit of Sierra Blanca (White Mountain) is located on the Mescalero Indian Reservation and is reached by a trail from Lookout Mountain. At 11,973 feet, Sierra Blanca is the southernmost mountain in the continental United States to rise above timberline. Our trailhead was at about 7,500 feet, and our hike would take us up to just shy of 10,000 feet. This area, which bordered directly on the land belonging to the ski resort, had once been a center for various kinds of mining, although nothing on a really large scale. But there were remnants of the mining activity, at various spots along the trail. Fred took a second shot of me with some of the mining ruins, more to try out a filter effect than for any other reason, and it turned out rather well, I thought. You can have a look at it here.

Fred on the Crest Trail |

|

Top of the Crest Trail |

There are four different life zones within this wilderness area: pinyon-juniper, ponderosa pine, mixed conifer, and sub-alpine forest, plus alpine tundra found at the summit of Sierra Blanca just outside the wilderness boundary. Abrupt changes in elevation, escarpments, rock outcroppings, and avalanche chutes make for striking contrast and scenery.

|

The area is also interspersed with meadows and grass-oak savannahs, which are the result of forest fires. The weather is dry and windy in springtime, with temperatures ranging from 32° to 80°. July and August are the rainy months with frequent afternoon showers and high temperatures averaging 85°. Snows in winter do not typically begin until mid-November, and snowfall averages 6 feet or more (hence the reason for Ski Apache. Low temperatures during winter average around 22° but have reached as low as -15°.

Water sources are not abundant, but do exist in the form of small streams or springs scattered throughout the area- some of which we crossed. Although fishing is permitted within the wilderness area, few fish are found due to the small size of most streams. Although the streams run well most of the year, in times of severe drought, they may be non-existent.

|

One thing we didn't see was much wildlife, although it is indeed present here in the Wilderness. Animals that roam this area include mule deer, elk, black bear, turkey, porcupine, badger, bobcat, gray fox, coyote, skunk, spruce and rock squirrels, and numerous species of mice, moles, and birds. Feral hogs are also becoming abundant (and a bit of a problem) in this region.

After a few hours on our hike, we came to the furthest point we wanted to go to. We had come out into high alpine meadow, and the views were just tremendous in all directions. We could have gone further, but it was getting cloudy and a bit cooler. Here in the meadow, we took two more pictures I want to include here:

We are in the high meadow, at the end of the Crest Trail. With his trusty tripod, here is Fred as we look north and east along the crest of the mountains. Until we got to the top, we’d been hiking through cool, dark, moist forest, but up here the terrain gives way to grassland. I can only imagine that this spot would be pretty cold and desolate once the snows begin and all through the winter. |

We passed a number of these trail markers on the hike. This whole area is criss-crossed with trails, from here north through the Lincoln National Forest, east towards Ruidoso, and south through the Sacramento Mountains, past Cloudcroft and the other end of the Lincoln Forest, and to Three Rivers. Much of it is backpacking, although only a single overnight is required to get to Cloudcroft. |

Fred got out his panoramic camera, set up the tripod, and took a couple of good pictures. They are below:

|

|

But this was the end of the trail for us, so we retraced our steps to the ski area, and drove back into Ruidoso, where we got a room at a Days Inn Motel. We had another good Tex-Mex dinner at a little place called the Casa Blanca right in downtown Ruidoso and some ice cream at a local shop. Then we headed back to the motel and a good night’s sleep.

Hiking Through Dog Canyon Near Alamogordo

|

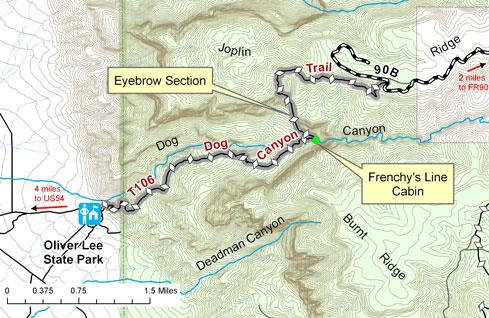

We drove leisurely down through Alamogordo and stopped and had some lunch, and then went a bit south of the city to the Oliver Lee Memorial State Park, which had a good campground. The park has two main tracts of land- one to preserve a canyon in the Sacramento Mountains (Dog Canyon) and the other to protect the 19th-century ranch house of early New Mexico settler Oliver Lee. The park is of median size for New Mexico, where the 30-odd state parks range in size from 24,000 acres to just 30; ranked by size, Oliver Lee Memorial is right in the middle.

The elevation of the park is about 4,400 feet, although that measurement is taken at the little visitor office near the park entrance. Most of the actual land area of the park is a good deal higher, with the far end of the Dog Canyon Trail reaching an elevation of 7,600 feet.

|

So we wouldn't have to do it in the dark (should our hike run long), we went ahead and paid our park fee to secure the campsite and we set up our tent. This didn't take all that long, for we are getting pretty routine about it.

We had investigated the hikes in New Mexico before we set out on the trip, and the Dog Canyon hike seemed to have a lot going for it. We enjoy hikes that have enough challenge to make it interesting, and we have a definite preference for hikes that end at or follow water features. This hike had both characteristics.

|

|

From the Interpretive Center, the Dog Canyon National Recreational Trail climbs to provide views of the Tularosa Basin and the Organ Mountains. Nearby are the community of Alamogordo and the White Sands National Monument. We should get views of all of these on our hike.

|

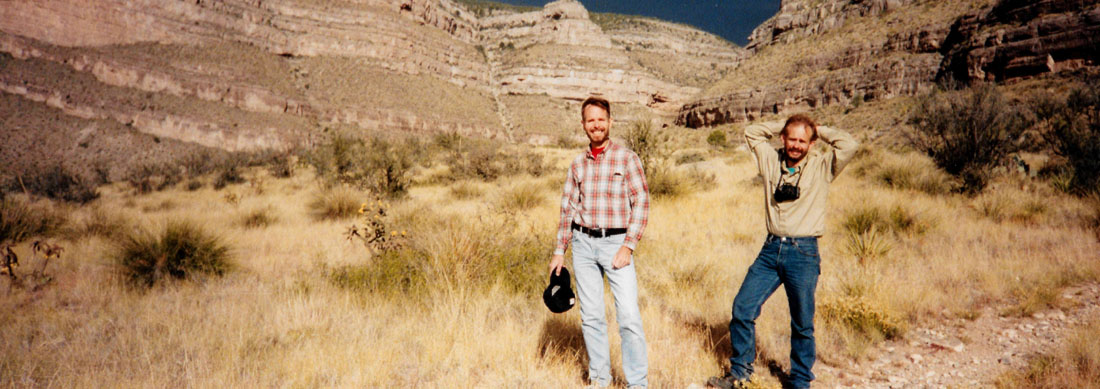

It began as a series of switchbacks taking you above the campground, and then headed off into the Sacramento Mountains. The view at left is looking south back towards the campground, which is out of sight around the ridge line behind me.

I should point out that although I had my camera with me, I discovered right after we started out that something was wrong with it; I think it was the reflex mirror that had come out of adjustment. Nothing happened when I pressed the shutter. So I just carried the camera along, but did not take a single picture on the hike. That's why all the pictures on this hike are of me (although I should have had the presence of mind to take pictures of Fred with his camera).

A short while after we started out, the trail crossed an open plain, and the mountains in the background were kind of neat. So Fred set up his tripod, and took a panoramic picture:

|

This trail is essentially the same one used for over 4000 years first by prehistoric people seeking a route into the mountains, later by Apaches, and then by historic ranchers. The trail climbed the canyon's south slope for the first 3 miles, gaining about 1,400 feet, before arriving at a grassy oasis of cottonwoods, willows and the stream.

|

We passed the remains of a small rock cabin built by ranchers in about 1930. As we hiked along and got higher, the views of the Tularosa Basin and the glistening white gypsum of White Sands National Monument get progressively better.

By the end of the second mile, we had climbed quite a ways up, and the vegetation began to change to greener low bushes. There were even some trees about, but it was mostly fairly dry grassland. At one point, we found a natural staircase leading the trail up onto the grassy plain.

After coming up onto the plain, the trail leveled out for quite a ways as we continued to walk back up into the canyon itself. Once in the canyon, we found a small spring-fed creek running through the area, and I sat down on the rocks beside it. The stream was so small that it didn't really show up in any of the pictures that Fred took this afternoon. In springtime, I imagine, there is a lot of snowmelt and then, I also presume, this valley is a good deal more scenic.

We passed through a steep, winding section of the trail called the Eyebrow, that was the scene of an 1878 skirmish between Apache and a U.S. Cavalry detachment. The soldiers had tracked an Apache raiding party to Dog Canyon, intending to capture them and send them back to the reservation. The Indians led the way up the trail, and when the soldiers were halfway up the steep slope the Apaches bombarded them with rocks, boulders, and gunfire from above, ending the chase.

At one point, Fred noticed an interesting rock formation. He didn't think it was just a layer of some kind of sedimentary rock, since the thin layer seemed to have a defined beginning and end, and he came to the conclusion that it was a fossil of some kind, perhaps a snake or worm of some kind. It would have been pretty large for a land worm, but perhaps there may have been a sea creature with that shape. Fred stuck his foot in the shot to give it perspective.

|

The water feature was almost dry, with just a few rivulets and small pools We suspected that there was water flow under the surface, as there were bigger pools back up towards the back of the canyon and the water had to go somewhere.

This time I noticed an interesting rock formation, and sat down on it to give Fred's picture some perspective. Fred wasn’t sure whether the depressions in the boulder I am sitting on were made by people or not. The depressions did look much like the same kind of pestle-like formations that we have seen elsewhere and which were thought to be man-made, so it is certainly possible.

Oliver Lee Memorial State Park is at the base of the western escarpment of the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico. It contains Dog Canyon and land to the north of the canyon. The canyon is bisected by a perennial stream, a rarity in the Chihuahuan Desert. Water is a vital resource here; the stream found in Dog Canyon has created a riparian environment in Oliver Lee Memorial State Park that is unique for the area. The stream is kept flowing by rain and snowmelt. The water seeps up from the ground in springs that naturally occur in the limestone formations of the park. The stream dries out just to the just of the park and the remaining water flows underground. It supports a small variety of insects and amphibians, but no fish.

We spent a good deal of time back here at the end of the trail, wandering around the cliffs and looking at the water seeps. Fred set up his tripod and took a couple of panoramic shots; this time, the panoramas were vertical. So for you to see them, I have had to put them in scrollable windows below:

The cliffs were pretty interesting, there was some fall color still left, and there was a bit of water to add interest, so the destination was a good choice. It was getting on towards late afternoon and getting noticeably colder. Perhaps the arrival of the much-heralded cold front.

|

Trails always look different going one way as opposed to the other, so while you might think that it would be boring covering the same ground over again, it really isn't- or almost never is. At another spot, we passed a small stand of yucca, and while I tested the sharpness of the needles, Fred snapped the picture at right.

We got back to the beginning of the switchback trail leading down into the campground, and it was getting late. Before we lost our light, Fred took two more pictures. One was taken from the top of the switchbacks and the other was taken from the bottom of them- when we were almost back to the campground. I thought we’d be able to see our campsite, but we couldn’t, as it was hidden by the promontory of the ridge.

Twenty minutes after that last picture was taken, we were back at our campsite. We relaxed for a while and then began the dinner routine. Fred has a cook set and a little butane burner, so we usually combine a few cans of something and have a stew of sorts for supper. It would be easier to do sandwiches, but on these hiking trips we usually do those for lunch. After dinner, we took all the utensils over to the washing station and cleaned them up and got everything put away.

Indeed, there was a large contingent of boy scouts, and they occupied campsites all around us. They were pretty noisy through dinner and after; we buttoned ourselves up in the tent about eleven, settling in to sleep as the scouts quieted down. We got about two hours of it- sleep, that is.

At first we thought that what awakened us was the boy scouts making more noise, and in a way, that was true. But the reason they were shouting was that when we awoke we were in the middle of the fiercest winds we’ve encountered in our camping thus far. The cold front had arrived with a vengeance. There was a bit of rain, but mostly just wind. It was playing havoc with the Scouts’ campsites and there was a lot of yelling and running about. We thought we were in a sheltered position but, as it turned out, the wind was so strong that it blew our tent completely down. We had little hope of setting it up again in the wind, and we were concerned about not having it since we could feel some blowing rain, so we gave up the ghost. We packed our stuff up, got back in the car and drove into Alamogordo to get one of the last motel rooms available at that hour of the morning.

The wind blew all night and into the morning hours, and indeed there was some rain. We had not planned to return until Monday, but when we awoke, there were scudding clouds all about and little sun; we decided that wherever we might go to do any hiking we’d have the same conditions, so we reluctantly decided just to head on home. We had breakfast in Alamogordo, and then headed off east along US 82. The drive through Cloudcroft was pretty, but we’d been this way before and already had pictures. We continued along US 82 through Artesia and north of Hobbs and on into Texas. We continued east, finally meeting up with I-20 into Fort Worth. It was a pleasant drive, but not a lot of scenery, so we just listened to music and talked. We had dinner on the east side of Fort Worth, and got home about nine. We were sorry to cut the trip short a day, but these things happen. It was the only camping trip thus far where all our planned nights of camping were cancelled because of weather.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

November 22, 1997: My 51st Birthday |

|

October 11-13, 1997: My Nephew Ted Visits Dallas |

|

Return to the Index for 1997 |