|

June 19, 2009: New Mexico Trip Day 3 |

|

June 17, 2009: New Mexico Trip Day 1 |

|

Return to the Index for Our New Mexico Trip |

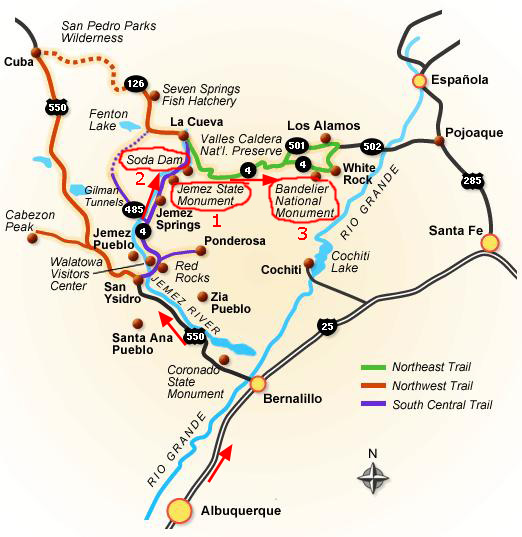

The Jemez Mountain Trail

|

Leaving there, we got on I-25 north towards Santa Fe, exiting on NM Highway 550 to Bernalillo. This highway took us northwest past the Coronado State Monument (which we inadvertently bypassed). The monument includes the partially reconstructed ruins of the ancient Pueblo of Kuaua, a Tiwa word for "evergreen." This monument is named for Francisco Vasquez de Coronado who is thought to have camped near this site with his soldiers in 1540 while searching for the fabled Cities of Gold but instead found thriving agricultural villages inhabited since 1300 AD.

At San Ysidro, we turned north on NM Highway 4, which is actually the beginning of the Jemez Mountain Trail. We did not stop at the Ponderosa Winery; we stopped there with Prudence and Ron on a trip the four of us made out here to Santa Fe some years ago. (I am not sure what year it was, but you can check the year indexes to find it.) We took some pictures along the way, and you can look at them by clicking the thumbnail images below:

|

On the Jemez Mountain Trail: The Jemez State Monument

Introduction

|

Jemez State Monument has not only the ruins of this ancient pueblo of the Giusewa but also the ruins of a 17th-Century Spanish mission known as San Jose de los Jemez. The mission had a unique octagonal-shaped bell tower. There is a museum and signed trail at the Monument, which is part of New Mexico State Monuments.

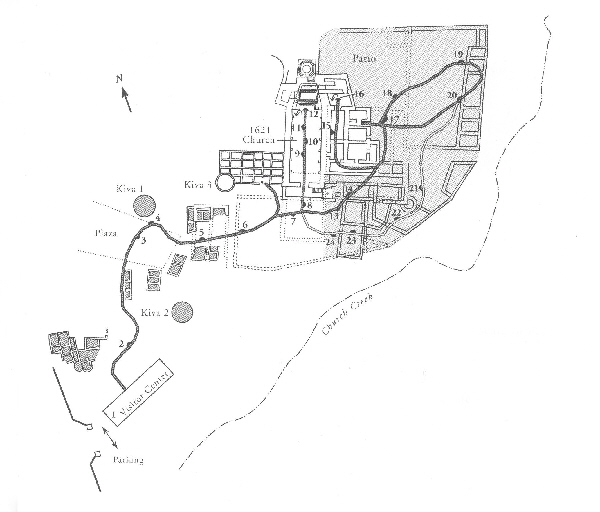

We stopped at the entrance building/museum and paid our entry fee, picked up a trail map and headed out along the relatively short trail by the pueblo and church ruins. We took quite a few pictures here, certainly not all of which will be included here. I have scanned a copy of the trail map, and I will key the pictures I took to it.

The map at left is a bit hard to read, so when we actually get to the pictures, I'll use small sections of the map to illustrate where they were taken. I can magnify these smaller sections so that you can read them.

The Pueblo of Giusewa

|

In the winter of 1540-41 a comet of change fell upon what is now the southwestern United States and forever altered millenia-old patterns of Puebloan living. Francisco Vasquez de coronado and his entourage of soldiers, Franciscan priests and Mexican-Indian auxiliaries set up camp in a village near the present Rio Grande town of Bernalillo and sent parties of exploration throughout the region.

Captain Francisco de Barrionuevo visited seven "Hemes" villages at that time. He reported that the Jemez people were peaceable and furnished provisions to their Spanish visitors. One may wonder how the villagers at Giusewa felt about the newcomers, especially after they heard reports of the Spanish soldiers' harsh treatment of the Rio Grande Tiwa Indians 40 miles away.

The word "Jemez" is a Hispanicization of "Hemish," which means "people" in the Towa language (still spoken at Jemez Pueblo today). "Giusewa" is the Towa word for "place of the boiling waters." Several hot springs are located nearby. today, Pueblo Indians of New Mexico continue to use Towa, Tewa and Tiwa, three branches of the Tanoan Indian language group which are unintelligible among one another.

The Plaza

The plaza was a marketplace where individuals exchanged food or craft items with travelers from other pueblos or from nomadic groups such as the Apache and Navajo. Perhaps, on occasion, native traders who walked freom their distant homes in Baja California or other Mexican regions to trade with the Rio Grande pueblos, brought seashells, colorful macaw plumage and pottery to Giusewa. There is little left of the plaza itself, now. The trail goes right through it, and I took a picture of Fred in the plaza area (with the ruins of the old church in the background).

From here (#3) we could look back down the walkway towards the Visitor Center, and also through the blooming cholla towards the new Catholic church across the highway.

Kiva 1

The flat earthen roof of the kiva, which caved in long ago, was supported by posts crisscrossed by tree branches. On the floor is the opening for a fire pit. A hatchway through the roof above the pit served as an opening for smoke to escape and as a ladder entrance. As warm air ascenced, a ventilator shaft (the small square opening in front of Fred) brought in cool air.

The kiva wall, originally a two-foot-thick mixture of sandstone, basalt and limestone rocks, has intermittently slumped since excavation by the CCC in the 1930s. Monument staff, under the direction of archaeologists, have tried to stabilize and preserve the structure since then.

Evolved Buildings

|

Two Sacred Places

On the left are all that remains of a three-story, apartment-like block of contiguous pueblo rooms that attached to a kiva on the southwestern corner. The features of the kiva are no longer distinguishable. This complex also held a C-shaped altar with four-foot-high adobe walls that enclosed three sides of a fire pit.

The much more massive structures to the right are the remains of the church and convento of Mission San Jose de los Jemez, thought to have been built by a Franciscan priest beginning about 1621. Evidently, the west wall of the monumental second church (seen here with Fred) was built and attached to th eeast edge of the pre-existing pueblo complex. Such a building sequence suggests that whoever designed the 1621 church made careful measurements to fit it in between the pueblo rooms on the west side and the mission rooms constructed twenty years earlier on the east.

The 1621 Mission Church

|

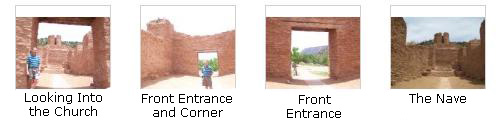

After a 1623 fire, a new, 2-story facade was added onto the church south of the original front wall; this addition had a new choir loft. Other additions were a small side chapel to the left of the front entrance and a baptistry to the right. Nothing of these additions remains today. Here is a view of the church entry taken from stop #8.

Below are thumbnail images for more views of the nave taken at stops #9, #10 and #11; click on them to view the pictures:

|

Of course, the church had a roof at one time but, being made of wood, it has long since disappeared. To allow light to flood into the church, illuminating the frescoes, statues and religious objects, large clerestory windows were built high into the walls of the nave and sanctuary. These may have been covered with hides or a translucent material called selenite during the winter.

Below are some thumbnail images for pictures that we took inside the ruins of the church, either of the altar area or on or around it. You can click on these thumbnails to view the full-size pictures:

|

The Convento

|

Closer up to the north end of the church, you can see the sacristy, friar's chapel and the bell tower. The visitor trail continues to the courtyard (patio) and the far corner of the convento, which you can see as you look up the trail. In this area of the convento, which was actually a walled compound that would have been defensible, vegetables and fruit trees were grown; corn, beans and squash were probably cultivated in the valley below. Wild game supplemented the dairy products and meat that mission cows, goats, sheep and pigs provided.

There were many other ruined rooms, including a pantry and storerooms, and we took a number of pictures. If you will click on the thumbnail images below, you can have a look at them:

|

We returned to the visitor center along the first part of the path, and spent a bit of time in the museum. We have learned that the accrued information about San Jose de los Jemez is still incomplete, hazy, confusing, sometimes contradictory and continually changing. But the research continues into the history of this important settlement, which seems to have been abandoned by the early 1690s.

On the Jemez Mountain Trail: The Soda Dam

|

Apparently, there was a vein of harder rock here and at one time there must have been a small lake behind it. A combination of intermittently great water volumes and erosion eventually formed a tunnel through the rock (or a spillway around it). The result is that the river flowing down from the north hits the hard rock vein and is diverted to the opening you can see at the right, forming a waterfall on the southern side of the rock vein.

The waterfall empties into a relatively deep pool that is ideal for swimming, and on weekend days in the summer this place is extremely crowded. This is the fourth time that Fred and I have stopped here at the Soda Dam. We were here once before by ourselves, once with Ron and Prudence and once with Greg. You may already have seen pictures from all those occasions here in this album. From the pool, the Jemez River continues downstream alongside the road, and you can see two views of the river below Soda Dam here and here.

We made three movies here at Soda Dam.

|

This movie was taken from below the dam, and shows the natural rock dam and the waterfall formed by the water flowing around and through it. |

When we climbed up and over the top of the dam to get to the upstream side, Fred made a movie showing the upstream side of the dam and the Jemez River disappearing into the hole through the rock. |

|

I filmed the third movie from a perch on a large rock out in the middle of the Jemez River; I wanted to concentrate on the flow of water down and around me and then through the dam. |

We took some other interesting pictures here at Soda Dam, and if you will click on the thumbnail images below, you can have a look at them:

|

Driving to the Tsankawi Ruins Trail in Bandelier National Monument

|

Highway 4 continues eastward through the Jemez Mountains, eventually passing to the south of Los Alamos, NM, and continues to the entrance to Bandelier National Monument. We wanted to stop and get a campsite before the day got too late, although the young lady at the entrance station told us that the campground would have plenty of spaces. We drove into the Juniper Campground, which was just beyond the entrance station, found a good site, paid our fee to reserve it, and then headed off to do our first hike at the Tsankawi ruins in White Rock, NM.

In Bandelier National Monument: The Tsankawi Loop Trail

Introduction to the Tsankawi Ruins

|

Just before the junction, we found the parking area on the right-hand side of the road.

In the 1400’s, Tsankawi was home to the Ancestral Tewa Pueblo people. Today their descendents live in nearby San Ildefonso Pueblo. The Ancestral Pueblo people built homes of volcanic rock and adobe (mud), cultivating fields in the open canyons below. Their daily lives of hard work and family left their mark on the land. Low stone walls, carved drawings in the rock faces, and fragments of utilitarian objects are important artifacts left by the Ancestral Pueblo people. For the people of San Ildefonso Pueblo these sites represent much more than interesting glimpses into the past. Although the present-day Pueblo people do not occupy Tsankawi on a daily basis, the site serves an important role in their spiritual lives and provides both tangible and intangible connections with traditions passed down through generations. Tsankawi is a timeless place where echoes of a distant past intersect the present. Parents raised children here. Together they fought the ravages of nature to survive in these now vacant rooms and along these dusty trails.

Our Walk Through Tsankawi

|

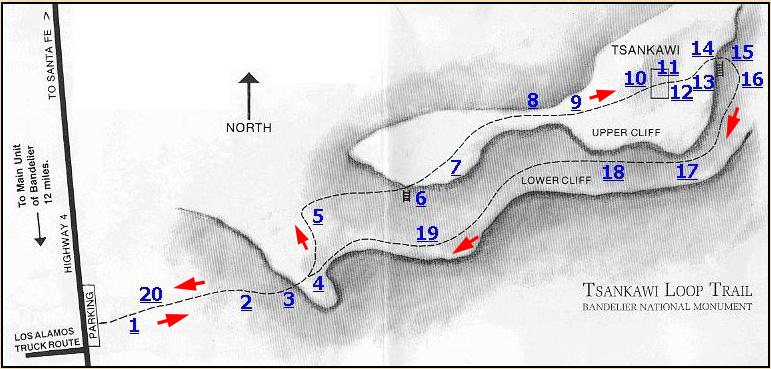

Here is the trail map that we found in the trail guide that we carried with us. On the trail map, you can find twenty underlined numbers; these are the various marked trail stops. To follow us along the trail, just click on the numbers in any order you wish. When you do, you'll be taken to the description of that trail stop. When you are done with that trail stop, you will find a link that will bring you back here- or you can just scroll on down to the next stop.

When you are done with all the trail stops that you want to look at, and are ready to go to the next activity today, please click here.

|

|

The prehistoric people of Tsankawi (sah-kah-WEE) were totally dependent on their environment. Everything they possessed - their homes, clothing and food - came directly from "Mother Earth". After many years of occupancy they moved on. Although they respected the Earth and her gifts, they had to use some resources in order to stay alive. In this sparse, arid environment, their needs were too great to be sustained indefinitely. Archaeologists tell us that the ancestral Pueblo people left Tsankawi as a result of a decrease in rainfall, along with the depletion of important natural resources such as firewood, and soil exhaustion from centuries of farming. Many Pueblo Indian legends tell of groups moving from place to place. Moving on after several generations may have been an expected part of life.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

Juniper, pinon, rabbitbrush, yucca, four-winged saltbush, and mountain mahogany are common along this trail. Ancestral Pueblo people depended on many of these plants for food, medicine, dyes, spices, and tools. Some of these plants are still used for the same purposes in contemporary pueblos.

The climate has changed little since the time when Indians were living here. The environment is dry, averaging about 15" of precipitation each year, and frost or freezing can occur into mid-May. Yet these people were able to develop an agricultural way of life. They made expert use of resources such as native plants, wildlife, and various types of stone.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The type of plants here are typical of pińon-juniper woodlands found in many areas of the Southwest where ancestral Pueblo people settled. Plants adapted to dry conditions are usually slow-growing and not very tall, thus the name "pygmy forest". Ponderosa pines, common at higher, wetter locations, are usually found only near arroyos (drainages) where more moisture is available. Along the trail are juniper, pińon, rabbitbrush, yucca, saltbrush, mountain mahogany, and other plants that the people depended on for food, medicines, dyes, spices, and tools.

Just beyond this trail stop, we encountered our first ladder, and I took a picture of Fred climbing up it.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The trail split at this point when we climbed the ladder, and I made a movie at the top of it. You can watch that movie using the player below:

|

Stop 4 This movie was made at the top of the ladder. |

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

Many sections of the trail we were following were worn 8 to 12 inches into solid rock. Throughout the Pajarito Plateau there is a network of similar trails, often connecting villages or leading to farming areas. They were cut and worn into the rock by generations of ancestral Pueblo people, barefooted or in sandals, passing back and forth from their mesa-top homes to the fields and to springs in the canyons below. Walking barefoot or in sandals along these routes from their mesa-top homes to the fields and springs in the canyons below wore even deeper impressions into the soft stone. Present-day visitors with hard-soled shoes cut the trails even deeper. Erosion adjacent to these early trails became a major problem as people avoided walking in the waist-deep trenches. A project in the late 1990’s used fill material to repair the badly worn trail.

|

In the 1940’s the United States government needed a site for top-secret scientific research. The Pajarito Plateau with its deep-cut canyons was difficult to access and easy to secure making a perfect place for a government installation during World War II.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The petroglyphs here are only a few of many along this cliff. You can see three human-like figures, bird designs, four-pointed stars, and other symbols. The large figure appears to have cornhusks or feathers on top of its head. Petroglyphs are common throughout this area and much of the American Southwest. Meanings of some are still know to present-day Indians. Because they are carved into soft tuff, even touching these petroglyphs can cause permanent damage.

|

To the right are some thumbnail images for the pictures we took here at the first group of petroglyphs at stop #6. Click on them to look at the full-size images.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here.

|

Imagine living in this dry, open land. In the winter, an icy wind blowing from the mountains above could pelt you with bits of frozen snow forcing you to seek shelter in the protection of the cavates, such as in the small man-made caves carved into the soft tuff that are found at Stop #15. In spring, the lengthening rays of the sun would herald the beginning of the time to plant. In summer, you might closely watch the western mountains as towering clouds form and build hoping they bring the necessary rainfall to make your carefully tended crops grow. In autumn, the slopes of the Jemez Mountains would be colored with the gold of turning aspens, a sure sign the cold days of winter would soon return. You would want to make certain you had plenty of food in the storage rooms to supply your needs through the long winter.

Why did the people choose this and other similar mesa-top locations for their homes? The lack of soil here may be due to heavy livestock grazing in the 1800s. In the 1400s the mesa-tops may have been more likely places for farming than they are now. Some of the fields of corn, beans, and squash could also have been located in the canyons below to take advantage of runoff. Today, there is no permanent source of water here. Prior to the development of the modern community of Los Alamos, there may have been a permanent stream to the north in Los Alamos Canyon. Mesa-top dwellers would have had to use pottery jars to carry drinking water from the stream, or store rainwater in structures like the ones you will see at marker 14. Mesa-top locations may have been chosen for defensive reasons, but there is no evidence of warfare or strife. Perhaps there were other reasons for which we have no evidence.

Here is a good view looking along the edge of the mesa.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

|

I also made a movie from this stop on the trail, and you can watch it using the player below:

|

Stop 8 This movie shows the scenery from here on top of the mesa. |

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The people who lived at Tsankawi were not isolated. Many other villages were located on nearby mesas and in canyon bottoms. People of various settlements probably traded tools, pottery, blankets, agricultural products, feathers, turquoise, and seashells and joined together for social and religious activities. They were all competing for the resources of the area, especially game and firewood. An enterprising hunter who tried to find more deer and rabbits by travelling far from his village would soon be approaching another. A trip to the mountains might be more successful, but the meat would have to be brought back- a long carry in a time when horses were not available.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The large settlement had about 350 rooms. Like Tyuonyi in Frijoles Canyon, the structures here were one to two stories high. Unlike Tyuonyi, there has been minimal excavation in this village. After the Ancestral Pueblo people moved from here the elements took their toll on the stone masonry of the pueblo. With passing time, roofs caved in and winds covered the walls with dirt. Plants, such as four-wing saltbush and snakeweed, which prefer disturbed soil, followed further obscuring the pueblo. The layers of soil, roots, and rock actually protect the buried site. Actually, were it not for the identifying signage, one would hardly know a pueblo had been here.

The settlement was roughly rectangular in shape and enclosed a large central courtyard or plaza. Everyday living activities occurred in the plaza along with various dances and ceremonies. The architectural plan of room blocks surrounding a central plaza is still used in the villages of present-day Pueblo Indians. The rooms were constructed of tuff blocks, shaped using harder stones and then laid-up with mud mortar. Walls were then plastered inside and out. Roofs were made of wood and mud. Archaeological evidence indicates Tsankawi was probably built during the 1400s and inhabited until the late 1500s. Archaeologists refer to this time as the Rio Grande Classic Period. Local people left the many small villages throughout the area and moved together to build large pueblos such as Tsankawi.

Although excavation was a technique commonly used by early archeologists, it is not used at Tsankawi and the rest of Bandelier today. Of the Bandelier’s almost 3000 recorded archeological sites, very few have been excavated. Consultation with San Ildefonso Pueblo has revealed that they prefer that the homes and belongings of their ancestors remain untouched. Using new archeological technology a variety of information can be gathered from an archeological site without ever uncovering it. Here, as elsewhere, discovered pottery shards have simply been left in small piles for visitors to see.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

The villagers had a spectacular view of their surroundings. To the west are the Jémez Mountains. To the east are the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) Mountains and the Espańola Valley. About 70 miles south are the Sandia (watermelon) Mountains, just east of present day Albuquerque. This entire area is part of a major geolgic feature, the Rio Grande Rift, which the Rio Grande River flows through. Along its banks live the descendents of the people from Tsankawi and other nearby villages.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

Tsankawi was abandoned in the late 1500s; why is still a mystery. Traditions at the modern pueblo of San Ildefonso, 8 miles to the northeast, say that their ancestors once lived in Tsankawi and other nearby pueblo sites. From tree-ring evidence we learn there was a prolonged dry period during the late 1500s. The lack of rain, combined with growing crops in the same fields for generations, may have brought about crop failures. There may have been other reasons for the abandonment too, but until further research is done, the mystery will remain.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

Why did the village have so many rooms? Being farmers, the people would have needed plenty of space for storage of dried corn, beans, and squash. The food they stored had to provide for their needs not only for the present year, but also for times when there were crop failures. Other rooms would have been used for cooking and sleeping, and special chambers (know by the Hopi term kiva) were used for gatherings for religious and other purposes.

Today there is no permanent source of water at Tsankawi. Prior to the development of the modern community of Los Alamos, there may have been a permanent stream in the canyon to the north. Having a reliable source of water nearby would have been very important to the people living at Tsankawi. Although there is no evidence of warfare or strife here, mesa-top locations may have been chosen for defensive purposes and for enhanced communications with nearby villages.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

Like in Frijoles Canyon, the people here took advantage of the benefits of building stone structures against south-facing walls. Most of the caves carved into the stone wall to your right had small masonry buildings, known as talus pueblos, constructed in front of them. The thick stone walls exposed to the direct rays of the sun capture and radiate heat in the winter keeping the buildings and cavates much warmer than the exterior air. Small fires may have also been used. In the summer the walls insulate the stone rooms keeping them somewhat cooler than the exterior air. These buildings would have also offered protection from the onslaught of afternoon rainstorms.

Most of the caves carved into the soft tuff cliff had small masonry buildings, known as talus pueblos (talus is the loose stone at the base of a cliff), constructed in front of them. These buildings have long since collapsed. Often the only remaining evidence of them is the socket holes where roof timbers were anchored. Try to imagine what it might have been like to be cooped up inside these small rooms during long, cold, snowy winter nights with a smoky fire for light and heat- summer must have been welcome! All the nearby mesas have cave rooms on the south-facing side- a real advantage in winter. The afternoon sun would warm the cliffs, melt the snow, and allow the people to spend at least a few hours outside on sunny days. By contrast, the north-facing slopes often retain their snow cover throughout the winter.

|

I made a movie at this stop and you can watch it with the player below:

|

Stop 15 This movie was taken inside one of the cavates- the shelters carved out of the tuff. It will show you what the cavate was like inside- how big it is and how it was arranged. |

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

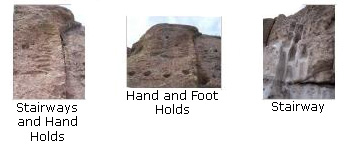

At right are three thumbnail images for the pictures we took here of these stairways and hand-holds. Click on the thumbnails to view the full-size images:

|

|

Standing here surrounded by the caves, canyons and mesas, imagine how different the area was when inhabited. Most caves would have had one or more small, square, smoothly plastered rooms in front. Most of the nearby trees would have been cut for roof beams, tools, or firewood. The canyon bottoms would have been covered with agricultural fields. Around you would be all kinds of activities - women cooking, sewing, grinding corn; men tending the farms or making tools; children playing. The sounds of people singing and children, dogs, and turkeys chasing each other would have filled the air, along with smoke from household fires and the smells of cooking, meat drying and many people living in close quarters. It would have been a lively busy scene, far different from today's atmosphere of quiet and solitude.

Fred is very interested in petroglyphs and pictographs; we have taken numerous pictures of them all over the American Southwest, and here is no exception. I have put thumbnail images for a large selection of these pictures below; click on them to view the full-size images:

|

So to make it easy for you to go through these pictures, I've put them in a slideshow.

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at right and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

If you look carefully as you go along the trail, you will see many more petroglyphs on the cliffs. Depending on light conditions, some may be obvious. Others may be faint and hard to see.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

|

|

|

The National Park Service hopes that you have enjoyed your visit to Tsankawi. You have explored only a small part of Bandelier National Monument. We invite you to visit the main section of the monument, which is 12 miles south on State Road 4. The Visitor Center, monument headquarters, and a self-guiding trail are located in Frijoles Canyon. Park rangers are on duty to answer questions and help plan your visit, and an introductory 10-minute slide program is available. During summer, interpretive activites may be offered. The museum contains exhibits on the continuing culture of the Pueblo people.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking

here.

In Bandelier National Monument: The Falls Trail

Getting to the Trail / Introduction

|

|

|

On the Tsankawi Trail, it was pretty easy to match up the photos we took with the stops on the trail; we took pictures at most of them. On this trail, though, while we read the trail guide as we walked along, we only took pictures at some of the major points. So I won't use the same technique of individual sections for each stop on the Falls Trail, like I did earlier for Tsankawi. But I do think the trail guide had a lot of interesting information, so I am going to include the narrative from it here in the photo album, and try to place groups of our pictures every so often when they illustrate items of interest from the trail guide.

I hope you enjoy the trail guide sections.

Hiking the Falls Trail

|

I took a movie shortly after we started out on the trail, and you can watch that movie with the player below:

|

Starting Out It is just after 5PM and we are starting out on the Falls Trail in Bandelier NM. I took this movie to record the event. |

|

|

|

|

|

Below are some thumbnail images for the pictures we had taken up to this point. You can click on the individual thumbnails to view the full-size pictures:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below are thumbnail images for the best of the pictures that we have taken here on the Falls Trail over the last few guidebook stops. To view the full-size pictures, just click on the thumbnails:

|

|

|

|

|

I also took a movie here and you can watch it with the player below:

|

Stop 16: The Upper Falls We have reached the Upper Falls here on the Falls Trail in Bandelier NM. This movie will show you what we saw of the Upper Falls from our vantage point on the trail. |

|

|

|

|

|

From the lower falls overlook, we could look ahead down Frijoles Canyon all the way to the Rio Grande off in the distance.

I also took two movies here at the lower falls, and you can watch those movies using the players below:

|

|

At this point, it was getting a little dark in the canyon, and we decided not to hike the last mile down to the Rio Grande River. We thought this might put us back at the campsite a bit late to do our cooking and get everything set up. So we decided to just walk down a bit further along the trail that hugged the canyon wall just because it looked interesting. Then we stopped and I made a final movie of the trail ahead before we turned around to head back. You can watch that movie using the player below:

|

Stop 19 This movie was taken at the point where we decided not to hike all the way down to the Rio Grande but rather to return to the campsite. |

But since I have shown you the trail guide up to this point, I should probably show you the last three stops- just to complete the picture for you. These last three stops are below.

|

|

|

So we've turned around and begun hiking back up the trail to the visitor center. Along the way, we took some additional pictures that I want to include here, and I have put thumbnail images for them below. If you will click on these thumbnails, you can view the full-size pictures:

|

At the visitor center, we got back in the RAV4 and headed off back up the park road to the Juniper Campground near the park entrance.

In Bandelier National Monument: The Juniper Campground

|

In the morning, before we took the tent down, we took a couple of pictures of the campsite. Even though these pictures weren't taken today, I'm going to include them here anyway. Just click on the two thumbnail images at left to have a look at these two pictures.

You can return to the page index

or use the links below to go to another album page.

|

June 19, 2009: New Mexico Trip Day 3 |

|

June 17, 2009: New Mexico Trip Day 1 |

|

Return to the Index for Our New Mexico Trip |