|

May 27, 2017: Karlstein Castle; Troja Palace; Prague Botanical Garden |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |

On Friday morning, Fred and I checked out of the Hotel Am Steinplatz and made our way to the main train station- the Berlin Hauptbahnof. In addition to being the main transfer point for most of the trains we took around Berlin during our visit, it is the departure point for the trains that go elsewhere in Germany and to destinations all over Europe- including Prague.

The Trip to Prague

|

At the station, we once again took the familiar train heading north and then east around the center of Berlin. The Berlin Hauptbahnof, Berlin's main train station, is right on the River Spree in pretty much the center of town. (This seems to be true of most European main train stations- they are conveniently located in the center of the towns that they serve. There will be other train stations, of course, for local trains. But the intercity trains will all arrive at and depart from these central stations, which are always easy to get to.)

Here at Hauptbahnof, the local trains are on the top levels of the station, and their tracks run basically east-west. The intercity trains are on the lowest level, and it seemed that their tracks ran basically north-south (although I am pretty sure that there are some intercity trains that use the tracks on the upper levels.

Anyway, I wasn't sure of this layout when we got off the train from Zoo Station, but another nice thing about trains, trams, buses, and trolleys in Europe is that the signage is very clear. Once we came down from the upper platform, finding our way to the intercity trains was very easy, and once we got down to their tracks, finding the right track for the Prague train was also pretty much foolproof. We were at the platform for our train well over an hour early; I didn't want to run the risk of missing the train because of some delay, so we left the hotel a lot earlier than we really needed to. Here are a couple of pictures taken on our platform on the lowest level of the Hauptbahnof:

|

|

You have already seen, in the pictures from our stay in Berlin, how big Hauptbahnof actually is; it is also very modern. Berlin Hauptbahnhof, the city's main station, came into full operation two days after a ceremonial opening on 26 May 2006. It is located on the site of the historic Lehrter Bahnhof, and is one of four "Category 1" stations in Berlin (such stations being main transfer points between local and intercity trains).

|

Lehrter Bahnhof opened in 1871 as the terminus of the railway linking Berlin with Lehrte, near Hanover, which later became Germany's most important east-west main line. In 1882, with the completion of the Stadtbahn (City Railway, Berlin's four-track central elevated railway line, which carries both local and main line services), just north of the station, a smaller interchange station called Lehrter Stadtbahnhof was opened to provide connections with the new line. This station later became part of the Berlin S-Bahn. In 1884, after the closure of nearby Hamburger Bahnhof (Hamburg Station), Lehrter Bahnhof became the terminus for trains to and from Hamburg.

Following heavy damage during World War II, limited services to the main station were resumed, but then suspended in 1951. In 1957, with the railways to West Berlin under the control of East Germany, Lehrter Bahnhof was demolished, but Lehrter Stadtbahnhof continued as a stop on the S-Bahn. In 1987, it was extensively renovated to commemorate Berlin's 750th anniversary. After German reunification it was decided to improve Berlin's railway network by constructing a new north-south main line, to supplement the east-west Stadtbahn. Lehrter Stadtbahnhof was considered to be the logical location for this new central station- Berlin Hauptbahnof.

One often hears of autocratic rulers that "at least they make the trains run on time". Well, Germany has no autocratic ruler, but the trains run on time anyway. Our intercity EC train to Prague arrived at the indicated platform well ahead of its scheduled departure time, and it left exactly on time.

|

|

So we picked a compartment that already had two young girls occupying the window seats; it was the least crowded of all the compartments, and as it turned out, not only was the window large enough that taking pictures was no problem, but the girls- medical school students from Australia doing some of their coursework in Europe- were engaging and friendly. They spent some of the trip working on their job applications for their return home, but also took the time to converse with Fred and I about a number of topics. They, like Jeffie tells us that Czechs in Prague, wanted to know what the heck was going on in America politically, and much of our conversation was directed to that topic.

For the first half of the four-hour trip, the portion that took us through Dresden and into the Czech Republic, the train passed through typical countryside, and we took quite a few pictures. Most of these were just of farms and little towns, and perhaps not all that interesting, but here are two views from southern Germany between Berlin and Dresden:

|

|

During our previous week in Berlin, the six of us had made a trip to Dresden; today, the train went through that city again. Here, I made a film as we went through town; we were on an express train to Prague, so we didn't stop.

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

We left Dresden behind, and the train moved again out into the countryside. About forty minutes later, the train came alongside the Elbe River, and for most of the rest of the way to Prague we had that waterway in view. I made one movie from the train as we passed along the Elbe, and there is a player below, left, for that movie. Below, right, is a slideshow for some of the best of the pictures we took during our time along the river; as usual, use the buttons in the lower corners of each image to move through the show.

|

|

A few miles north of Prague, the train swung away from the river and headed more directly south towards the city. The countryside north of Prague reminded me of nothing so much as the high country of Southern Colorado- verdant valleys surrounded by mountains.

Praha hlavní nádraží: Prague's Main Railway Station

|

The Art Nouveau station building and station hall were built between 1901 and 1909, designed by Czech architect, Josef Fanta, on the site of the old dismantled Neo-Renaissance station. The station was extended by a new terminal building, built between 1972 and 1979, including an underground metro station and a main road on the roof of the terminal. The new terminal building claimed a large part of the park, and the construction of the road cut off the neo-renaissance station hall from the town. In 2011 a partial refurbishment of the station was completed by an Italian company Grandi Stazioni, which had a 30-year lease on much of the retail space in the station. Last year, the company lost its concession after failing to complete the renovation of the historic building by the extended contractual deadline.

We didn't know about the art nouveau touches until we'd walked through the tunnel between the platforms and the station building and came under the rotunda that you can see in the aerial view above. We could look up at the beautiful decoration on the level above us and underneath the dome, and we began taking some pictures. In the pictures in this section, the ones that appear to be looking up into the dome area were taken as we arrived in Prague; the others were taken on our return to the station so we could go up to the dome level and look around.

|

The decorative elements were pretty interesting, and I thought that the color choices and some of the designs were reminiscent of American Indian designs, but obviously were not intended to be so. Here are clickable thumbnails for some of the better views:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Part of the design of the art nouveau station were the stained glass windows.

|

This station was so very different than Berlin's Hauptbahnof because is was so very much older. I thought that the Czechs had done an excellent job of taking an historic building and updating it rather than replacing it.

|

And below are clickable thumbnails for more view of the decorative elements used here in the station:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Meeting Jeffie and Getting to the Fortuna West Hotel

|

|

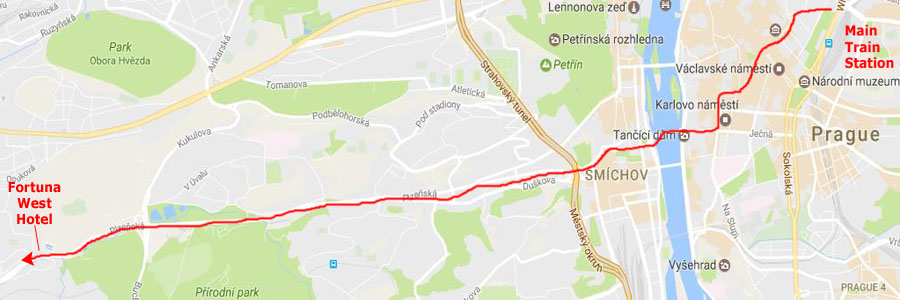

Our first experience with the transportation system in Prague would be our trip to our first night's hotel- the Fortuna West Hotel about four miles west of Prague just off the #10 tram line. At the tram stop beside the main train station, Jeffie taught me how to read the posted tram and bus schedules, and how to determine which side of the mid-street tram platform we needed to be on to get a tram going in one's desired direction. Fred took a couple of pictures while I was getting this instruction:

|

|

Jeffie's explanations were very understandable, mostly because the signage for trains, trams, and buses is very logical and intuitive. For example, once you determine the name of your destination stop (and the Fortuna West had supplied the name of the tram stop quite near them), you find that name in the list of stops for one or more of the numbered lines that are on the sign (and all the numbered routes that stop there are listed on the signage). You can take any tram line where your stop appears.

|

|

The tram first wound its way through some of street in downtown Prague to a major street that crossed the river Vltava heading west. Our hotel was about four miles from the train station in a suburban area.

|

This hotel looked pretty good, particularly as it was located on a main tram line, and it did turn out to be an OK place to stay except for one thing- it wasn't air-conditioned. For most of the year, this wouldn't be much of a problem, but this week Prague was a bit warmer than usual. Opening the windows helped a great deal, but a side effect of being convenient to the tram was that the hotel was also near the major street where the tram line was, and so there was considerable traffic noise.

This made it a bit difficult to sleep, but since it was only for one night, we could live with it. On the plus side, the hotel included breakfast with the room.

We got checked in and dropped our stuff in the spacious room and then got ready to head back out with Jeffie to do some walking around Prague for the remainder of the afternoon. On the way back to the tram, I took a few pictures that you might find interesting:

From the top of the sloping walkway up to the Hotel Fortuna West, this view looks toward the center of Prague. |

This view looks down the sloping walkway to the tram stop. That's a bus heading towards the center of Prague, not a tram. |

We are at the tram stop, and here comes a tram heading back into town. (I was surprised by how frequently all the forms of transportation ran.) |

I just took the opportunity of being on an uncrowded tram to take a picture to show you what a typical one looked like inside. |

An Afternoon Walk in Prague with Jeffie

|

Even this early in our stay in Prague, I was becoming more and more impressed with the public transport in the city. A quick look at the subway, tram, and bus map I picked up at the Hotel Fortuna West seemed to show that there weren't many areas more than a couple of blocks from some element of the local transportation system, and the transport ran frequently enough that it seemed that having a car in Prague would be unnecessary.

|

|

The foundation stone for the new church was laid down in 1881, and the church was completed four years later. The ceremonial consecration of the church was carried out by the Archbishop of Prague, Bishop Schönborn, with the assistance of the Prague Holy Roman Catholic Bishop Karel Schwarz and Bishop Martin of the Bohemian order. The parish status was transferred to the church and the original parish church demolished in 1891.

On Sunday September 27, 2015, the skull of St. Wenceslas (which, along with its crown were borrowed from the Cathedral of Saint Vitus, Wenceslas and Vojtech at Prague Castle, was exhibited at this church for the first time.

We got off our tram in a district known as Andel, and we began walking towards a restaurant that Jeffie knew of where we could get typical Czech fare for supper. Here is a typical street scene on the way to the restaurant- Koslovna Lidicka.

|

Jeffie was right; this restaurant seems to be a popular destination for people seeking excellent Kozel beer and first rate Czech cuisine. Jeffie had told us that even though there are lots of cafes and restaurants in Prague, evening reservations are usually a good idea, but when she called the restaurant from our hotel, they said there were no tables for 6PM. Again, Jeffie knew something of how things work, and she was pretty sure that if we just dropped in, we would probably find a table without too much problem. When we came in, a good many tables had little "Reserved" signs on them, but there were a fair number that didn't, so we were fine.

The menu leaned heavily towards traditional Czech cuisine, although there was a burger or two available. We opted for Czech food which, in my case, was a goulash and in Fred's case a bone-in cut of pork. (Oddly, given the decor in the restaurant, I did not see an entree labeled as goat, but I could have missed it.) Jeffie, of course, had a vegetarian dish.

Jeffie and Fred had beer, while I stuck with water. Unlike American restaurants, when you order just water in Europe you are served bottled water; while it isn't free, as it is here, it costs relatively little. The one thing I always had to ask for, though, was ice. Our entrees were served in miniature roasting pans, and were quite good.

When we were done with dinner, we continued walking east towards the river, arriving at and walking across the Palackeho Most ("most" being the Czech word for "bridge"). It was a beautiful evening, and we took lots of good pictures on the bridge.

|

|

The Palacký Bridge (in Czech "Palackého most") was built in 1876 and is currently the second oldest functioning bridge over the Vltava River in Prague. The only bridge that is older and still in use is the famous Charles Bridge, which we plan to visit during our stay. On this beautiful afternoon, the two panoramic pictures I took from the bridge turned out well. The first one, featuring my niece, Jeffie, looks upriver (south) and in the distance you can see the spires of the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul on the grounds of Vysehrad Castle (another place we will visit this week):

|

In my second panoramic view, we look both upriver to the right and downriver to the left. The bridge to the north (downriver) is the Jirásek Bridge and the one to the south is the Zeleznicki Bridge, which is exclusively for trams and pedestrians:

|

The views from the bridge were really impressive, and Fred and I took quite a few pictures, whittled down here to four different views.

This view, showing the southeast side of the Vltava, shows the quay that runs along the city side of the river. On the quay, which Jeffie says is often crowded on nice evenings, you can see the docks where both public and private craft are docked. |

Looking at the northeast side of the river, you can see some of the interesting new architecture that has become blended with the much older buildings in Prague- especially that whimsical building that seems to be leaning. |

Among the other photos we took from the bridge, a notable one was a closeup view of the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul at the Vysehrad Castle on the hill to the southeast. We visited this church on our last full day here in Prague, and it was one of the two most impressive we saw in Prague.

|

In 1588 the construction of the present tower started, and it was completed in 1591. The tower and the water-station, which was situated on the north side of the tower, were built with the help of a wooden crane. Besides the crane the carpenters also constructed eight water wheels to drive the machinery. Documents mention that in 1601 this water-station supplied 3/4 of New Town with water. The water-station was named after the miller, Jan Šítka, who owned the nearby mill.

The tower was damaged by the Swedish army during the 1648 siege, an event commemorated by a cannonball that is still stuck in the wall of the tower. Repairs, funded by Emperor Ferdinant, were carried out in 1651, at which time the tower gained its current Baroque roof, which was covered with copper plate in the 18th century.

The tower served as the water-tower for public fountains and residential houses in parts of New Town and Old Town for a long time. It was taken out of service in 1881 when the new reservoir at Karlov was opened. The waterworks mechanism was taken out in 1882, but the tower was saved from being demolished by the city historical commission, and was thoroughly reconstructed in 1883. The tower actually began leaning much earlier, so in 1927 and 1985, restoration efforts were carried out to stabilize the structure. Another complete restoration of the 140-foot-high tower was performed in 2008. In case you are curious, the degree of lean of the tower is a little more than one-half of one degree. For comparison, the Leaning Tower at Pisa currently leans about 4 degrees, so the lean here is hardly noticeable.

|

The Palacký Monument

|

|

|

Palacký, though entirely national and Protestant in his sympathies, was careful to avoid an uncritical approbation of the Reformers' methods, but his statements were held by the authorities to be dangerous to the Catholic faith. He was compelled to cut out parts of his narrative and to accept as integral parts of his work passages interpolated by the censors. The Revolution of 1848 forced the historian into practical politics. He was at this time in favor of a strong Austrian empire, which should consist of a federation of the southern German and the Slavonic states, allowing the retention of their individual rights. But the collapse of this federal idea in 1852 led to his retirement from politics.

He continued to advocate for Bohemian self-government, and he returned to politics in 1871, and became the acknowledged leader of the nationalist-federal party, which sought the establishment of a Czech kingdom that should include Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. He brought into a coalition even the conservative nobility and some extreme Catholics. He continued to write and speak for independence until his death in 1876. Palacký is considered as one of the three Fathers of the Czech nation; the other two were the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV and the first President of Czechoslovakia Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

I am not sure of the meaning of the sculpted figures on the monument (save for the image of Palacký), but the figures were certainly heroic, as you can see here.

The Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius

|

The story of the operation begins with the identification of Heydrich as the target. He had been appointed the de facto dictator of the areas of Bohemia and Moravia in 1941, to replace a relatively lenient predecessor. He came to Prague to "strengthen policy, carry out countermeasures against resistance", and keep up production quotas of Czech motors and arms that were "extremely important to the German war effort". He ruled with brutal efficiency, and was referred to as "the Butcher of Prague".

By late 1941, the exiled government of Czechoslovakia, under pressure from the Allies, determined that something had to be done to strengthen Czech resistance to the German Reich; brutal Nazi policies had effectively broken the will of the Czechs during the previous two years. The resistance was active in other countries, and the exiled government needed to both interrupt the flow of materiel being produced by the Czechs and inspire the population to make German occupation more difficult. A high-profile assassination would be the method, and Heydrich the target.

|

On 27 May 1942 at 10:30, Heydrich was intercepted as his car rounded a tight curve on his commute to Prague Castle. Gabcik stepped in front of the vehicle and tried to open fire with his Sten submachine gun, but it jammed. When Heydrich ordered his car stopped so he could shoot Gabcik, Kubiš threw a modified anti-tank grenade at the vehicle. Even though it failed to enter the car itself, the explosion still severely injured Heydrich. Gabcik and Kubiš also fired at Heydrich with their pistols but failed to hit him. Heydrich and his driver attempted to chase the two soldiers, but both escaped to a local safe house, not knowing that Heydrich had been seriously wounded.

Heydrich was taken to the emergency room at Bulovka Hospital; he had suffered severe injuries and doctors tried to remove the shrapnel fragments. Operations to repair the other damage were complicated but appeared to be successful, but Heydrich developed a high fever. Seven days later, his condition appeared to be improving, but while eating a meal he collapsed and went into shock. He spent most of his remaining hours in a coma and died on the eighth day after the attack.

|

On June 17, one safe house, occupied by the Moravec family, was raided. Marie Moravec was allowed to go to the toilet, where she bit into a cyanide capsule and killed herself. Her husband was unaware of her involvement, but he and his son were taken to the Petschek Palace for interrogation. The 17-year-old boy was tortured throughout the day but refused to talk. When the Nazis threatened to torture his father in front of him, his willpower snapped and he told the Gestapo where the assassins were hiding. His entire family was eventually executed.

SS troops laid siege to the church the following day, but despite an overwhelming manpower (750 soldiers) and firepower (machine guns, submachine guns and grenades) advantage, they were unable to take the paratroopers alive. Kubiš and others were killed in the prayer loft after a two-hour gun battle. Gabcik and others committed suicide in the crypt after it became obvious that the cause was lost. The original informant confirmed the identity of the dead Czech resistance fighters, including Kubiš and Gabcik.

Bishop Gorazd took the blame for the actions in the church, in an attempt to minimize the reprisals among his flock, and even wrote letters to the Nazi authorities, who arrested him on 27 June 1942 and tortured him. On 4 September 1942, the bishop, the church's priests, and senior lay leaders were taken to Kobylisy Shooting Range in a northern suburb of Prague and shot by Nazi firing squads. For his actions, Bishop Gorazd was later glorified as a martyr by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The assassination of Heydrich was one of the most significant moments of the resistance in Czechoslovakia. The act led to the immediate dissolution of the Munich Agreement (called the "Munich diktat" by the Czechs) signed by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany's ally Italy. The UK and France agreed that, after the Nazis were defeated, the annexed territory (Sudetenland) would be restored to Czechoslovakia. The betrayer Karel Curda was hanged for high treason in 1947.

Other Churches in Prague

|

|

On the top of the church face is a statue of St. Ignatius and one of the local attractions, namely the placement of the aureole surrounding the saint´s body. At that time, the aureole was perceived as considerlably seditious. Based on the clerical rules, only Jesus Christ was allowed to have an aureole around his whole body, however the position of the Jesuit order was so strong that this extravagance was tolerated.

The church painting decorations were carried out by Jan Jiri Heintsch and the sculptural decorations by Matej Vaclav Jackel whose works we know mainly in reference to the Charles Bridge. Another somewhat mystical attraction of the church is the notice on the tympanon completed by a chronogram.. In that inscription, selected numbers are indicated in capital letters which represent the year 1671 when the statue of St. Ignatius was placed onto the church roof. The text itself concerns the honour to St Ignatius.

|

The church is a brick-made three-aisle basilica with a transversal nave in the shape of the cross. The church front features two 120-foot towers with bells and a tall gable with portal above the main entrance with sculptures. The interior of the church has richly-colored stained-glass windows as well as paintings and sculptures by Czech national artists.

The square on which the church is located, Namesti Miru (English: "Peace Square") is is a pleasant area dominated by the church and other historic buildings. The plazad is a large, nicely-landscaped central area with many benches where locals like to sit and chat, read or watch their kids or dogs play. This is also where the Christmas market takes place in December and where occasional events and live band performances are held. For our part, we relaxed here for a while eating some gelato that we had purchased nearby.

Underneath the square is the same-named Prague Metro station built in the late 1970s. One entrance to the station is near the church, and others are at the other end of the square. The station was completed in 1978, as was originally the terminus of Line A, until it was extended in the 1980s. Namesti Miru is the deepest station on the Prague Metro and in the European Union. Its platform is situated 160 feet below the surface. As a consequence the station has the longest escalators in European Union- almost 300 feet long. If you simply stand on a moving step, it takes 2 minutes and 15 seconds to ascend or descend.

|

|

St. Martin's Church became the subject of scientific research after the discovery of its Romanesque base during the renovation of the early 20th century. In 1905 a comprehensive study of the base was published. The original plan appeared to be a pair of inner galleries in the southeast and northeast corners with access through two staircases in the thickness of the wall and a single steeple in the western part of the nave. Gothic modifications were made during the reign of Charles IV after 1350. The shrine was constructed in 1358 and various other modifications were made in the following years. In 1414, St. Martin's parish priest gave Communion in the church in the Protestant way, one of the first times in Bohemia. The church's current ground plan dates from a rebuilding completed in 1488.

A Baroque portal was built on the north side facing the street in 1779, and the arcades between the naves were plastered. In 1784, the church was "decommissioned" by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor; it became a two-storey building with shops on the ground floor and a residence above. In 1904 the church was bought by the City of Prague and a reconstruction effort begun. After the First World War, the church was assigned to the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, and it has functioned as a church since.

Miscellaneous Pictures from Our Walk

|

|

Certainly the shots Fred took of the architectural detail on many of the buildings we passed will give you an appreciation for the style prevalent throughout this very old city. And perhaps you will get a chuckle or two from some of the pictures I took.

At Jeffie's Apartment

|

Fortunately, Google has done that job for me; "street view" is available along Ruska, the street Jeffie is on. Her building is actually on the southeast corner of Ruska and Finska (Russia and Finland Streets, I suppose), and the Google view of it is at right.

There is a little pub on the ground floor corner, and the actual entry to the residential floors of the building is one door to the southeast along Ruska. Jeffie is on an upper floor, but fortunately, her building was retrofitted with an elevator a few years ago.

Most of the older buildings in the city were either built without elevators or before they became commonplace. But the desires of renters and buyers being what they are, many building owners have found it necessary to add elevators so they can get top dollar for their rentals.

Of course, adding an elevator inside a building is an expensive proposition; the only place to put one would logically be in an existing stairwell, and the stairs are needed for safety and so can't simply be removed. The solution was simple and straightforward.

|

But at left is an aerial view of a typical block in the residential area of Prague. Note that the buildings themselves are on the outside of the block, and together they enclose an open central area. Usually there is one access from the outside for vehicles, but access to the inner area is almost exclusively for the residents and occupants of the block's buildings. Jeffie's building, for example, has a little patio and garden area. On the aerial view, I have marked some of the many outside elevator shafts that have been added. In Prague, as in Barcelona, there is block after block similar to this one.

Most of these "grafted-on" elevator shafts have glass on the outside which makes the ride up very scenic. Usually there is a view of the inner courtyards of the buildings arranged around a block; sometimes there are little gardens, or parking areas, or something else in these interior spaces. It was reminiscent of Barcelona, except that the block here in Prague are far from regular in shape.

We took the elevator up to Jeffie's floor and she showed us the apartment. It was very nice inside, with plenty of room; the apartment was a real "find", especially as it was so close to the center of the city.

|

|

In addition to the living room, there was a separate bedroom and bath, as well as a small kitchen in the room that also served as the entry and where Jeffie has everything that her two cats need.

Although the apartment was spacious enough that one could spend a lot of time in it without feeling cramped, I get the impression that Jeffie doesn't do much "staying at home". She is either seeing clients on weekdays or traveling someplace new on weekends. We would be taking a couple of short trips out of Prague while we were here, and it would quickly become apparent how much there was to do within an hour's train ride from town. But Jeffie also keeps an eye out for special air and train fares to far-flung destinations, and she takes advantage of as many of them as she can. She's been to 33 countries so far, and I have no doubt that pretty soon she will exceed my own total of 44- all the more amazing when you consider that I've been traveling for a lifetime, while the vast majority of Jeffie's new countries have come in only a couple of years.

We really liked Jeffie's apartment, and hung out for a while before Jeffie walked with us to a nearby tram stop to help us find the right tram to take us back out west to our hotel.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

May 27, 2017: Karlstein Castle; Troja Palace; Prague Botanical Garden |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |