|

January 26, 1971: Climbing Mt. Fuji |

|

January 23-24, 1971: A Walking Tour of Tokyo |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |

Monday morning dawned bright and clear, for a change, and we hoped that was a good omen for our day trip to the Nikko Shrine and Lake Chuzenji.

NOTE from 1975:

As I write the narratives for my slide pictures, I am including some of the information from the book we'd bought- Japan on 10 Dollars a Day. I brought that book back with me from Korea so that I could use it to organize my memories of the traveling that I did in Japan- both on this trip and on my second trip later this year.

NOTE from 2021:

Now that I am creating online pages out of the scanned slides and the narrative that I wrote 45 years ago, I wanted to include more information from Japan on 10 Dollars a Day. Sadly, I lost track of the paperback book many years ago- either in my move from Indianapolis to Chicago or from Chicago to Dallas. All was not lost, though. A quick search on Amazon and I found a seller who had one used copy left, and so I ordered it. It is sitting here on my desk as I work on the pages for both Japan trips. Incidentally, the cover price of the book was $2.50 for the exact 1970-1971 edition that I had then; that same edition, which is the one I found on Amazon, was around $14, including shipping.

An Introduction to Our Nikko Day Trip (added in 2021)

|

| "The trip to Nikko has come to have some of the trappings of a pilgrimage, so far as visitors to Japan are concerned. To begin with, most of the Japanese themselves go there, first as bright, chattering school-children in large mobs conducted by guides, and then, in later life, as bright, chattering, camera-carrying adults in large mobs conducted by guides. It's safe to say that if you choose to go to Nikko alone (i.e., not with a conducted group), you'll be one of the minority. You'll also enjoy it more. All the information you can glean about it in advance is calculated to intimidate you. Thre is talk about dozens of elaborately-decorated temples and shrines, sacred bridges and winding highways, and cable car rides up to secluded lakeside villages up in the mountains. The implication you'll get is that you need to stay for several days just to get around and see everything. And as for getting from one point to the next- horrors! Better have an air-conditioned limousine with bilingual chauffeur in attendance. Nonsense! It's true that 90 percent of the Americans who go to Nikko do so laden with baggage, interpreters, phrase books and wads of thousand-yen notes in readiness to hire cars. But it' also true that you can go to Nikko with nothing more than supreme self-confidence and something to read on the train, take a series of buses and cable cars, visit all the major things of interest and return the same day, without ever having had to utter a word of anything other than English for the entire day. And once you've done that, you'll no longer feel helpless in a foreign country where you don't speak the language." |

Getting to Nikko

|

We expected all the seats to be full, but it turned out that by reserving seats, we got in a reserved car, which didn't have many people at all, so we had plenty of room for our camera gear and so many windows to take pictures from the we spent some time debating which were the cleanest. We got settled and started out right on time. You've seen the city, so the first shots I took were in the country.

I took a number of shots of typical farmhouses and small towns all along the way. I was a little surprised that most of the house roofs that we saw were made of tile, not the thatched roofs that are prevalent in Korea. There is still some snow on the ground, and the amount got larger as we moved North and up. Remember too, that if some of the pictures are blurry in the foreground, it is because the train is moving rapidly.

There is one interesting thing about Japanese residences. Almost all of them that have room or can afford it have a small garden in front, filled more with trees and shrubbery than flowers. Many of the wealthier residences also have an entrance gate, in Japanese Torii style. The homes look Japanese enough without them, but I think the trend toward home beautification is a good one, with pleasing results.

There was no way I could open the railway car window, or the pictures I took would have been much better. Still, I am impressed with how neat and clean everything is. This is quite a contrast from Korea, and actually quite a contrast from places in the States, too.

|

In the slideshow, you will see views of the farmland north of Tokyo, as well as some of the rural houses in this area. You will see some of the country homes that are also sprinkled among the farms, including a few that were quite large, and which it would be hard to distinguish from houses in the United States- particularly in suburban or rural areas.

As we approached the mountain resort areas, there was less and less agriculture, and the mountains become more and more prominent, of course- including our first view of Mt. Nantai, one of the highest in the area around Nikko. Just from the scenery, we were able to understand something of Japanese life in the country. As we ascended into the mountainous area it got colder and snow cover thickened.

When you click on the image at right to view the slideshow, you will be able to move through the pictures by clicking on the little arrows in the lower corners of each one, and you'll be able to track your progress using the index numbers in the upper left of each one.

In the Town of Nikko

|

In the aerial view at left, you can see where these sites are in relation to the town itself. In case you are curious, the aerial view spans about 20 miles east to west.

Nikkō is located in Tochigi Prefecture, and about one hundred thousand people live in the area. (By 2020, the population will have declined by about 20 percent to about 80,000. The reasons for this are numerous, but since tourism has remained fairly stable over the years, the combination of efficiencies in handling them and the aging of the Japanese population has led to this decline.

|

The recorded history of the area begins in 766 when Shōdō Shōnin established the temple of Rinnō-ji in 766, followed by the temple of Chūzen-ji in 784. The village of Nikkō developed around these temples. The shrine of Nikkō Tōshō-gū (the one we will see today) was completed in 1617 and became a major draw of visitors to the area during the Edo period. It is known as the burial place of the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu. A number of new roads were built during this time to provide easier access to Nikkō from surrounding regions.

Six years after my visit here, UNESCO will begin designating various sites around the globe as "UNESCO World Heritage Sites"- denoting natural and man-made features as part of the global history of mankind, making them eligible for various protective measures and funding. The list began with 12 original sites- such as Yellowstone National Park and the Cathedral at Aachen, Germany- but will expand over the years to over 1000 sites. The "Shrines and Temples of Nikko will be added to the list in 1999.

NOTE from 2021:

Interestingly, by the time I create the page you are now reading, I will have visited many of these sites in my travels- including five of the original twelve. These five will be Yellowstone National Park (US), Mesa Verde National Park (US), the Island of Goree (Dakar, Senegal), the City of Quito (Ecuador), and the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador).

|

|

During the Meiji period, Nikkō developed as a mountain resort, and became particularly popular among foreign visitors to Japan. The Japanese National Railways began service to Nikkō in 1890 with the Nikkō Line, followed by Tobu Railway in 1929 with its Nikkō Line.

This could easily be in our own West, maybe in Wyoming, or somewhere. There would be a lot of activity in a small town when the train from the big city arrived. The town definitely had a resort flavor. The stores seemed to be selling souvenirs and such; at least a lot of the items had pictures of the mountains and the name of the town on them. I would assume that this is a lot like a small resort town in the Rockies, for example.

|

|

When we arrived in the station, we followed the locals off the train and out to the front of the railway station. And it was right here where the Frommer book took over. Wilcock's narrative was uncannily accurate:

| "When you get off the train at Nikko Station, you'll find the street bustling with taxi drivers wanting to take you for a ride. Ignore them. The bus on the left, already thronged by eager Japanese, is bound for the picturesque village of Chuzenji in the mountains. You're going thre, too, eventually; bu tno tyet. At the ticket window, get a ticket for "Toshogu Shrine"; it costs 20Y. Then board the Chuzenji bus." |

|

The book was pretty amazing. After a while, I thought I would not be surprised if we read something like: "Politely decline the offer by the taxi driver in the red shirt to take you to the shrine, but turn to the left and walk to the ticket window where the six people are waiting in line." It was as if the book had been written only hours before, sometimes. One thing I remember is that Wilcock said that the taxi drivers would be offering to take us to Lake Chuzenji for 1000Y, but when one came up to us, the offer was for 1100Y. I never figured out whether we looked like easy marks or whether the difference was the result of inflation.

But Wilcock's advice was to take the bus. We used a little map in the at the ticket window to point to where we wanted to go, and bought a ticket. When we got on the bus, we pointed to the Nikko Shrine on the map, and the bus hostess told us where to get off. Nobody spoke one word of English, except for "yes," "no," and "thank you." It was really quite amazing. After a few minutes, the bus headed off.

|

|

|

Together with Futarasan Shrine and Rinnō-ji, Nikkō Tōshō-gū forms the Shrines and Temples of Nikkō which, as I said earlier, will be made into a UNESCO World Heritage Site about thirty years from now. As of my visit today, though, this designation does not exist. Even so, the 30+ structures at Nikkō Tōshō-gū and the ten more at the other two shrines, are obviously an important and revered site in Japan- national treasures in any sense of the word.

Of course, the guidebook told us this, and I am sure the placards and informational signs that were placed at most of the major buildings and other structures said the same thing, although they were all in Japanese. But to me, what really expressed the reverence and respect given to this site was how the many Japanese tourists behaved. Tokyo is hustling and bustling, and even though people take great care not to bump into you (except, perhaps, on the subway, which seems to have an etiquette of its own), they move about rapidly and with a sense of purpose. But that attitude was missing here. All the Japanese tourists we saw, whether in groups or singly, moved much more slowly- seemingly with a desire to simply "take it all in" and experience the feelings and emotions of the site's various builders. I also got the impression that these tourists were very familiar with the personages who built the various structures or who were honored by them. It was an interesting feeling, my interpretation of the attitude of the Japanese visitors, and as it turned out Nikko would be far from the only time I would experience it.

Our Entry to Nikkō Tōshō-gū

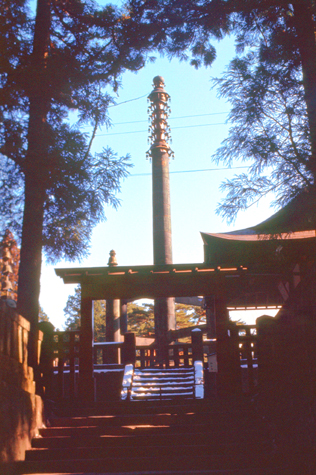

The Sorin-to |

(Picture at left) This is the 44-foot bronze Sorin-to that was built in 1643 "to repel evil influencs" looks like a moon rocket on the pad ready for takeoff.

(Picture at right)

|

The Five-Storey Pagoda |

Tōshō-gū is dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was initially built in 1617, during the Edo period, while Ieyasu's son Hidetada was shōgun. It was enlarged during the time of the third shōgun, Iemitsu. Ieyasu is enshrined there, where his remains are also entombed. This shrine was built by Tokugawa retainer Tōdō Takatora. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate carried out stately processions from Edo to the Nikkō Tōshō-gū along the Nikkō Kaidō. The shrine's annual spring and autumn festivals reenact these occasions, and are known as "processions of a thousand warriors".

|

About 1630, the story goes, one such lord, Masatsuna Matsudaira, had been appointed to be one of the commissioners whose responsibility it would be to get the work done.

|

He planted avenues of cedar trees at all approaches to the shrine- a total of 15,000 cedars stretching 25 miles if put in a single file spaced as they are on the grounds. You can see one such avenue at left, and a couple of these trees alongside one of the shrines pathways in the picture at right.

Most of these trees, some now hundreds of feet high, are still standing, still thriving, and still growing. Certainly the astute lord found the "gift that keeps on giving"!

There are many interesting structures here on the grounds of the shrine, and we will take a look at many of them in a moment. But there was one particular structure that Wilcock went on and on about in the guidebook, so we just had to make it one of our first stops. It was easy to find, not only because of the guidebook's excellent directions but also because it seemed as if every other tourist wanted to see it as well.

|

Below are extracts from the picture at right, blown up so you can see more detail. I apologize for the quality of the enlargements, but considering that the original picture was a slide, and that it was scanned a quarter-century after it was taken, and then small segments were digitally enlarged by a factor of 10, the result really isn't half bad.

|

|

|

(4) the higher one seeks, the more he wants. Know when to stop wanting beyond his needs.

|

(6) A mate helps one to enjoy life, but he must remember that life is not always honey.

|

(8) Expecting monkey- arrival of a new generation shows god's love, paternal love and child's compassion.

Incidentally, the maxims are one of the quaint English translations that we found in the 100Y guidebook to the shrine that we purchased and carried around with us. As I write these slide narratives in Chicago in the late 1970s, I am able to copy this information into my narrative.

Exploring Nikkō Tōshō-gū

I think that perhaps the easiest way for you to wander through Nikkō Tōshō-gū with us and see what we saw is via a series of slides (pictures) that you can go through at your own pace. I could just give you a long series of thumbnails to click on, but beyond five or six pictures this method becomes a bit tedious.

|

There are quite a few pictures available, and so I have also put little index numbers on each slide so that you can tell where you are in the sequence of images. At least you will know, eventually, that "this is where I came in". I hope you enjoy these images of Nikkō Tōshō-gū, but I definitely want to tell you that even fifty years later I am well aware that the pictures I took hardly even a passable job of showing you what it was really like to wander around this World Heritage Site. If you ever get a chance to visit in person, jump at it. You will be glad that you did.

I also want to add some comments that really pertain to many of the buildings and features and to the shrine site itself. One is that the buildings are built of beams that expand and contract according to dampness, keeping conditions inside relatively constant. Inside the various buildings are many contributions including a candlestick candlestick which was presented by a king of Holland. It was, in fact, made by Dutch people in Nagasaki. The reason why there are contributions from the Dutch and the Koreans is that Japan had been closed for the world, and China, Korea and Holland were the only countries allowed to trade with them.

The entire wall in front of the Yomeimon Gate, and well as the gate itself, and other walls around the shrine area are done in a style of intricate carving, and there are many golden bells hanging from the eaves, painted dragons guarding them, and many other animals- real and fantastical.

Lake Chuzenji

|

If you look carefully at the aerial view above (circa 2020, of course), you will see that my marked route is not actually drawn on top of the road itself; the road was much, much more winding than my yellow route line might indicate. You can see the actual road on the aerial view.

|

|

As we ascended the steep, curving mountain road to go over the crest of the mountains to Lake Chuzenji, there was certainly a great deal of scenery to look at out the windows of the bus. At one point, we saw this bridge and also an old tramway that was closed in 1970.

|

|

The most prominent feature in the landscape in this area of Japan, and one that we could actually see from the train coming up from Tokyo, is Mt. Nantai.

|

The mountain is popular with hikers, and the trail to the summit starts through a gate at the Futarasan Shrine, located just west of the actual town of Chuzenji. Hiking to the top is only allowed from May through October.

Mount Nantai is/was actually a volcano, but has long been thought to be extinct. I might note that in 2008, the Japan Meteorological Agency was asked to reclassify Mount Nantai as "active" based upon work done by scientists who uncovered evidence of an eruption approximately 7000 years ago. In the historical period, Mt. Nantai has been the nearby mountain peak supplying water to the various Shinto shrines in the area. Because of this, Mt. Nantai is considered a sacred mountain.

I have never driven on twisty, switch-backed mountain roads. Yes, I bought a car after college, but drove it only to Fort Harrison and then to Fort Lee. I may have driven it up to Asheville at some point, but the roads in Western North Carolina are quite good. Riding in this bus, with a number of nonchalant Japanese and a few other tourists, was quite a different experience.

|

We were riding in a full-length bus, and at each of the curves we were not sure that the bus would stay on the road. It did, but just barely, leading us to believe that the road was specifically designed to accommodate the bus, but nothing larger or longer. Whenever the bus came to a turn, the driver would calculate it almost exactly, turning the bus in as wide a radius as possible to keep from hitting the guard rail. Those of us in the back of the bus could only watch helplessly as the guard rail whizzed past our window, the only thing between us and quite a drop. Dan and I were a little nervous, but the Japanese on the bus, most of them young and obviously on their way to go skiing, were nonchalant.

Click on the image at right to see these pictures. You can go from one to the next by clicking on the little arrows in the lower corners of each picture, and you can refer to the index numbers in the upper left to see where you are in the show.

The ninth picture in the slide show is another view of Mt. Nantai. It is 8197 feet high, and is sometimes called "Kurokami-yama" (black-hair mountain) or "Futa-ara-san" (two-storms mountain). There is a Shinto shrine at the foot of it, and the spirit of the mountain is enshrined in it.

After a three-quarters-of-an-hour bus ride (which, as I mentioned above, was quite exciting in places and would have qualified as an e-ticket ride at Disneyland), we arrived in the town of Chuzenji, and we got off just where the guidebook told us to.

|

On the aerial view at left, you can see this corner of the lake and how the town is laid out here. The bus dropped us off right in the center of town, within walking distance of just about everything.

The name "Chuzenji" comes from a 1000-year-old Buddhist temple which is still something of a mecca to the busloads of Japanese who come here.

|

|

Our guidebook told us that in winter one of the few things to do in the area (other than some small amount of skiing and other winter activities) was to take the "rope cableway" (most of us would call this an "aerial tramway") up to an observation point called Akechidaira.

As was usually the case, our little guidebook gave us explicit instructions for what to do in Lake Chuzenji, and we settled on two things, which I will get to in a moment. I just wanted to say that for almost our entire visit here in Japan, all we needed to do to get around and make ourselves understood was point, speak a few Japanese place names, say some common words like "ticket", and point to maps in our guidebook. Every once in a while, we were pleasantly surprised when some thirty-something Japanese, educated since the war, had learned quite a bit of English. Sometimes it was the person we were talking to, but other times some other Japanese person, perhaps just standing nearby, overheard us can came over to help translate. These people were never intrusive, but seemed genuinely helpful.

I was a bit surprised by this, since it had only been 25 years or so since the war, which had ended so horrifically for so many here in Japan. I did not come to understand the Japanese viewpoint until my second visit to Japan some half a year from now when I was returning to the United States after my Korean tour was over. But that is a story for an upcoming album page.

There were two things that we decided to do here. One was to make a visit to Kegon Falls, which are actually quite near to the town itself. The guidebook said there was a little tramway we could take for 100 yen or so that would take us up above the town to an observation platform. From here, you can get excellent views of the lake and the town. This is also the access point for viewing the falls themselves, and the building here houses an elevator that you can take to the bottom of the falls.

|

I've put an aerial view (circa 2020 of course) at the left. You can see the town of Chuzenji and where the observation platform is in relation to it. I tried to mark the general route of the two cable car routes, but I think that Google may have marked the falls as being too close to the town. But this is close enough, I guess.

I might mention two things. First, there was a little tramway that took us up to the falls access point and the observation platform that provided great views of the town and the lake. And there was a separate cable car up to the Akechidaira Observation Point. I probably didn't mark these correctly, as we were there fifty years before the aerial view was probably taken. (For all I know, the area has completely changed since we visited.).

Second, from my pictures and from my memory, I think the aerial view puts Kegon Falls a bit too close to the town, but, again, that hardly matters here. In any event, you can see the course of the Daiya River coming into Lake Chuzenji, and I suppose it really doesn't matter much exactly where along that course the falls were/are actually located.

Kegon Falls

|

|

We wanted to make sure that we didn't miss seeing the falls and getting down to the bottom, so we did that first, figuring we could always take our pictures of the lake and the town when we came back up.

|

|

In the autumn, the traffic on the road from Nikko to Chūzenji can sometimes slow to a crawl as visitors come to see the fall colors.

In 1927, the Kegon Falls was recognized as one of the "Eight Views" which best showed Japan and its culture in the Shōwa period. It is also listed as one of the "Japan’s Top 100 Waterfalls", in a listing published by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment in 1990. On the downside, the Kegon Falls are infamous for suicides, especially among Japanese youth.

Of course we took a number of pictures of the falls- some from the top observation platform, and some from the bottom of the falls (where we found the elevator letting us out onto an observation patio.

|

|

Looking at the falls straight on, it almost seems as if the water comes right out of the rock, as you can't see the river above the Falls very well. Actually, there really isn't a good vantage point for the falls from the top- unless you want to climb down from the upper platform and make your way through the woods and around to the top of the falls.

Ice Sculptures at Kegon Falls |

(Picture at left) About halfway down the length of the Falls, the rock walls are so close together that layers of ice have a chance to form, and the layers form a ring around the falling water, building up until the Falls are almost choked off. The blue tint to the ice was quite real.

(Picture at right)

|

Kegon Falls |

And two final pictures of the falls:

|

|

Before we head back up to the top of the falls, I want to include one more picture here, although I suppose this picture could have been taken almost anywhere in the world where there is mountainous terrain.

|

My guess is that the bottom of the falls was a couple hundred feet below the upper platform, and of course we had taken the elevator down. This shot was taken from that lower platform.

Kegon Falls itself is about 300 feet high; the lower platform was not quite at the bottom. The falls are fairly narrow- only about 25 feet wide. There are twelve small waterfalls in the middle part of the cliff. In the Wintertime, the book says, the falls will freeze.

The rock over which the falls cascade is part metamorphic, with lots of quartz, and part igneous, due to the volcanoes that used to be active in this area.

Looking back up from the observation platform, the way the rocks have been broken off is quite interesting, and presents a good example of perspective. It almost appears as if the whole mountain is a giant crystal.

Sadly, Kegon Falls are noted for the number of people that come here to commit suicide. A young student of the First High School in Tokyo named Misao Fujimura was the first- he jumped from the top of the falls on May 27, 1893. Since then, more than 100 people come here every year intending to jump, although I have no idea how many actually do jump or what measures are in place to prevent them from doing so.

|

The small resort town of Chuzenji is nestled along the lakeside just below Kegon Falls. The town is still pretty much closed up for the winter; its "season" is from mid-April to the end of November. During the summer the hotels are always full, and the lake itself is dotted with numerous pleasure boats. We took a few pictures of the area from here, and there are clickable thumbnails for these pictures below: (the fourth one is Chuzenji's largest hotel)

|

Earlier, we had thought that we might hire a taxi driver to take us around Lake Chuzenji; it seemed as if they were very reasonable, and we thought a few bucks should do it. When we'd inquired in town, though, we found that this would not be possible, as we did not have time to wait for the road to be built all the way around. So it was up to Akechidara.

Akechidaira Viewpoint

|

My pictures from the ride up and down were not particularly good, but I am going to include them here anyway. For a couple of them, I leaned out one of the open windows so I could look directly down.

|

|

During both my trips to Japan, I was going to be introduced to a lot of transportation options that I'd never experienced before, and this aerial tramway was one of them. (By 2021, as this page is being created, these would all be old hat, but on this trip they were all new to me.)

So, we got to the top of the aerial tramway and found ourselves inside the building housing the tramway station. We just walked outside to the observation platform, which was actually a multi-level affair that also allowed you to walk out onto the top of the mountain if you wanted. There was a lot of snow on the ground, so tramping through it with our street shoes wasn't a good idea.

We were first struck by the pretty amazing views looking to the west at Lake Chuzenji. We took a number of pictures looking in this direction, but few of them showed as much of the lake as I wanted to make a really good panoramic view. Fortunately, as I create this page today, I have some software that can merge photos together, and it turns out that three of the pictures I took fit together nicely, and that is the panoramic view that you can see below.

|

Here are four more pictures of the lake, the base of Mt. Nantai, and the town of Chuzenji:

|

|

|

I took another picture using that foreground tree, but I didn't like it as much:

|

It was really neat up here at the Akechidaira viewpoint, as there were marvelous views in all directions.

|

Anyway, there are about a dozen pictures to include here, and I've created a little slideshow to make it easy for you to look at them. If you will click on the image at left, I'll open up the slideshow in a new window. You can go forward and backward through the pictures just by clicking on the little arrows in the lower corners of each image, and you can use the index numbers in the upper left to track your progress. Enjoy looking at the views from Akechidaira!

We stayed at Akechidaira as long as we could, only descending when the day's next-to-last run was commencing. We got down to the bottom, and were just in time to buy a ticket on the Nikko-bound bus. Bidding fond farewell to Chuzenji, the bus started off to Nikko, absolutely full, mostly with kids and skis. We took a different route down the mountain, and road was, if anything, more winding that the one coming up. The bus ride to Nikko from Chuzenji costs 150 Yen, takes about 50 minutes, and is one of the most memorable one could have. There are many hairpin curves along the way, along a road that doubles back and forth like a coiled spring. At every curve, you are quite sure the driver isn't going to make it, but he does- only barely. The road is called Irohazaka Driveway, and would be a roaring success at Disneyland where people don't mind paying to be frightened half to death. In Nikko, we caught the train as darkness fell, and had a relaxing ride back to Tokyo and dinner.

|

January 26, 1971: Climbing Mt. Fuji |

|

January 23-24, 1971: A Walking Tour of Tokyo |

|

Return to the Index for the Japan Trip |