|

July 12, 1992: Taos and Rio Grande Gorge |

|

Return to the Index for the Santa Fe Trip |

On our last day in Santa Fe, we checked out of the El Farolito early, and then went by a couple of the shops we had visited and I got a gift for Larry- a Nambe platter. Then we headed out for Bandolier National Monument.

Getting to Bandelier National Monument

|

At Los Alamos, we turned south on New Mexico Highway 4 through White City. A few miles beyond that, we came to the Park Road on our left (south) and the entrance station for Bandelier.

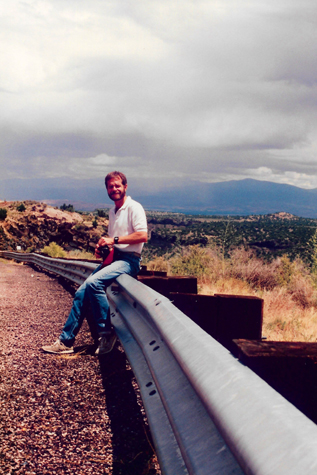

We took a few pictures along our drive to Bandelier; as with our drive yesterday, the scenery was pretty constantly beautiful.

|

Prior to the arrival of the narrow gauge Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad in 1880, the hamlet on the west side of the Rio Grande had been populated by ranchers and farmers for a hundred years as La Vega de los Vigiles. With the coming of the railroad the name of the hamlet was changed to Espaņola. The Chili Line of the RGWR was built along the Rio Grande, and extended into what is today downtown Espaņola. When the railroad began selling lots in the area, Anglo merchants, mountain men, and settlers slowly filtered into town. Frank and George Bond, Canadian emigrants, later created a business empire that dramatically influenced the importance of Espanola.

That importance began to wane because both passenger and freight traffic on the railroad declined; this forced the railroad to close in the early 1940s. Many locals followed the railroad to Santa Fe, Albuquerque and central Colorado; Espaņola's population fell dramatically. Most of the locals who remained would turn to farming as a way of life. Many people saw Espaņola as another failed railroad town, and the city removed the railroad tracks and the train depot in the 1960s, and the railroads completely vanished.

But we left Espanola behind when we turned west towards Los Alamos. We went right past Los Alamos without stopping, but it looked like an interesting town, and of course its importance in American history was out of proportion to its size. Since we didn't stop, I won't say much about the city, its history, or its importance. We turned south on Highway 4 towards Bandelier.

|

(Picture at left) This picture was taken along Highway 4. I have not taken many trips out West; the first one that I can remember was the trip with Fred to Guadalupe just a month ago. So the difference in terrain still impresses me. Here, as the road passed through a cut in the rock, the sandy formations made it look as if it had been snowing.

(Picture at right)

|

|

We found the entrance road for Bandelier National Monument on our left, paid our entrance fee, and headed down the Park Road to Frijoles Canyon.

Bandelier National Monument

|

Bandelier was designated by President Woodrow Wilson as a National Monument on February 11, 1916, and named for Adolph Bandelier, a Swiss-American anthropologist who researched the cultures of the area and supported preservation of the sites. The National Park Service co-operates with surrounding pueblos, other federal agencies, and state agencies to manage the park. The monument has around a hundred thousand visitors each year.

In October 1976, roughly seventy percent of the monument was included within the National Wilderness Preservation System, and the Valles Caldera National Preserve (which will be our next destination today) adjoins the monument on the north and west, extending into the Jemez Mountains.

Much of this area was covered with volcanic ash (the Bandelier tuff) from an eruption of the Valles Caldera volcano 1.14 million years ago. The tuff overlays shales and sandstones deposited during the Permian Period and limestone of Pennsylvanian age. The volcanic outflow varied in hardness; the Ancestral Pueblo People broke up the firmer materials to use as bricks, while they carved out dwellings from the softer material.

|

Humans have lived in this area for at least 10,000 years, although permanent settlements date to only 1150AD. By 1550, these people had moved closer to the Rio Grande by 1550. The distribution of basalt and obsidian artifacts from the area, along with other traded goods, rock markings, and construction techniques, indicate that its inhabitants were part of a regional trade network that included what is now Mexico. Spanish colonial settlers arrived in the 1700s, and a local pueblo brought Adolph Bandelier to visit the area in 1880. Looking over the cliff dwellings, Bandelier said, "It is the grandest thing I ever saw."

Based on documentation and research by Bandelier, there was support for preserving the area and President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation creating the monument in 1916. Supporting infrastructure, including a lodge, was built during the 1920s and 1930s. The structures at the monument built during the Great Depression by the Civilian Conservation Corps constitute the largest assembly of CCC-built structures in a National Park area. The group of 31 buildings illustrates the guiding principles of National Park Service- rustic architecture based on local materials and styles. In recognition, Bandelier has also been designated as a National Landmark District.

During World War II the monument area was closed to the public for several years, not because tourist visitation dropped off sharply, but because the lodge and the other buildings were being used to house personnel working on the Manhattan Project at nearby Los Alamos to develop the atomic bomb. We continued down the Park Road, descending for about two miles until we came to the parking area for the Visitor Center and the various trailheads. There are numerous backcountry trails here, but our purpose today is to have a look at the Puebloan ruins.

An Overview of the Main Loop Trail

|

To try to show you what the trail was like, I have grabbed an aerial view of the south end of the Frijoles Valley and marked the trails and major features on it. (The actual valley runs from northwest to southeast, but I have rotated the aerial view so that it fits better here on the album page.

You can scroll all the way to the right to find the Visitor Center and the beginning of the trail, and you can return here as you wish to follow us along on our four mile walk this morning.

The Big Kiva

|

The next stop on the trail was the Big Kiva.

|

A kiva is a room used by Puebloans for religious rituals, many of them associated with the kachina belief system. The Big Kiva here in Bandelier once had a roof covering it; many kivas were actually either underground or below grade with roofs. Similar subterranean rooms are found among ruins in the American southwest, indicating uses by the ancient peoples of the region including the Ancestral Puebloans, the Mogollon and the Hohokam. Those used by the ancient Pueblos of the Pueblo I Era and following, designated by the Pecos Classification system developed by archaeologists, were usually round and evolved from simpler pithouses.

Tyuonyi

|

These sites date from the Pueblo III Era (1150 to 1350) to the Pueblo IV Era (1350 to 1600)- dates confirmed by tree-ring dating, a method widely and successfully used by archeologists in the Southwest. Ceiling-beam fragments recovered from various rooms have been dated between 1383 and 1466. This general period seems to have been a time of much building in Frijoles Canyon; a score of tree-ring dates from the Rainbow House ruin, which is down the canyon a half-mile, also fall in the early and middle 15th century. Perhaps the last construction anywhere in Frijoles Canyon occurred close to 1500, with a peak of population reached near that time or shortly thereafter.

The century before Tyuonyi's construction is thought to have been characterized by intense change and migration in the Ancestral Puebloan culture. The period of highest population density in Frijoles Canyon corresponds to a period contemporaneous with a wide-scale migration of Ancestral Puebloans away from the Four Corners area, which was suffering a deep drought, environmental stress, and social unrest in the Pueblo III period. Scholars believe that some Ancestral Puebloan groups relocated into the Rio Grande valley, southeast of their former territories, founding Tyuonyi and nearby sites. The pueblo was abandoned by 1600. The inhabitants relocated to pueblos near the Rio Grande, such as Cochiti and San Ildefonso, which are still occupied.

|

(Picture at left) Here are Fred, myself and Greg at the Tyuonyi ruins in Bandolier. As usual, Fred brought his tripod so that we could take group pictures.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Shortly after walking through Tyuonyi, the trail split off to the right and headed uphill. Our trail guide said to take this split to continue following the interpretive markers which lead up to the distinctive cave dwellings located within the canyon wall, and that we would encounter stairs and railings to help navigate our way up to the cave dwelling area. After ascending a bit, I got better views of Tyuonyi.

Myself and Greg with the Tyuonyi ruins behind and below us. |

|

The trail went up some stairs and a ladder, as advertised, and we found ourselves at the base of the cliffs about a hundred feet or so above the valley floor.

|

The valley is not quite so fertile as it looks from up above, although there is water running through it. Here you see the typical high desert vegetation, although right down by the water the vegetation is much different.

The Cliff Dwellings

|

|

Here along the trail at the base of the cliffs you can see the ruins of some of the rooms that were built at these spots. The entire area has a great many of these cliff ruins; the guidebook said that at one time some thousands of people may have lived here in this valley and in the cliffs around it. This picture provides a good contrast between the dwellings that nature provided in the cliffs and the ones that had to be built from scratch on the valley floor.

Tyuonyi Seen from a Cavate |

(Picture at left) The self-guiding trail takes you up along the cliff face to see the actual cliff dwellings, and from there you can get a good perspective of the ruins on the valley floor. This shot was taken from inside one of the rooms that had been dug out of the cliff and looks back down to the valley floor. You can see the circular nature of the ruins clearly from here.

(Picture at right)

|

Greg and Fred at the Cliff Face |

Fred in a Natural Cliff Face Opening |

(Picture at left) This particular hollow is not really one of the rooms that had been intentionally constructed by the valley inhabitants; it looked more like a natural opening. It is in a natural cut in the cliff, in a shady area just off to one side of the trail.

(Picture at right)

|

Myself and Fred in Cavates |

It looks as if the cliff face has been punched full of holes, and that is not far off the mark. The cliff face is made of a material called "tuff," which is a porous, sandy material that you can dig out with your hands. Once you get a hole dug, then it will remain stable unless you intentionally dig at it further.

The Cliff Face at Bandelier NM |

(Picture at left) You can see the guide rail for the trail at the right of the picture. We are looking up at some of the actual dwellings in the cliff face. Not all of them were accessible by the public; I suppose that some of them are more fragile and must be protected.

(Picture at right)

|

Fred at the Bandelier Cliff Dwellings |

I imagine the cliff dwellers dug out spaces for their dwellings, and then simply stopped; just walking on the tuff surface is not enough to compress and dislodge it. I would imagine that Frijoles Canyon would be easy to defend, as there are only a limited number of entrances to it. The trail eventually came to an end, and turned back down into the valley below. Before we descended down to the valley floor, I got a really good picture of Fred at the cliff face. This excellent picture looks northwest up the canyon. Here at the end of the trail, many of the openings were roped off, but we had ample opportunity to get in some of them earlier on. By this time of the day, the weather was very, very warm, and I for one was looking forward to getting back down into the trees along the river.

|

(Picture at left) Here is a view of the cliff dwellings seen from the trail back under the tree canopy on the valley floor. The trail through the trees provided a welcome respite from the sun. It is unusual to see tall trees like these in this part of New Mexico; there has to be sufficient water and a sheltered place for them to grow, conditions that are met here in Bandelier.

(Picture at right)

|

|

When we got down here into the trees, we came to a trail intersection. We could either turn right to have a look at Alcove House, or we could return to the Visitor Center.

Alcove House

|

Formerly known as Ceremonial Cave, this dwelling is located 140 feet above the floor of Frijoles Canyon. Once home to approximately 25 Ancestral Pueblo people, the elevated site is now reached by 4 wooden ladders and a number of stone stairs. In Alcove House, there is a reconstructed kiva and the viga holes and niches of former homes. Imagine climbing these ladders, carrying whatever supplies were needed, to this lofty home. If you look closely at the picture at left, you'll see a red-shirted person on one of the ladders; this should give the picture some scale.

Walking through the forest, we heard a good many animal sounds- not unusual since wildlife here is locally abundant. Deer and Abert's squirrels are frequently encountered in Frijoles Canyon. Black bear and mountain lions inhabit the monument and may be encountered by the backcountry hiker. A substantial herd of elk are present during the winter months, when snowpack forces them down from their summer range in the Jemez Mountains.

Notable among the smaller mammals of the monument are large numbers of bats that seasonally inhabit shelter caves in the canyon walls, sometimes including those of Frijoles Canyon near the loop trail. Wild turkeys, vultures, ravens, several species of birds of prey, and a number of hummingbird species are common. Rattlesnakes, tarantulas, and "horned toads" (a species of lizard) are occasionally seen along the trails.

Eventually, the trail climbed back out into the sunlight and up to the base of Alcove House. We found that to get into Alcove House, one has to climb three sections of very steep ladders, and at this point Greg bowed out. He didn't think he would be able to climb up the ladder because, as it turns out, he has something of a fear of heights. I thought Fred did, too, but the actual height was not enough to make him nervous. Even so, we both spent time focusing on the ladders in front of us.

|

(Picture at left)

(Picture at right)

|

Right-Hand Title |

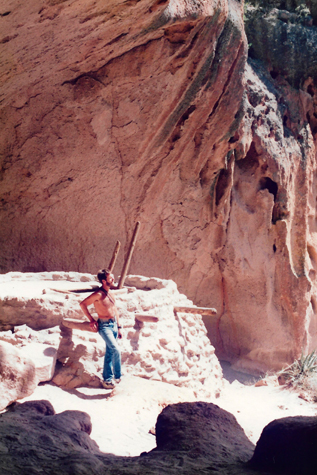

It has gotten so warm that I finally took my shirt off; it was particularly warm up here in the bright sunlight climbing up and down in Alcove House. Looking at the pictures, I can see now that I should have joined a gym then.

|

|

The whole area looks as if it was hollowed out by the inhabitants, although there might have been a natural shelf here to start with. I wondered about that, because the rock here seemed much tougher than the easily-worked tuff that we saw earlier.

We didn't want to stay up here too long, because we knew Greg was waiting for us, so we took just a couple more pictures before heading back down.

|

(Picture at left) Fred called for me to stand still outside the main kiva at Alcove House so he could get a picture. You can see that this particular kiva was built partially by digging down into the cliff itself and then, when the digging became presumably very difficult, the kiva was built up to the required height. You can see the beams that supported the ceiling, although I suspect they are not the original ones.

(Picture at right)

|

|

We got back down to the bottom of the first ladder, and saw that Greg had moved a ways down the trail so he could be in the shade of the trees. We rejoined him, and before starting back to the Visitor Center, took our last two pictures in Bandelier:

|

(Picture at left) Here are Fred, myself, and Greg alongside the stream running through the Frijoles Canyon. We have left Alcove House and are getting ready for the leisurely walk back to the Visitor Center. We would be following this stream most of the way. The whole setting was very beautiful, so Fred set up his tripod to get this shot.

(Picture at right)

|

|

We had some lunch at the little cafe at the Visitor Center, and then we drove back out of Bandelier NM to head off for our drive through the Jemez Mountains.

Valle Grande and the Jemez Mountains

|

|

The first stop (not counting one pullout at a scenic forest stream where Fred took a picture of some local flora) that we made was at a huge valley that we saw off to our right as we were driving along. We could see that there was a turnout and some sort of marker so we pulled off to have a look.

|

Here are Greg, me and Fred at Valle Grande; this shot lets you see much of the huge valley. Along the tree line to the right and in the far distance to the left we could make out houses or buildings. I would estimate five miles or more to the mountains in the distance.

The caldera is, of course, very old, predating human occupation of North America by more than a million years. Actual use of Valles Caldera dates back to the prehistoric times: spear points dating to 11,000 years ago have been discovered. Several Native American tribes frequented the caldera, often seasonally for hunting and for obsidian, used for spear and arrow points. Obsidian from the caldera was traded by tribes across much of the Southwest.

Eventually, Spanish and later Mexican settlers as well as the Navajo and other tribes came to the caldera seasonally for grazing with periodic clashes and raids. Later, as the United States acquired New Mexico as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the caldera became the backdrop for the Indian wars with the U.S. Army. Around the same time, the commercial use of the caldera for ranching, and its forests for logging began.

|

The caldera became part of the Baca Ranch in 1876. The Bacas were a wealthy family given the land as compensation for the termination of a grant given to their family near Las Vegas, in northeastern New Mexico. The family was given several other parcels by the US Government as well, including one in Arizona. This area, 100,000 acres, was called Baca Location number one. Since then, the land has been through a string of exchanges between private owners and business enterprises. Most notably, it was owned by Frank Bond in the 1930s. Mr. Bond, a businessman based in nearby Espaņola, ran up to 30,000 sheep in the calderas, significantly overgrazing the land and causing damage from which the watersheds of the property are still recovering.

The land was purchased by the Dunigan family from Abilene, Texas in 1963. Pat Dunigan did not obtain the timber rights, however, and the New Mexico Lumber Company logged the property very heavily, leaving the land scarred with roads and removing significant amounts of old-growth douglas fir and ponderosa pine. Mr. Dunigan bought out the timber rights in the 1970s and slowed the logging. He negotiated unsuccessfully with the National Park Service and the US Forest Service for possible sale of the property to one entity or the other in the 1980s.

(I might note that the sale was finally made and The Valles Caldera Preservation Act of 2000 signed by President Clinton created the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The Dunigan family sold the entire surface estate of 95,000 acres and seven-eighths of the geothermal mineral estate to the federal government for $101 million. As some sites of the Baca Ranch are sacred and of cultural significance to the Native Americans, 5,000 acres of the purchase were obtained by the Santa Clara Pueblo, which borders the property to the northeast. On the southwest corner, 300 acres would become part of Bandelier National Monument.)

|

Valles Caldera is one of the smaller volcanoes in the supervolcano class. The circular topographic rim of the caldera measures 13.7 miles in diameter. The caldera and surrounding volcanic structures are one of the most thoroughly studied caldera complexes in the United States. Research studies have concerned the fundamental processes of magmatism, hydrothermal systems, and ore deposition. Nearly 40 deep cores have been examined, resulting in extensive subsurface data.

Valles Caldera is the younger of two calderas known at this location, having collapsed over and buried the older Toledo Caldera, which in turn may have collapsed over yet older calderas. The associated Cerros del Rio volcanic field, which forms the eastern Pajarito Plateau and the Caja del Rio, is older than the Toledo Caldera. These two large calderas formed during eruptions 1.47 million and 1.15 million years ago.

The caldera and surrounding area continue to be shaped by ongoing volcanic activity. The El Cajete Pumice, Battleship Rock Ignimbrite, Banco Bonito Rhyolite, and the VC-1 Rhyolite were emplaced during the youngest eruption of Valles Caldera, about 50,00060,000 years ago. Seismic investigations show that a low-velocity zone lies beneath the caldera, and an active geothermal system with hot springs and fumaroles exists today.

|

The lower Bandelier tuff which can be seen along canyon walls west of Valles Caldera, including San Diego Canyon, is related to the eruption and collapse of Toledo Caldera. The upper Bandelier tuff is believed to have been deposited during eruption and collapse of Valles Caldera. The now eroded and exposed orange-tan, light-colored Bandelier tuff from these events creates the stunning mesas of the Pajarito Plateau.

These calderas and associated volcanic structures lie within the Jemez Volcanic Field. This volcanic field lies above the intersection of the Rio Grande Rift, which runs north-south through New Mexico, and the Jemez Lineament, which extends from southeastern Arizona northeast to western Oklahoma. The volcanic activity here is related to the tectonic movements of this intersection.

We got back in our car and continued west on Highway 4. It passed a number of trailheads where we could see cars parked, and the trails looked really neat. Fred and I made a mental note that we might put the Jemez Mountains on our list of relatively nearby places that we might go to for long weekends to do some hiking.

|

Here at Soda Dam, we learned about more spots in Jemez Mountains that might be worth a return trip. One of them, was Jemez Springs, the trailhead for which we passed just before Soda Dam. Situated in the Jemez Mountains, Jemez Springs, and the small town of the same name, are located entirely within the Santa Fe National Forest. The village is sited on the Jemez River in the red rock San Diego Canyon. State Highway 4 passes through the settlement on the east bank of the Rio Grande tributary. Geothermal springs in and near the village feed the Jemez River.

The Jemez River paralleled Highway 4 for about six miles, until we got down into the more settled areas where the pueblo towns were. All along the way, it was extremely picturesque.

|

(Picture at left) Water flowing through Soda Dam. Not all of this water comes from the carbonic springs; some of it is from a small creek that flows into the dammed-up portion just above this site, at which point it is joined by the warm spring water.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Highway 4 continued south towards Jemez Pueblo, and just before we got there, Fred got a nice picture of the very scenic Jemez Mountains. As the highway came down out of the mountains, it passed through many small pueblos, which are now just like small towns. The whole area is very scenic, but isolated. We continued down the highway, eventually coming out onto Interstate 25 at Bernalillo.

Greg got us to the airport in plenty of time for our flight on Southwest back to Dallas. A half-hour after the flight took off, Fred got a very nice picture as we flew over Eastern New Mexico near Tucumcari. This area of New Mexico is very isolated; I think the composition and coloring of the picture are very good.

This trip was a great deal of fun, and again I saw some areas of the country that were new to me. We got home about eight in the evening and had some dinner. Fred stayed over and went directly to work the next morning. I am beginning to like the West a very great deal; it is so different from the areas where Grant and I have been. Those areas all bordered on water, and thus had an entirely different flavor. They were pretty in their own right (Florida, California and the Gulf Coast) but the West has its own severe, forbidding beauty. I hope to see more of this area; Fred assures me that we will.

You can use the links below to go back to the previous day of the New Mexico trip or return to the Index for the trip to continue on through the photo album.

|

July 12, 1992: Taos and Rio Grande Gorge |

|

Return to the Index for the Santa Fe Trip |