|

October 23, 1993: The Lost Mine Trail and the Trip to Leakey, TX |

|

October 21, 1993: Fort Davis and Our Big Bend Campsite |

|

Return to the Index for Our Big Bend Trip |

Having already had some rest the previous evening, I was the first one up. I went ahead up to the facilities, and was munching on some cookies for breakfast when the other guys got up. The first hike on the agenda was the trail to a formation known as "The Window". Before we embark on that hike, though, let me orient you to Big Bend National Park- particularly if you've never been there.

Big Bend National Park

|

Because the Rio Grande serves as an international boundary, the park faces unusual constraints while administering and enforcing park rules, regulations, and policies. In accordance with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the park's territory extends only to the center of the deepest river channel as the river flowed in 1848. The rest of the land south of that channel, and the river, lies within Mexican territory. The park is bordered by the protected areas of Parque Nacional Cañon de Santa Elena and Maderas del Carmen in Mexico. Even so, the Rio Grande is so shallow in many spots the one can easily wade across, and so I can only imagine that border-jumpers are frequent.

During the early historic period (before 1535) several Indian groups were recorded as inhabiting the Big Bend, including the Chisos and Conchos Indians and the nomadic Jumano. Around the beginning of the 18th century, the Mescalero Apaches began to invade the Big Bend region and displaced the other Indian groups; the last Native American groups to use the Big Bend was the Comanches, who passed through the park along the Comanche Trail on their way to and from periodic raids into the Mexican interior. These raids continued until the mid-19th century.

|

Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the U.S. Army made military surveys of the uncharted land of the Big Bend, and various forts and outposts (such as Fort Davis) were established across the area to protect migrating settlers from Indian attacks. Ranchers began to settle in the Big Bend about 1880, and by 1900, sheep, goat, and cattle ranches occupied most of the area. The delicate desert environment was soon overgrazed.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, valuable mineral deposits were discovered and brought settlers who worked in the mines or supported the mines by farming or by cutting timber for the mines and smelters. Communities sprang up around these mines. Boquillas and Terlingua all resulted from mining operations. During this period, the Rio Grande flood plain was settled by farmers. Settlements developed, but they were successful only to the degree that the land was able to support them.

In the 1930s, many people who loved the Big Bend country saw that it was a land of unique contrast and beauty that was worth preserving for future generations. In 1933, the Texas Legislature passed legislation to establish Texas Canyons State Park. Later that year, the park was redesignated Big Bend State Park. In 1935, the United States Congress passed legislation that would enable the acquisition of the land for a national park. The State of Texas deeded the land that it had acquired to the federal government, and on June 12, 1944, Big Bend National Park became a reality. The park opened to visitors on July 1, 1944.

|

At left is an aerial view of Big Bend National Park, and I've marked some of the features that we'll see in the two days we'll spend here. Of course, we will be driving through the Chihuahuan Desert areas that form the largest portion of the park. The main park road arcs across the Chihuahuan Desert north of the Basin and down through that same type of area east of the Basin- down to Boquillas Canyon where the Rio Grande exits the park itself.

The Chihuahuan Desert also surrounds the Basin on the west and south, but on this trip we'll not be making any forays into either of these areas. We will visit Boquillas Canyon and the Langford Hot Springs, both of which are part of the Rio Grande Riprarian Zone.

The rest of our time will be taken up with hikes that we will be doing in the Chisos Mountains- a range contained entirely within the Park. The range is essentially circular, and the Chisos Basin lies in the middle of them.

The Chisos Basin

|

The park administers 118 miles of the Rio Grande for recreational use. Professional river outfitters provide tours of the river. Visitors can cross into Mexico at Boquillas Crossing to visit the same named town across the river, and many tourists do. (I might note that both the float trips and river crossings were severely curtailed beginning in 2002, and today it is much more complicated to do either, what with the restrictions imposed by the Department of Homeland Security.

Five paved roads are in Big Bend. Persimmon Gap to Panther Junction is a 28-mile road from the north entrance of the park to park headquarters at Panther Junction. Panther Junction to Rio Grande Village is a 21-mile road that descends 2,000 feet from the park headquarters to the Rio Grande. Maverick Entrance Station (where we came in) to Panther Junction is a 23-mile route from the western entrance of the park to the park headquarters. Chisos Basin Road is 6 miles long and climbs to 5,679 feet above sea level at Panther Pass before descending into the Chisos Basin. The 30-mile Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive leads from the Maverick-Panther road to the Castolon Historic District and Santa Elena Canyon.

The most-visited section of Big Bend is the Chisos Basin. Not only does it offer most of the upland hiking, but it is the location of the main park campground and the Chisos Mountain Lodge- Big Bend's National Park Hotel. The Lodge is usually full year-round, and the campground is almost always full during the spring, summer and fall. We have arrived at the tail end of the busy season, and while we had little difficulty finding a campsite, I learned that by 9PM on the day we arrived both the Lodge and the Campground were full.

|

For that purpose, I've included here an extract from the Big Bend National Park brochure map; we picked up one of these brochures when we registered our campsite here in the Basin.

On that diagram, I have marked the two hikes that we did here in the Basin; we did the Window Trail today and we will do the Lost Mine Trail tomorrow. You can also see the various services provided here in the Basin, as well as the park road to the north, the road into the Basin, and the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive down the west side of the Chisos Mountains.

Now, let's embark on this morning's hike down to The Window.

The Trail to "The Window"

|

|

Although the night was quite chilly, with the sun up things are warming up nicely. I have decided not to take my jacket- a wise decision, as it turned out. The day was also crystal clear- ideal for hiking. Actually, this trip was a lucky one. Up until Wednesday afternoon, most of Texas had been very, very wet. Dallas had about ten inches of rain in the previous four or five days. But just as we left town Wednesday afternoon, the skies began to clear, and by the time we got up in Midland on Thursday, the weather had totally cleared out. The weather remained good until the day we left the park, when it began to get cloudy again.

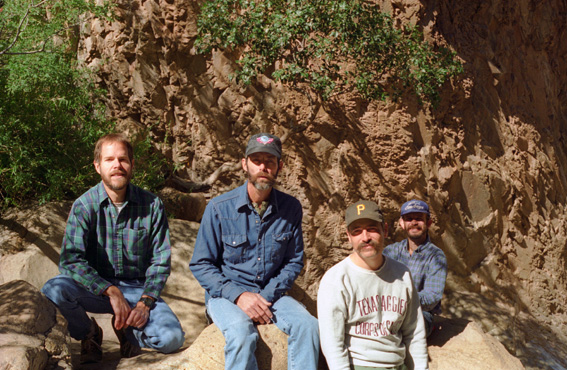

Fred had his panoramic camera with him, and he took a nice picture of us just before we began our hike:

|

I was looking forward to hiking down to the Window, described in the trail guide as "a large rock canyon that cuts through the Chisos Mountains rim, allowing drainage from the Basin to the Chihuahuan Desert. The V-shaped Window frames panoramic desert views and forms a perfect silhouette for the colorful Big Bend sunsets—the hike itself offers excellent opportunities to view wildlife, plant life, and the fascinating geology of the Chisos Basin."

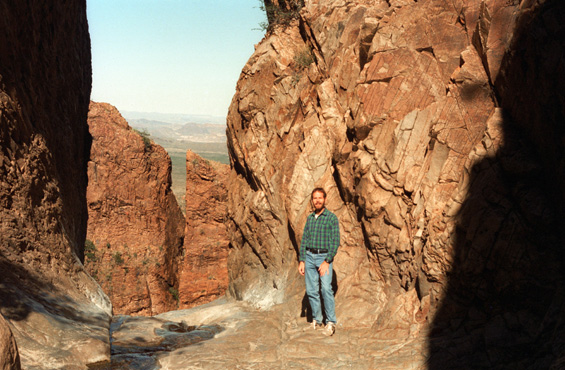

Me at the Window Trailhead |

(Picture at left) Since Fred's 35mm camera was in the shop, he used mine to take the pictures he wanted- in one of which he posed me behind this sign. We started off down the trail- unusual for the hikes Fred and I have done in that the outbound part is downward and the return is all uphill.

(Picture at right) |

Starting Out on The Window Trail |

As we walked down the trail, we were all interested in looking at the various flora along the trail. Frank and Joe are as interested in horticulture as Fred is, and all of them collect the odd plant or flower. Fred keeps them in his greenhouse, while Frank and Joe plant them around their farm house in Leakey. I learned a lot just from walking with them. One thing I have learned is that just about everything is in the sunflower family (inside joke).

|

|

One thing we learned at our trailhead was that this trail has two starting points; there is another up by the Chisos Mountains Lodge. Our starting point reduced the distance about a mile and the elevation change by about 300 feet. The trail descends all the way to the Window, so it was an easy hike going out (and not that bad coming back).

On the Trail to The Window |

(Picture at left) Here, as the basin narrows, the trail climbs over the course of the stream that flows out of the park. You can see that steps have been carved into the rock; anything else would wash away in a heavy rain. The sun is still not high enough to banish all the shadows along the trail. Rains are frequent enough such that plant life doesn't grow below the line that is just above our heads.

(Picture at right) |

In the Oak Creek Streambed |

As you can see in the two pictures above, we have left the relatively flat environment of the Basin (and the improved dirt trail) and are now walking down through Oak Creek Canyon- with Oak Creek at the bottom. We were lucky in that there was enough water flowing through the creek to provide interest and a neat brook-like sound as we walked, but not so much to make the creek crossings or our stop at the Window itself dangerous.

Waterfalls Along Oak Creek |

(Picture at left) We encountered this series of waterfalls, and stopped to admire them. Fred likes water features, so he was interested in capturing this scene. He has been here before, but I am not sure if there is more or less water now than the previous time. I would like to see what this area looks like with a good deal more water flowing through. Right now, the footing is easy, but if there were a lot of water the trail would be much more difficult.

(Picture at right) |

An Oak Creek Waterfall |

It was great fun hopping from rock to rock in order to cross the stream. Approximately the last quarter-mile of the hike traversed the slickrock canyon where footing becomes more difficult; there were rock steps, slippery wet surfaces, and several stream crossings. Making our way across the water and polished rock, we marveled at the spectacular scenery before reaching the top of the pour-off. What an incredible vista we found there!

|

|

While you are in the basin, your views are circumscribed by the Chisos Mountains. Only from this point can you see through that ring of mountains to the Chihuahuan Desert beyond and below. From here, you are looking generally towards Santa Elena Canyon, and northern Mexico lies just on the other side of the Rio Grande which in turn is beyond the light-colored mesa you can see through the Window.

This vista was incredibly beautiful, and I never got tired just standing here and looking at it. That is why there are a number of pictures taken from this point or other points close to it.

The appropriately named "Window" offers a view into the desert below and beyond, its high walls towering above the polished rock that is the pour-off. A sign posted nearby suggested that one not approach the edge too closely: "The rocks are slick and a fall to the desert 220 feet below would be fatal".

At The Window All around us are interesting cacti and other plants, and all of us spent some time down here climbing around looking for unusual specimens. There are a number of cacti that grow nowhere but within the confines of the basin here in Big Bend National Park. |

Me at The Window This will give you a good idea of where I was standing to take the pictures through The Window. The drop-off is just where you see the water disappear, about ten feet to my right. When I was taking the previous pictures through The Window, I was standing on that whitish area to my right, which left me about six feet or so before the drop-off. |

Now, had this area been wet, I never would have ventured this far out, because once you start sliding, there is nothing to stop you. It is this small opening that is the only outlet for all the water that might fall on or be generated in the thousands of acres that form the Basin. I would not want to be here during a thunderstorm.

The Lowest Waterfall on Oak Creek |

(Picture at left) Here, the rocks have been scoured by the water and there is no vegetation. But just a few feet back up the trail, cactus and other plant life grows almost down to the stream bed itself.

(Picture at right) |

Santa Elena Canyon Seen Through the Window |

I find this landscape particularly beautiful, but with a beauty different from the oceans, the heavily-wooded Appalachians, the snow-capped Rockies, or any other area that you can think of. I have appreciated every trip Fred and I have taken into the American West. The land of the Chihuahuan Desert is mostly useless, but that doesn't detract from its stark beauty.

Santa Elena Canyon and Chihuahua State from the Window I have just changed position a bit to try to see more of the landscape through this natural window in the basin wall. |

A View Through the Window Notch We've moved back along the trail a ways and I wanted to try to get some of the plant life into the picture. While I was climbing around, I found some excellent cactus samples (which I would loved to have taken were it not for the regulations against that). |

After spending a good deal of time down close to The Window, we began the hike back up to the campsite, but we were still in the rocky streambed of Oak Creek. All of us did some looking around for various plants life. Even though I don't know the significance of what I see as far as plants are concerned, I still enjoy looking at the incredible variety that exists here. I took my camera with me as I clambered up about forty feet above the stream bed to see if I could find some unusual specimens. I did find some ferns and a very interesting variety of giant clover. What made this clover so interesting was more than just its size (each leaf was about an inch across), but the fact that the underside of the leaves, which were a normal clover green on top, was purple. I brought a sample down to the guys, none of whom had seen that particular variety before.

|

|

All of us were looking around for cacti and other plants of interest. You can't see much, but you can pick out some of the common prickly pear cactus at the bottom of the picture. Incidentally, I read on the way home from Frank and Joe's ranch that there is a variety of prickly pear that grows only in the basin area of Big Bend National Park, but I have no way of knowing if this is some of it.

|

Since the hike back to the trailhead was all uphill, we took our time, and did some exploring up and down the rocky hillsides and clambered around in the streambed of Oak Creek.

|

|

Having lost Grant just a couple of years ago, I am probably more concerned than most for the well-being of other of my friends in the same position- like Joe. He probably gets tired of everyone being solicitous all the time, but that's the way people are. Joe has had some of the same things Grant did, but treatment has advanced greatly and he is able to get past them. He seems to be handling things very well, and hasn't had anything major in a couple of years.

I certainly can't put myself in the category of his best friends, the category occupied by Frank, Fred and others, but maybe my concern can come from a second tier- people he knows and whom he knows are concerned about him. I will never know him as well as Fred does, but that doesn't stop me from being continually a bit worried about him, just as I was always worried about Grant, even at the times when it seemed as if he was getting along swimmingly. (NOTE: It's 2016 as I am creating this particular page, and everyone, including Joe, is doing absolutely fine.)

We continued the hike back, re-entering the Basin itself and walking alon gthe improved trail with good views of the Chisos Mountains ahead of and around us. We did have one surprise encounter on the way back.

|

As we ascended back to the campsite, we passed this dry wash, and Fred heard some noises coming from it and with his eagle eyes spotted these Javelina grazing in the leaves of the stream bed. Javelina are peccaries, who are related to deer, although it looks as if they are related to pigs instead. I was able to get fairly close to them before I began to spook them. I thought it was me, but when I looked around I saw that two other hiking parties had stopped to see what we were looking at, and a few of those people were climbing down into the stream bed, being rather less unobtrusive than I was.

|

Many of the other animals have moved away from me and the others, but I was able to get a bit closer to these two. To me, they look like a cross between anteaters, rats and pigs. After checking my program on mammals, I find that the habitat of the peccary only reaches into just the lower part of the Southwest in this country, and actually the map looks as if they might be not much more prevalent than in this particular area.

The return hike was just as beautiful as the descent into the canyon; excellent views of Casa Grande and Emory Peak on the way back added another dimension to this very neat hike.

The Drive to Boquillas Canyon

|

Passing Panther Junction, we drove another twenty miles through the Chihuahuan Desert to the southeast, past Rio Grande Village and then eastward along the north side of the Rio Grande to the trailhead.

Along this drive, we had an opportunity to see much of the landscape of Big Bend National Park that lies outside the relatively verdant Chisos Mountain Basin.

|

|

At the main park road, we turned right(east) towards Panther Junction. We stopped at the visitor center to buy our park entrance sticker and wander through the Park store. We saw some interesting CDs, and Fred bought a couple. I got some stamps for postcards in the Post Office, and we walked through the cactus garden outside the visitor center.

Looking Back at the Chisos Mountain Basin Those mountains form part of the rim of the basin itself. |

A tunnel on the Road to Boquillas Canyon In the far background are the mountains that form the eastern boundary of the park. |

After we passed through the tunnel, the guys saw some interesting cactus, along the roadside. We stopped to look at it and then continued down past Rio Grande Village to the trailhead for the Boquillas Canyon hike.

The Hike Into Boquillas Canyon

|

Just over the crest of the outcrop, we encountered three Mexicans selling rocks and minerals that they said they had brought across the river from caves on the Mexican side. That is undoubtedly true, as there are no reported caves in the park itself. They had some nice stuff, and we planned to stop and look it over on the way back. Frop the top of the outcrop, the remainder of the trail is easy as it descends to follow the river on fairly level ground.

|

|

As we entered the canyon proper, the walls began to close in, and on our side of the river there was a trail and maybe forty feet of fairly level ground, sloping up to the canyon walls on our side. On the Mexican side of the river, there was almost no land at all- just sheer cliffs dropping right down into the water.

|

|

This is the closest I have been to Mexico in a long time. This doesn't seem like much of a border, and it is hard to see how we could ever keep people from coming across at this point and entering the United States illegally. But one thing that keeps much of that from happening is that there are no towns close to the other side of the river here; border-jumpers would have to go a long way cross-country to get here. Once across, illegals would then face the problem of getting north; there are only two roads north from the park, and both have border control stations along them. There are also lots of Border Patrol agents who regularly monitor the land off-road.

Still, if the jumpers planned ahead and were in good shape and very motivated, it is hard to see how the flow of aliens could be stopped. After all, the three Mexicans selling rocks had gotten across with all their goods, and could just jump in someone's vehicle and take off.

|

Fred also had me take basically the same picture, but this time using Fred's panoramic camera. Vertical panoramas are hard to put in these album pages at a size that enables you to see them the way we might intend. So, as I've done for other verticals, this one is in a scrollable window below (just to the left of the actual image):

|

It was really interesting being down here by the Rio Grande in the stark beauty of Boquillas Canyon; one usually thinks of the Rio Grande being a major river, but it turns out that at least here, it is really kind of small. But it is pretty- especially set against the rocky canyon.

|

|

When I finally joined the other guys at the top of the dune, I snapped the picture at left of the three of them. On top of the dune, there is a depression before the dune meets the cliff face, forming a natural bowl. I am in the bottom of that bowl looking up and out over the dune. I thought I had allowed for enough light to get everybody's faces, but again I was wrong, and had to lighten things up in "post production". The cliff opposite is in Mexico.

After standing around for a few minutes, someone yelled "Geronimo!" and we all ran down the dune, which was the whole point of coming this far up. It is a challenge to run down the dune without losing your balance and falling over, but we all did it.

On our way out of Boquillas Canyon, we stopped so Fred could take another panoramic picture:

|

We stopped back by the rock salesman and each of us bought some crystals. Frank and Joe ended up trading some sodas for more rocks, although the Mexicans wanted Frank's hat, Fred's backpack and something else of Joe's, but basically we each spent about $5 with them. Then we were off to Rio Grande Village and Langford Hot Springs.

The Langford Hot Springs

|

Although other homestead claims on the site had failed, Langford, his wife Bessie and his 18-month-old daughter set out for the site, discovering that it was already occupied by Cleofas Natividad with his wife and ten children. Initially considering the Natividads squatters, the Langfords developed a cooperative relationship with them. Langford took a 21-day treatment of drinking and bathing in the spring waters, reportedly regaining his health.

The site was the first major tourist attraction in the area, predating the establishment of the national park. Before the Langford's development, a small stone tub had been excavated in the local stone for bathing, with a dugout that was renovated by the Langfords as a residence. The Langfords later built an adobe house, a stone bathhouse, and brushwood bathing shelters. The Langfords left in 1912 when bandits made the area unsafe. When they returned in 1927 they rebuilt the bathhouse, but with a canvas roof. They also built a store and a motor court, consisting of seven attached cabins.

|

The historic district includes petrogylphs left by native American visitors. The springs were visited by Pedro de Rábago y Terán in 1747, who found Apaches farming the area. In later years the Comanche Trail passed nearby. The hot springs remain, at a temperature of 105 degrees Fahrenheit, and may be used for soaking.

Boquillas Hot Springs was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 17, 1974.

As I said above, there were a lot of cars in the parking lot when we arrived, so the four of us tramped up in the hills west of the lot to hunt for any unusual cactus we could find. (Fred and Frank did find some small specimens that they wanted, and so they surreptitiously put them in Fred's backpack, and they eventually found new homes in Leakey and Van Alstyne.) As it turned out, there were also very good views from up here, so the delay turned out to be worth it for another reason as well.

Rock Formations on the Other Side of the Rio Grande As we climbed the hills just beside the Rio Grande, this view of the nearby hills and the distant Mexican mountains offered itself. I though the clearly-defined layers in the obviously sedimentary rock were interesting. |

Looking Downstream Along the Rio Grande Note the general nature of the vegetation here, and the course of the river below. Mexico is across the river and in the distance are the Sierra del Carmen mountains in Mexico.I enjoyed looking at all the different kinds of plants that there were. |

Fred also did one of his panoramic shots from up here:

|

|

Just in front of that is a long, low building. This an old spa that was built for the people who came to the hot springs. It is like a small motel, with small, simple rooms where people could stay. There were about fourteen rooms in the building. In front of that, towards me, is the old Post Office for Hot Springs, Texas. It is no longer in use (if it ever was an official Post Office).

Then you see the parking area and off to the right one of the small creeks that runs into the Rio Grande. Then, just above the parking area, the ruins of an old house that was built for the people who ran the hot springs. Finally, the hills on which we are standing and more of the vegetation that is so common. The trail to the hot springs leads by the long building and then about a quarter of a mile to the banks of the Rio Grande.

I took another picture of Joe and Fred coming down from the hills and our cactus expedition. Even this small creek that joins the Rio Grande has its own beauty.

When we got back down to the parking area again, we noticed that many of the cars had disappeared, so it looked as if we should head on downriver to the hot springs for our soak.

|

From the trailhead, we embarked on half-mile trail to the hot spring. We could have taken a shorter trail along the river, but we thought we would take part of the upper trail on the hillside, and indeed there were better views there. The path to the hot springs took us by some pictographs, but none of them were very interesting, and many of them had been spoiled by modern graffiti. Eventually, we descended a wash to the Langford Hot Springs.

Hot spring water is considered old water, fossil water, ancient and irreplaceable. Heated by geothermal processes and emerging at 105° F., the water carries dissolved mineral salts reputed to have healing powers. The therapeutic value of heat has long been touted as a remedy of both body and soul.

Like anything else, there were oodles of advisories posted by the springs. "Be aware that some hot springs can burn you either with the scalding effects of heat or the caustic nature of the water chemistry. Use caution when bathing and limit the exposure of children to the warm waters".

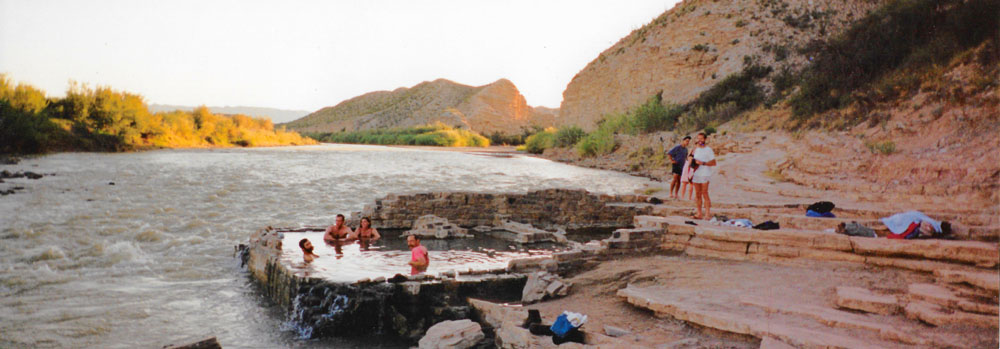

The hot springs bubble right up into the Rio Grande here, and many years ago the discoverers built some rooms right on the Rio Grande to contain the hot waters and provide a place for people to take the waters. Over the years, the walls of the structure have deteriorated and collapsed, until only these very low walls are left. They are sufficient to contain the hot water until it spills over them into the river. Fred says he has been here when the river has been so high that its water has washed into the hot springs so much that you could hardly find the hole up through which the hot water comes. But today the river is about a foot below the walls.

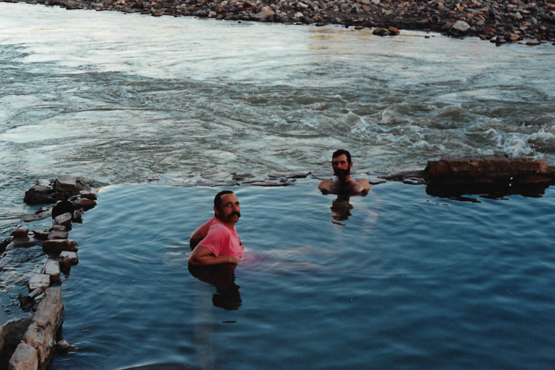

Frank and Joe in Langford Hot Springs I stuck my hand into the river water, and it was quite cold. The water from the hot spring is about 100 degrees- quite pleasant. |

The Rio Grande Rushing by Langford Hot Springs This view looks downstream along the Rio Grande at the hot springs. |

The panoramic picture that Fred took will give you the best idea of what the hot springs were like, and you can see the entire enclosure, the Rio Grande, and a few other folks who were just getting ready to leave (at which point we were pretty much by ourselves):

|

The last two pictures today were also taken here as we were soaking in the hot springs:

Fred, Frank and Joe in the Hot Springs The only bad thing about the hot springs was the fact that there was a lot of algae growing in the tepid water on the rocks and things. The algae is washed off periodically when the river intrudes. |

The Rio Grande I walked a bit down the riverbank and up onto a rise to get this picture of the Rio Grande flowing eastward. |

The soak in the hot springs was refreshing, and we spent some time there just relaxing and talking. When we left, we said a few words to two people who seemed to be looking for fossils. We got back to the trucks and headed down to Rio Grande Village to take some showers, but when we got there we found that the showers were already closed. So to end the day we went on a short nature walk on the Rio Grande overlook trail. Fred wanted to show us some natural rock depressions where the Indians had ground corn just like in a mortar and pestle. We got back to the campsite after dark and Fred gave us our choice of chili or stew again. Joe didn't think that chili would set well with him, so we had stew again and, as usual, it was delicious. By the time we finished and cleaned up, it was time to hit the sack. The new tent and sleeping bag were very comfortable, and in no time at all we all were asleep.

You can use the links below to continue to another page for our Big Bend trip or to return to the trip index so you can continue though the photo album.

|

October 23, 1993: The Lost Mine Trail and the Trip to Leakey, TX |

|

October 21, 1993: Fort Davis and Our Big Bend Campsite |

|

Return to the Index for 1993 |