|

June 27, 2003: Western Trip, Day 7 |

|

June 25, 2003: Western Trip, Day 5 |

|

Return to the Index for Our Western Trip |

|

June 26 Our Canyonlands Campsite The Peekaboo Hike Wilson Arch Arches NP (Part 1) Staying in Moab, UT |

It's Thursday now, and we'll be breaking camp, doing another hike here in Canyonlands, and then heading over to Arches National Park for a visit. We'll be staying somewhere in Moab, Utah, tonight and, at some point, getting my windshield fixed.

|

I've also marked the dirt road that lead to yesterday's trailhead at Elephant Hill, and also the route we walked to get to the trailhead for today's hike on the Peekaboo Trail.

|

The campsite was really a good one, with some trees to shade the tent. Rather than being out in the open, the back of the site was bordered by a rock wall, and so it felt very safe and enclosed. If you'll click on the thumbnails below, you can see the pictures that we took this morning here at the campsite:

|

You can return to the page index or continue on to the next section.

The Peekaboo Hike (Big Spring Loop)

|

This modification turned what was billed as a "strenuous" hike into one that was even more so, but since we had the time, and wanted to see as much as possible, we thought that taking ourselves to the point of total exhaustion would be worth it. We did, and it was.

|

The hike began at the Squaw Flat Loop "A" Trailhead, at the Squaw Flat Campground. We could have done the hike either clockwise or counterclockwise; we chose to go "against the flow" and generally proceed in a counterclockwise direction around the borders of the three canyons.

|

One reason I liked the hike was that some scrambling was required as we made our way up these rugged, desert canyons. Although vegetation grows in the sandy soil in the canyon bottoms, much of the hike is on barren slickrock. The hike was also a great introduction to the landscape of the Needles, connecting three canyons for a loop across varied terrain.

|

|

Of course we took a great many pictures- about as many along the first half of our hike as along the second half, and I have taken these pictures and put them into the slideshow at right.

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at right and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

I thought about trying to key them to an aerial view or a map, but doing so wouldn't add to the beauty of Canyonlands. So just go through the slideshow and walk through the Canyonlands with us.

When we returned to the car, we were tired and thirsty, but we were extremely satisfied with ourselves for trying to see as much as we possibly could. It would be nice, though, to sit in an air-conditioned car for a while on our way to Arches National Park.

You can return to the page index or continue on to the next section.

|

To get there, we got back in the car at the trailhead, and headed back out of Canyonlands the way we'd come- along Utah Highway 211. This took us back by Newspaper Rock and back out to US 191 just north of Monticello. Then we turned north on that highway.

The highway winds through some pretty stark landscape, but the land has its own beauty. One noteworthy vista was this black mesa. It displayed the same columnar structure that we'd seen before in the West and which most people associate with formations like Devil's Tower in Wyoming. This rock looked blackened, as if there'd been a fire, but the color was entirely natural. It was starkly beautiful.

The turnoff for Wilson's Arch was about twenty miles up the road.

|

According to the sign at the pulloff near the arch:

"Wilson Arch was named after Joe Wilson, a local pioneer who had a cabin nearby in Dry Valley. This formation is known as Entrada Sandstone. Over time superficial cracks, joints, and folds of these layers were saturated with water. Ice formed in the fissures, melted under extreme desert heat, and winds cleaned out the loose particles. A series of free-standing fins remained. Wind and water attacked these fins until, in some, cementing material gave way and chunks of rock tumbled out. Many damaged fins collapsed like the one to the right of Wilson Arch. Others, with the right degree of hardness survived despite their missing middles like Wilson Arch."

We got out of the car and walked up underneath the arch, marveling at the graceful pedestal that was supporting it. It was hard to imagine the forces that create such a wonder. From up underneath the arch itself we could look back down the hill and see a long stretch of US Highway 191 leading north to Moab. We hung out at the arch for a while before getting back in the car and continuing north towards Moab and Arches National Park.

You can return to the page index or continue on to the next section.

An Afternoon Visit to Arches National Park

Getting to Arches National Park

|

First, we secured a hotel room for the night at the local motel whose name I have since forgotten. It wasn't a chain, but it was a nice place and they ended up giving us a great recommendation for dinner.

The other thing was that I stopped by the local Safelite Auto Glass office to find that it would be best if I brought the car in first thing in the morning to minimize wait time for a windshield repair, and so that is what we planned to do.

Then we drove up to the entrance to Arches National Park.

The History of Arches National Park

|

The first European settlement of Southern Utah arose from the colonizing efforts of the Mormon Church. When conflicts with the Indians ended, Moab was settled permanently in the 1890s by ranchers, prospectors, and farmers. One settler, John Wesley Wolfe, a veteran of the Civil War, built the homestead known as Wolfe Ranch around 1898, seeking good fortune in the newly established State of Utah. It is located in what is now Arches National Park on Salt Wash, at the beginning of the Delicate Arch Trail. Wolfe and his family lived there a decade or more, then moved back to Ohio. Their cabin remains.

One of the earliest settlers to describe the beauty of the red rock country around Arches was Loren “Bish” Taylor, who took over the Moab newspaper in 1911 when he was eighteen years old. Bish editorialized for years about the marvels of Moab, and loved exploring and describing the rock wonderland just north of the frontier town with his friend, John “Doc” Williams, Moab’s first doctor.

Word spread. Alexander Ringhoffer, a prospector, wrote the Rio Grande Western Railroad in 1923 in an effort to publicize the area and gain support for creating a national park. Ringhoffer led railroad executives interested in attracting more rail passengers into the formations; they were impressed, and the campaign began. The government sent research teams to investigate and gather evidence.

On April 12, 1929 President Herbert Hoover signed the legislation creating Arches National Monument, to protect the arches, spires, balanced rocks, and other sandstone formations. On November 12, 1971 congress changed the status of Arches to a National Park, recognizing over 10,000 years of cultural history that flourished in this now famous landscape of sandstone arches and canyons.

Arches, along with other of the "crown jewel" parks, is exquisitely beautiful, and it well-deserved a second visit from us. The first time we were here, we spent a full day in the park; this time, we'll spend this afternoon and also the first part of tomorrow here. For this afternoon, we will stop at a few of the formations we missed the first time we visited, and tomorrow we will visit some more of them.

A Map of Arches National Park

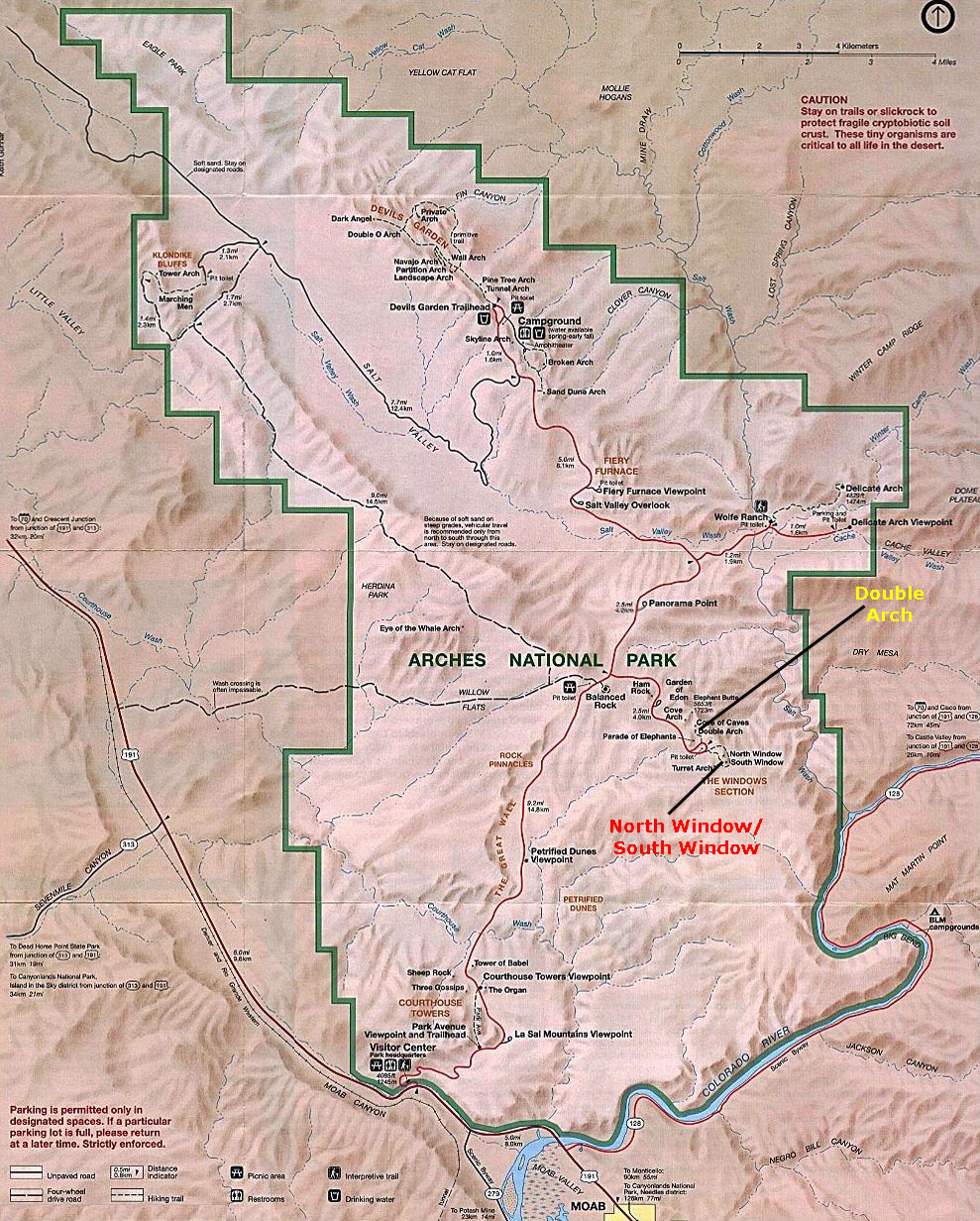

Like most of the national parks, the parts of Arches that are most often visited occupy a small fraction of the total park area; most of the park is relatively unexplored by even the serious park visitor. The same was true of Canyonlands; most visitors just drive the short park roads or perhaps take short hikes from the campground. We probably did more hiking there than 99% of the people who visit.

But so you can get an idea of the lay of the land here at Arches National Park, I've made a copy of the park map and put it in a scrollable window below. You can use that map to follow us on our visits to some of the famous landmarks here; you will see that almost all of them are right on the main park road (although some require a healthy hike from that road to get to).

|

The North and South Windows

|

There was a short trail that led up to the Windows from the nearby parking area, and we were able to get right up to them. Below are some thumbnails for views of the separate arches and their outward bases; click on them to view:

|

|

Double Arch

|

|

|

We went up the rock amphitheater behind the first arch up to the adjoining span, a smaller 67-foot wide and 86-foot tall arch. Geologists believe this impressive span began as a pothole of water on the surface overhead. The collected water slowly broke down the rock, forming an alcove, which eventually created both arches. Science aside, the twin arches seem like an improbably natural wonder, created solely to amaze. The inspiring configuration went by a few other names over the years, like Double Windows, Jug Handles, and Twinbow Bridge. Whatever anyone else calls Double Arch, I call it impressive. If you visit Arches, don't miss this short hike!

That was all we really had time for this afternoon, but we will be back tomorrow.

You can return to the page index or continue on to the next section.

|

Then, tuckered out from hiking this morning and this afternoon, we hit the sack.

You can return to today's index

or use the links below to continue to the album page for different day.

|

June 27, 2003: Western Trip, Day 7 |

|

June 25, 2003: Western Trip, Day 5 |

|

Return to the Index for Our Western Trip |