|

May 11, 2016: Big Bend- Santa Elena Canyon |

|

Return to the Big Bend Trip Index |

Today, we will be doing things in and around Fort Davis. We will be visiting the Fort Davis National Historic Site, and also doing some hiking at the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center and Botanical Garden about six miles south of town. This will be our last day here in West Texas; Fred and I will be heading back to Dallas in the morning, and everyone else will be returning to San Antonio.

The Indian Lodge Resort in Davis Mountains State Park

|

Indian Lodge is probably the most interesting and historic hotel Fred and I have ever stayed in. Built in the 1930s, it opened to the public in 1939. The lodge resembles a multilevel pueblo village. The Civilian Conservation Corps built the first section of the lodge, and guests can see their work today, in the original interiors and furnishings. It looks much different today than it did at the time of its construction:

|

Let's take a tour of the property, and also learn a bit more about its history. When you come down the park road, there is a turnoff that brings you up the hill to the parking area at the south end of the property.

|

The office is in the center of the area, right off the parking lot. To the left of the office there is a walkway that leads back into the lodge complex; it ascends a set of stairs to bring you into the open courtyard area that we'll visit in a moment.

On your left is a two-storey structure; on the ground floor there is a meeting room and upstairs is the Black Bear Restaurant. The restaurant is actually reached from a stairway up from the courtyard on the other side of the building from where I was standing when I took the picture at right.

I walked up to stand on the walk between the office and the restaurant buildings, and then turned to my right to photograph the office and beyond it the row of original rooms; you can see that view here.

Here are a couple of other pictures that we took right here by the office:

The Walkway Leading Up to the Courtyard |

Me, Sitting Outside the Office |

Let's head down the walkway by the office and go up the stairs to the open courtyard in the center of the complex. When we did that, we turned to photograph the stairway back down to the office. In that picture, you can see the Black Bear Restaurant at the right.

|

The courtyard area is basically a large patio with a number of chairs and benches along with a firepit and various planters. From this courtyard, one can go up the stairs to the Black Bear Restaurant, follow various walkways to many of the guest rooms, and enter the common area building where we will go in a moment. Here are some other views of the courtyard:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

Off to the right from the courtyard, in the same building as the office, there was a great room, or common room. It is similar in function to a clubroom, or perhaps the living room at a B&B- it is where guests can gather outside their rooms to socialize.

|

There were fireplaces at both ends of this large room, and more of the wood furniture that is original to the lodge. This was a bright, open room, even though the wood construction might have made it feel heavy.

Behind the fireplace in the picture at right there were stairs up to a reading nook. It was a small room, covering maybe a third the area of this big downstairs room. The reading nook and the common room were had the only padded furniture I saw at the lodge. The overstuffed leather sofa up here in the reading room was extremely comfortable, and it made the room a great place to go to relax. There were windows looking out on the courtyard and out over the pool area, and the room had its own small fireplace.

Back downstairs in the common room, Fred was interested in the pictures hanging all around the room that told at least part of the story of Indian Lodge.

|

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

I came to the reading nook early both mornings we were here. It was a nice morning walk from the room, and it was also a great spot for a view of the sunrise.

From the common room, let's go out the doors on the east side of the room. This will put us on a balcony that overlooks the swimming pool. In that picture, you can also see more of the first row of rooms built in the 1930s. The Lodge has grown in size through the years, although the last rooms were added in the late 1950s. From this balcony guests also have nice views of the Davis Mountains. In that last picture, which looks generally north, you can see some of the trails that wind through the mountains, past the lodge and down into the campground. Fred and I did some of those trails on an earlier trip here some years ago.

|

Our room and Nancy's room were next to each other, but the rooms were oriented differently. You can see the door to Nancy's room here; the door to our room is nearer the camera, just this side of the bench. In the corner of the walkway outside our rooms was a table that we sat at in the morning, having coffee and planning the day. Here are some more photos of our rooms and the area outside them:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

This morning, the six of us had breakfast in the restaurant (Ron and Prudence ate at their bed and breakfast). We all met up in the common room and then we walked through the courtyard and up the stairs to the Black Bear Restaurant. There was a nice view of the courtyard from just outside the doors to the Black Bear Restaurant, up on the second level. We had a really nice breakfast, and while we were waiting for our meals, I took a series of pictures of the sixty-foot mural on the wall of the restaurant, and stitched them together so you could see how neat it was. Use the scrollable window below to have a look at the mural:

The Indian Lodge is probably the most historic and unusual place that Fred and I have stayed in. It isn't the oldest by any means- the Gage Hotel was older, certainly. But while we have hiked and camped in parks whose trails and campgrounds were built during the Depression by the CCC, we have never stayed in a lodge with that same history.

|

|

Here are a few other pictures we took that are worth including in this album:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

To finish off our pictures of Indian Lodge, here is a panorama that I constructed out of three individual photos:

|

When we were done with breakfast, we headed off to reunite with Ron and Prudence.

At the Verandah Historic B&B

|

We drove into town and over to the Verandah on Court Street. It took us a while to locate Prudence and Ron; they were staying behind the main house in a private cottage. We found Ron there, but it took us a few minutes to locate Prudence, as she was out walking Jax.

I am not sure just why Ron and Prudence were dissatisfied with the B&B; I think it was a combination of the room being way too small for the three of them and also the air conditioning not working very well. They already had plans to move to a larger space at the Limpia; actually, they'd investigated it last night. While Ron took the walkway into the main house to settle their bill, we carried their luggage out to Nancy and Karl's car; they had arrived just a few minutes after us (along with Mike and Vickie).

We took a couple of other pictures here at the Verandah- both of them of animals. I took a picture of the pet pig they kept out back (perhaps another reason why Prudence and Ron didn't like the B&B) and Fred had the good fortune to spot an actual live Horny Toad (apropos, since we'd just taken the picture of the fake one only 30 minutes before) and get a good picture of it before it scampered off into the bushes:

|

|

We followed Nancy and Karl as they drove Ron and Prudence over to the Limpia Hotel, and we waited until they had secured their room and put their luggage inside. Then we piled back into our cars and drove the ten blocks or so to the Fort Davis National Historic Site.

The Fort Davis National Historic Site

Entering the Fort Davis National Historic Site

|

Troops stationed here played a major role in the campaigns against the able Apache chieftain Victorio, whose death in 1880 terminated Indian warfare in Texas. Today the remains of Fort Davis commemorate a significance phase of the advance of the frontier across the American continent.

In return for the picture above, left, I took a picture of Fred at the entrance marker for the historic site. There were also two other markers along the walk to the visitor center, and I thought you might want to read them. The first was the official history marker for Fort Davis, and the other was the plaque placed in 1960 when Fort Davis was named a National Historic Landmark. Just before I crossed the bridge I thought that this would be a good place for me to create the first panoramic view of the Fort Davis site. It took a bit of stiching, but here it is:

|

The Fort Davis National Historic Site Visitor Center

Me Outside the Visitor Center |

Fred Inside the Visitor Center |

Before we went out to walk all around the historic site, Fred and I took the time to wander through the museum area of the Visitor Center. It was arranged in a "U"-shape, beginning and ending at the front desk and gift shop.

|

|

Below is another slideshow with more of the pictures that we took here in the museum. As with the slideshow at left, you can move through the pictures in this one by clicking on the forward and backward arrows in the bottom corners of each picture:

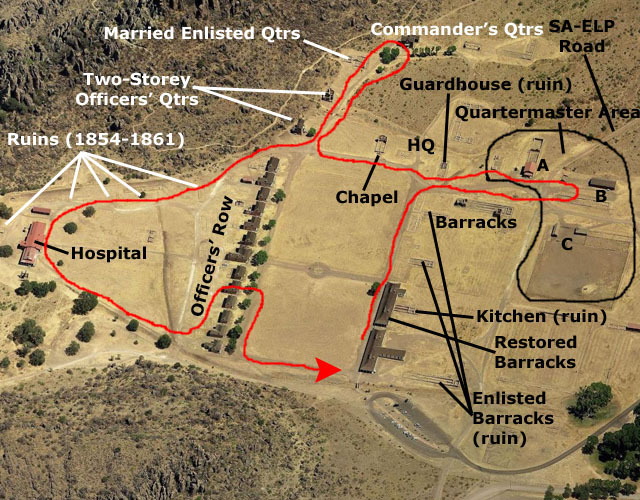

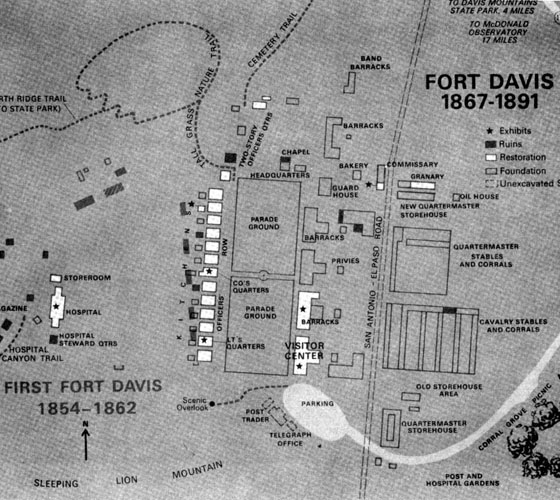

We picked up a site guide in the museum that we could carry around with us, and we all went next to the theatre to catch the next showing of the informative movie. Then we went out to have a look around Fort Davis. To help orient you as we walk around the area, I have put both an aerial view of the fort as well as a diagram of Fort Davis as it evolved while it was in use. I will mark some of the places we stopped and the route we took on these images:

|

|

The Barracks at Fort Davis

Looking Northwest Across the Parade Ground from the Visitor Center |

They also are home to the story of the American experience, from its precontact cultures down to the late-twentieth century. As the steward of Fort Davis National Historic Site, the National Park Service engages constantly in the discussion of the meaning of the far western frontier. In addition, its staff, volunteers, and Friends group must preserve a highly valuable architectural and historic resource to meet the needs of visitors seeking an accurate portrayal of what is often described as the "best example of the frontier military in the Southwest." The history of Fort Davis falls into two distinct periods. The first spans the time from its first occupation in 1854 to the departure of U.S. Army troops in 1861 at the beginning of the Civil War. The second period begins with its re-occupation after the war in 1867 until its closure as an active military fort in 1891. For the first part of our tour, we will be focusing on ruins and restored buildings dating from that second period. We will get to the buildings from the earlier period a bit later on in the day.

All of the original buildings that were used as barracks beginning in 1867 here at Fort Davis have been long since ruined, but there was a recreation of what they looked like in a new building just north of the Visitor Center.

|

|

The new building was actually two exhibits. At one end were the recreated barracks, while at the other were exhibits of some of the equipment and some of the techniques that the soldiers manning the post would have used and practiced.

|

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

The return of Union forces to west Texas took some time, as the war in the East moved toward closure in 1864-1865. The departmental commander of New Mexico, Brigadier General James H. Carleton, had sent down from Santa Fe in September 1862 that found Fort Davis mostly in ruins, with furnishings and supplies sold by the CSA to the Hispanic residents of the border. Yet the quickened pace of travel along the San Antonio-El Paso road after the war brought a new round of Indian raiding, which the Army met in 1867 by reopening Fort Davis. Two years later the post had become the headquarters for the Presidio command of the 5th Military District of Texas, and the fort would remain in operation throughout the height of the Indian wars of the 1870s and 1880s.

|

Here are three pictures Fred and I took of each other and the ruins of the enlisted barracks:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

By orders of the Department of Texas, the Army staffed Fort Davis in 1867 with companies of the Ninth Cavalry, composed of black soldiers recruited for the segregated units created after 1866 to permit freed slaves to serve their country in uniform (as they had done in the latter stages of the Civil War). Eventually all four black units would be assigned to Fort Davis: the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Led at first by Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, a Civil War hero, the 9th Cavalry had over 50 percent Civil War veterans. The fort contributed to the re-establishment of the nation's military presence throughout west Texas and southern New Mexico, with several posts housing black troopers. Merritt set his soldiers and civilian employees to work rebuilding Fort Davis outside the canyon walls of the first site, using two steam-powered sawmills to cut timber. Soldiers also quarried sandstone from the nearby cliffs, and burned lime for mortar at the post.

Supplying Fort Davis: The Quartermaster Area

A major problem for the original fort, and one that continued during the height of its activity after its reoccupation, was its distance from most of the rest of "civilization". Ensuring that the men at the fort were supplied with what they needed was made much more complicated, not only by the resulting isolation, but also by the aridity and altitude of the area of the Trans-Pecos. While native cultures found in the Davis Mountains game, wood, and water, relying on them to sustain a few hundred people was impossible. This made the role of the Quartermaster that much more important.

|

At left you can see the reconstructed Commissary from the post civil war period; this is, of course, where the Quartermaster would have worked. He would have overseen the bakery, granary, stables and of course the commissary itself. Inside this building, the Park Service has recreated what it probably looked like:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

By the late 1870s the troopers had worked on military road construction, and strung 91 miles of telegraph wire as part of the El Paso-San Antonio communication link. Robert Wooster, in his History of Fort Davis, Texas (1990), noted that many civilians in the area were white CSA sympathizers who saw the Army as a symbol of their defeat, while free black soldiers were reminders of the "lost world" of the Confederacy. Often the stage and mail drivers disliked the black Army escorts, even though the stage company owners preferred to use soldiers rather than pay for their own scouts and guards.

|

As you can see on the aerial view and diagram presented earlier, there are three restored buildings here in the quartermaster area- the Commissary, the Granary (partially restored) and the stables and corrals. We took pictures of most of what we found here in the Quartermaster Area; all of it was immensely interesting.

|

|

I took a couple of panoramic shots here, too, and you can see them below:

|

|

Next, we walked west from the Quartermaster area in the direction of the panoramic shot immediately above.

Post Headquarters

|

As we walked, Fred asked me to pose with the Visitor Center and the Davis Mountains behind me, and you can see his picture here. He also snapped a picture of Karl and I with the ruins of the newest of the barracks behind us.

Near the Post HQ, there was a sign describing many of the Fort buildings and how the Army was supported in various ways. Fred took a picture of us at this sign, and if you would like to read the sign itself, you can do so here.

Prudence and Nancy Near the Post Headquarters I happened to get a shot of Fred taking the picture above |

Mike, Vickie, Ruckman, Nancy, Prudence and Jax As I was taking this picture, Fred got a picture of me doing so. |

The U.S. Army staffed Fort Davis in 1867 with companies of the Ninth Cavalry, composed of black soldiers recruited for the segregated units created after 1866 to permit freed slaves to serve their country in uniform (as they had done in the latter stages of the Civil War). Eventually all four black units would be assigned to Fort Davis: the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Led at first by Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, a Civil War hero, the 9th Cavalry had over 50 percent Civil War veterans. The fort contributed to the re-establishment of the nation's military presence throughout west Texas and southern New Mexico, with several posts housing black troopers. Merritt set his soldiers and civilian employees to work rebuilding Fort Davis outside the canyon walls of the first site, using two steam-powered sawmills to cut timber. Soldiers also quarried sandstone from the nearby cliffs, and burned lime for mortar at the post. Almost all the ruins visible today date from this construction.

|

Mattie Belle Anderson, the town's first schoolteacher, wrote:

| "A non-commissioned officer conducted a school for the children in the post, using the post chapel for his schoolroom five days in the week. Friday nights from 8 to 12 it was used by the officers' families for a dance, the music supplied by the post band which ceased exactly at midnight, leaving lancers or waltz unfinished. That was the band Cinderella would have liked. Every Sunday evening the post Chaplain preached in the chapel, certainly a useful and adaptable ediface(sic)." |

Officer Housing: North Section

|

The road we were walking on went right between these sections, so we first turned north to look at the two-storey houses. A couple of them have ben restored, including the one behind Ruckman in the picture at left. I walked a good ways up that road, and in front of that first restored house, I got a close-up view of it. It seemed like a pretty nice house for the time, although I have no idea how many officer families might have occupied it.

Here are some of the other buildings we found in this part of Officers' Row:

|

|

The Commanding Officer's House |

Ruins of Married Soldier's Housing |

I also did a couple of panoramic views of this area. The first one, done inside the camera, looks west, and you can see 180° from the Commanding Officer's residence at the extreme right and the officer housing along the parade ground at the left:

|

The other view, stitched together from three individual pictures, shows the span of the view to the south from a point near the Commanding Officer's house. That is the back of the chapel in the center of the view:

|

Fort Davis Before the Civil War

|

Now we will be turning west and going around behind Officer's Row. We took quite a few pictures of the back side of this officer housing, but I want to postpone showing those pictures until we return to the southern end of Officer's Row and actually go through one of the houses that has been restored inside. That will put things a bit out of sequence, but it will have the virtue of grouping all the pictures we took of Officer's Row in one place.

So, as you can see from the aerial view, the next area that we will visit is the ruins of the original, pre-Civil War Fort Davis. There has only been a small amount of actual restoration done here. So, at this point, we are to the northwest of the north end of Officer's Row. I stopped before looking at some of the ruins here to take a picture looking southeast at&nbap;Officer's Row.

The competing forces of history and myth that suffuse the story of Fort Davis begin with the construction of the post itself, built in the heady days of the westward surge following the War with Mexico and the "rush" to the California gold fields.

|

If one walked the 460-acre post with a history text in one's hand, one would recognize no less a spectacle than that offered by the beauty of the red cliffs and the green valley of the Limpia. Fort Davis included all the topics that have come in recent years to constitute the "new western" history: issues of race, class, gender, power, and environment. For the past two decades and more the scholarly revision of the westward movement crafted a tale that would challenge prevailing assumptions of the western military and subsequent settlement. Yet the real life of the fort, as chronicled so well by park service historians, would broaden the Fort Davis story.

But the history of those cultures is not what the Fort Davis National Historic Site chronicles, so we can pass over the thousands of years of pre-American cultures in relative silence. What we are interested in here at the Fort is how even a small band of 19th-century military men were kept supplied. In mid-century, there was a surge of travelers through the Southwest to the California gold fields, prompting the national government to conduct Army surveys of the area.

Commissary and Quarter Master Store House (1854-1861) |

To secure these routes against regional Indian tribes, the War Department sent General Persifor Smith to establish the first Fort Davis in 1854. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (for whom the fort and mountains were named) had sought a string of forts along the Rio Grande, but the valley was too barren and forbidding. Smith suggested that six companies of the Eighth Infantry be located in the Limpia Canyon, and 640 acres were leased from a local landowner for the purpose.

Most of the ruins we see here today are pre-dated by that first "fort"; the soldiers in 1854 constructed either tents or modest "jacales" of oak and cottonwood pickers. Four years later, though, the post had permanent barracks built of stone, although most structures still had a temporary look about them- even though Fort Davis was one of the West's largest. Here are some good pictures of the ruins of this first incarnation of Fort Davis:

Enlisted Men's Barracks (1856)/Guard House (1858-1862) This building was used by the CSA for a time. You can see other ruins as well as the two-storey officer's quarters in the background. |

Bakery (1856-1862) We already visited the bakery built when the fort was reoccupied; this is the ruin of the earlier one. |

Both before and after the Civil War, military posts on the frontier and elsewhere found it necessary to grant a "concession" to some local merchant to operate a store on or near the post to supply those items of daily life that were not provided as part of a serviceman's billet. For example, items of amusement, civilian clothing, and other personal items would be sold; for those men who were married, the store would be the main supply point for their families. The role of these merchants, called "sutlers", has been portrayed frequently in movies and TV shows. As at other posts, the efficiency of operations and quantity of merchandise provided by the sutler at Fort Davis influenced greatly life around the military post.

|

But A. W. was just as bad. In 1875, the post adjutant handed A. W. an ultimatum: "Unless you take measures to procure and keep constantly on hand a good stock of marketable goods and conduct the business in a satisfactory manner, measures will be taken to cause your removal." With no improvements, Colonel Andrews, post commander, took action. Chaney's store closed on May 20, and Andrews recommended that Joseph Sender, local agent for the firm of S. Schurtz & Brother, be appointed as sutler. Sender operated a store just off-post, and enjoyed a good reputation among the troops.

Chaney resigned his sutlership, later becoming a county judge. Despite Sender's good reputation, an Ohio Congressman got Belknap to appoint an outsider, John Davis, as the new sutler. Belknap's patronage schemes led to his resignation in 1876, and the new War Secretary, Alfonso Taft, insisted that every post council investigate its trader. Sutler Davis won the support of both the board of officers and commander Andrews, who reported that "no complaints have reached me regarding him, either either in regard to his manner of conducting his business, or the means he employed to obtain his appointment."

|

We found the remains of other early buildings and sites here in this area, including the site occupied by the blacksmith (whose job would have been another critical one).

As the nation moved by 1860 to the brink of civil conflict, the U.S. Army began removing troops from its western outposts to prepare for engagements in the East. That year Lieutenant Colonel Washington Seawell, commander at Fort Davis, asked his superiors to remove his forces to San Antonio, which the Army agreed to do. In 1860 also, voters in Texas were asked if they wished to secede from the Union. Fort Davis residents, linked politically and economically to the national government, decided 48-0 to reject secession. Unfortunately, the Texas electorate, angry not only at the demands of northerners to end slavery, but also at the failure of the Army to stop Indian raiding, decided to leave the Union.

General David Twiggs, commander of the U.S. Military Department of Texas, then surrendered all army posts (including Fort Davis) in February 1861 to the Confederate States of America (CSA), and in April 1861 the Fort Davis troops began their retreat to San Antonio. This brought the first period of the occupation of Fort Davis to an end, although the CSA tried to keep troops here until 1862. Most of the buildings here at the fort fell into disrepair.

Fort Davis Post Hospital (1867-1891)

Fort Davis Post Hospital (Front View/Looking Northwest) |

The story of the post hospital at Fort Davis serves as a basis for interpreting all aspects of military and civilian life at the fort and in the surrounding community. The hospital not only helped to ensure that the soldiers remained healthy, but its operation was critical to the success of all military activities. Its functions were broad and they encompassed more than just treating the sick and wounded.

Fort Davis Post Hospital (Back View/Looking Southeast) |

The construction of a well- provided hospital at any frontier army post was of key importance. While awaiting funds to build a permanent facility at the post- Civil War Fort Davis, civilian workers in 1868 erected a temporary hospital in exchange for medical services. This adobe structure, however, sustained heavy damage during the spring rains of 1870. As a result, Post Surgeon Daniel Weisel began to campaign that a “permanent hospital be erected as early as practicable.”

|

The building of a substantial facility began in the mid- 1870s, with the north ward and central administrative ward completed in 1876. In the summer of 1884 a south ward was added. The hospital consisted of two twelve- bed patient wards connected by a large administrative section. The latter contained the post surgeon’s office, dispensary, kitchen, dining room, hospital steward's room, linen room, isolation ward, and storeroom.

Constructed of adobe on a stone foundation, the hospital was located behind and west of officers’ row. It had a tin roof, wooden flooring, and glass windows with curtains. Wide porches gave it an airy, spacious appearance.

The post hospital at Fort Davis was considered one of the most up- to- date medical facilities west of San Antonio. For example, it had an ether delivery system before such machines were common in the West. Army records for the post show that soldiers suffered predominately from diseases and accidental injuries, not battle wounds. Pension records of former enlisted men reveal that several suffered from blurred vision and/or temporary blindness contracted on campaign in the hot desert sun of the region.

|

Doctors hired by the U. S. Army in the 19th century were some of the best trained physicians in the United States. The army examination for surgeons and assistant surgeons was rigorous and complex. Both surgeons and assistant surgeons were commissioned officers. Acting assistant surgeons (civilian contract physicians) were paid a monthly wage based on the terms of their contracts.

Many surgeons who served at Fort Davis were veterans of the Civil War. William Henry Gardner, post surgeon from 1882 to 1886, entered the War in 1861 as a medical cadet. The following year he was promoted to assistant surgeon. John Vance Lauderdale, who served at Fort Davis from 1888 to 1890, worked on a hospital boat carrying the sick and wounded from battle to medical facilities during the Civil War.

The duties of a post surgeon were numerous and sometimes overwhelming. In addition to treating and caring for the sick and injured, he was responsible for insuring that proper sanitary measures were endorsed and enforced. In this capacity, he was involved in all aspects of garrison life. Among the surgeon’s duties was the regular inspection of living areas, the water supply, and cooking and sanitary facilities. To help ensure that the garrison stayed healthy, he supervised bread baking at the post bakery, oversaw the planting of a hospital garden, and strongly encouraged troops to have vegetable gardens to supplement their rations.

The Surgeon's Office |

The Surgeon's Office |

The surgeon inspected the stables and corrals, functioned as the official coroner, and frequently accompanied troops on campaigns and scouting details. In the late 1880s, when Fort Davis received an ice machine “deemed essential to the comfort and health” of the garrison, the post surgeon had responsibility for its operation. The post surgeon was encouraged to collect and send to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D. C., fauna and flora specimens as well as unusual human skeletal parts. He kept weather statistics and spent hours completing a multitude of reports and forms.

|

We took some more pictures through the windows, and here are some of them:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

The Hospital Staff

Another duty of the surgeon was the supervision of those who assisted him in running the hospital. At his right hand was the hospital steward who was responsible for the day- to- day operation of the hospital. It was essential that the steward have a good medical background since he mixed and administered medications, checked on the condition of patients, and at times was called upon to extract teeth.

Other members of the hospital staff included nurses, cooks and hospital matrons. The nurses and cooks were enlisted men assigned to the hospital from the companies present on post. The matrons, charged with washing the hospital linens, were often wives and /or daughters of the hospital stewards.

Serving the Community

The surgeon and his staff not only served the needs of the military personnel, civilian dependents and employees of the post, but also often cared for the sick of the surrounding area. The journals of Dr. John Lauderdale reveal that he often made house calls on civilians living off the post. At times he was gone for several hours. When called to a neighboring ranch, he sometimes found it necessary to spend the night.

Restoration of the Post Hospital

The exterior of the post hospital at Fort Davis was restored in the late 1960s. Restoration consisted of repairing the adobe walls and putting a new roof and porches on the structure. In the 1980s, a wood walkway was constructed in the administrative section to allow visitor access. In the 1990s, some interior plaster stabilization work was accomplished.

|

Back down from the wide porches, we took quite a few other pictures of the Fort Davis Post Hospital. You might not want to look at all of them, but here are a few of the best:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

Medical treatment at Fort Davis represented state-of-the-art medicine of the nineteenth century. The soldiers at Fort Davis and other frontier posts probably received medical treatment as good or better than what the average American received at the time. Lacking knowledge of what caused disease or infection, army doctors concentrated their efforts on treating symptoms and ensuring proper hygiene and sanitation at the post.

We all thought that the restoration of the post hospital certainly provided us with an understanding and appreciation of a segment of garrison life that is often overlooked. More importantly, it helped to better tell the story of those who lived and sometimes died at Fort Davis during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

As we reached the southwest end of the hospital and turned to leave, there were two more labeled ruins- both from the 1867-1891 period. One was the hospital stewards quarters and the other was the remains of a wood storage building. We had one more set of buildings to see- Officer's Row- and we walked down the long path from the hospital to get there.

Officer's Row (1867-1891)

|

We saw Officer's Row from just about every angle. When we first came around the north end of this row of houses, we saw them from the rear. From that angle, they looked for all the world like small, brick tract homes that were under construction, still waiting for their windows and doors. Here are some of those views:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

I was really impressed by the condition of this row of buildings. They have sat here unoccupied since the fort was decommissioned over 125 years ago; a typical American home today would be a tear-down if it sat unoccupied for five or ten years. I did one of my large panoramas showing Officer's Row from the back:

|

Looking at Officer's Row from the back, you can see some additional foundation ruins; these turned out to be additional enlisted barracks. From the back of these houses, we followed the signs to one of the houses that had been restored inside, and we were able to walk through it. Like the hospital and the commissary, the Park Service has made a good effort to show what the inside of these homes would have looked like:

|

|

We came out the front door of that house to find some benches on the porch where we could sit in the shade and look across the parade ground. I was impressed by the little house; it wasn't much different from the BOQ (Bachelor Officer's Quarters) that I lived in when I was stationed at Fort Lee, New Jersey. Army housing hadn't changed much in 80 years.

|

We sat for a while on the porch, and Fred and I took more pictures of the facades of the houses of Officer's Row. Here are some of them:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

That was pretty much it for our tour around Fort Davis. It was immensely interesting, and we did a lot more and saw a lot more than Fred and I did on our last visit here in the mid-1990s. We walked across the south end of the parade ground back to the Visitor Center and a pit stop. As we did that, I had my camera take a final panoramic shot that takes in the entire Fort:

|

We'd all had a late breakfast, and so we decided to skip a formal lunch and head right to our next stop- a botanical garden about five miles south of the town of Fort Davis.

Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center & Botanical Garden

At the Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute

|

When I proposed the outing yesterday, everyone seemed receptive, so after we were done at Fort Davis we drove back through town so Prudence could leave Jax at their Limpia Hotel room (dogs not being allowed at the Institute) and then out Texas Highway 118 (the road to Alpine) for about four miles to the entrance off to the northeast and the Institute.

We were in three cars, and that turned out to be a good thing, because Ruckman didn't want to hike but just stay at the Visitor Center. Sadly, he wanted to relax with a cigar, but they didn't allow that either- even outside on the verandah. So he took his and Prudence's car and after walking around for a bit while we were out on the trails, headed back to Fort Davis to take up residence at a local pub he and Prudence had dropped in to the night before.

|

Here are Karl, Mike, Vickie and Prudence heading out from the Visitor Center:

|

On the Upper Loop Trail

|

Welcome to the Chihuahuan Desert Region. From low-elevation river valleys to high "sky island" mountain tops, the Chihuahuan Desert contains some unique habitats- moist canyons, gypsum sand dunes, desert wetlands, and playa lakes- that shelter over 3,000 species of plants from cacti to ponderosa pines. It boasts a greater diversity of birds, mammals, reptiles and butterflies than any other ecoregion in the United States or Canada, including butterflies, spiders, scorpions, ants, lizards, and snakes found nowhere else in the world.

The diversity of the Chihuahuan Desert stems from its sheer size- 220,000 square miles. It is one of the largest of the four North American deserts (Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan), and its combination of mountain and basin terrain, ranging from about 1,000 feet at the Rio Grande up to 10,000 feet in some of its isolated mountain ranges.

I made my first movie as we started out (more to record who was in the group so we wouldn't lose anybody), and we also took our first pictures on the trail.

(Mouseover Image Above for Player Controls) |

Heading Out on the Trail |

We passed Stop #2, where we learned a bit about water in the Chihuahuan landscape. The Chihuahuan Desert Region receives only 5 to 15 inches of precipitation per year on average. Water has worn and shaped the mountains and formed the canyons around us. It determines what life this land can support, and creates unique habitats for very specific plants and animals.

|

Animals and plants have adaptations that allow them to live in challenging environments. Some desert animals are able to extract most of the water they need from the foods they eat. Others are nocturnal, or active at night, or spend the day in underground burrows where conditions are moist and cool. This helps them stay cooler and conserve water. Some plants can collect droplets of dew, or alter the type and timing of their respiration.

The Kangaroo rat is perfectly adapted to life in the desert. They are active at night, don't need to drink water (they get all their water from food), and don't sweat or pant.

Although it was warm, walking along the fairly level trail was pretty neat. For the first few hundred feet, we were walking through a meadow, and we reached our third stop just before the trail began to descend and became more rocky.

|

|

The sideoats grama out in front of me can be bundled, dried, and made into brooms and brushes, and the blue grama has seeds that can be ground and mixed with corn meal to make mush. In the distance are rose-fruited juniper with berries to flavor food and wood for fence posts and firewood. Off to the left is an emory oak, whose acorns are a sweet nut about the size of a pine nut when shelled. They can be eaten raw or roasted and ground into flour. Off to the left, out of my picture, were both sotol (leaves for baskets mats, thatch; fiber for ropes; young flower stalks roasted and eaten; dried flower stalks for walking sticks) and agarito (berries eaten fresh, in jellies or as desserts; parts of plant medicinal; parts produce dyes). A cornucopia- if you know where to look.

When we got to Stop #4, we found a posted trail map, and figured out that we needed to continue on the Upper Loop Trail to get over to the Clayton Overlook Trail. The next segment of the trail descended and then ascended again to Stop #20, and so we took it slow. Here are a movie I made and the best of the pictures pictures I took of our group along this portion of the trail:

(Mouseover Image Above for Player Controls) |

Between Stop #4 and Stop #20 |

The Clayton Overlook Trail

|

|

These pictures are in the slideshow at right. To move through the pictures, just use the arrows in the lower corners of each image. the index numbers in the upper left corner of each picture will tell you where you are in the show.

We continued up the north face of the hill, carefully making our way over and around the rocks. Everyone was doing well, and Fred, Mike and I helped where we could. Towards the top of the trail, we reached a point where I thought a congratulatory portrait of the group was in order; that's it below, left. I also made one good movie on the way up that will give you a better idea of how the hike was, and it is below, right.

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Player Controls) |

Here at the vista point, the vistas were, well, pretty incredible:

|

|

Here are a couple of my pictures of the Chihuahuan Desert vista that opened out before us. While we have seen vistas more beautiful than this before, the desert has its own kind of stark beauty.

|

The view from here was really incredible. So I made a movie of what we saw. This allowed me to pan across the area, and also to show you how steep the dropoff was right in front of us.

|

|

The rest of the group decided to wait here while Fred, Vickie, Mike and I went all the way to the Clayton Overlook and geology exhibit on the very top of the hill. Before we left, though, I couldn't resist letting my camera capture the panorama of the Chihuahuan Desert as seen from here:

|

So Fred, Mike, Vickie and I continued on to the top of the hill to find the overlook and geology exhibit. I kind of went cross-country, doing a bit of boulder hopping while the other three more or less followed the trail.

|

We continued on to the exhibit, and when we were done, followed a continuation of the trail. It could have led us onto one of the longer trails that snake around the borders of the Institute's property, but none of us wanted to hike quite that long, so we took a connecting trail to get us back to where we'd left the rest of the group.

The hike to the very top of the hill and the geology exhibit took another fifteen minutes or so- at least it did for me, as I was hopping around on the rocks taking pictures before I approached the Clayton Overlook.

|

|

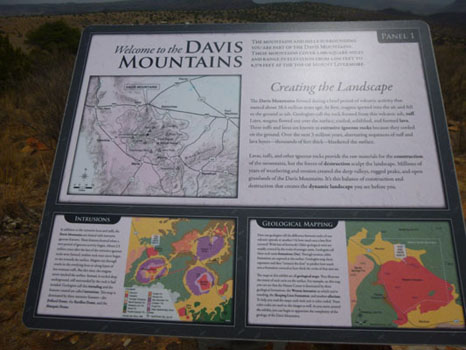

For example, when you were standing and reading the sign describing the geology of the Davis Mountains, shown at left, you would be looking at them in the distance. We all thought that the exhibit was very interesting and very informative, and each of us took the time to look at the views in all directions and read about each one.

I probably should have tried a movie looking 360° from the overlook, but instead I tried to create a panorama instead. It came out pretty well, except that one of th epictures I intended to stitch together didn't turn out, and so I missed about 60° of the view. In any event, here is the panorama I ended up with:

|

(Use Scrollable Window Above to View Panorama) |

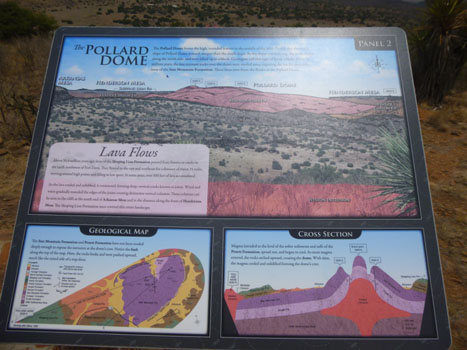

Personally, I thought that the exhibit was immensely interesting, and I thought that if I thought so, then you might, too. But since you couldn't be there to read the signs, I thought that what I might do would be to photograph each of them for you. That was OK, but I found that if I enlarged each one so you could read it, they would be way too big for a normal computer screen. So what I did was to first photograph each sign (a couple got inadvertently cut off a bit) and the view in the direction of each one. Then I took each "section" of each sign and individually enlarged it so it would be readable. (In some cases, I had to retype some of the text when the photo didn't have enough contrast.) Anyway, below you will find each of the ten panels at the exhibit. Each will have a photo of the panel and of the view. To read the panel, just click on any or all of the individual sections, and I'll show you an enlarged, readable view of that section. Close each one when you're done and you can go on to the next. Here are the panels:

Panel 1: Welcome to the Davis Mountains

|

|

Panel 2: The Pollard Dome

|

|

Panel 3: The Barillos Dome

|

|

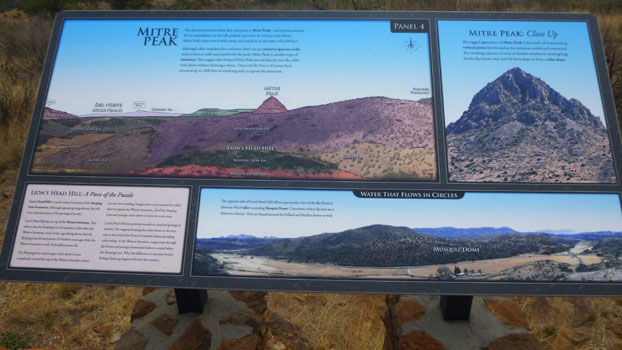

Panel 4: Mitre Peak

|

|

Panel 5: The Musquiz Dome

|

|

Let me interrupt the panels, having come half-way, to show you a panoramic view that I constructed out of the views from these first five stations:

|

Now let's look at the rest of the panels.

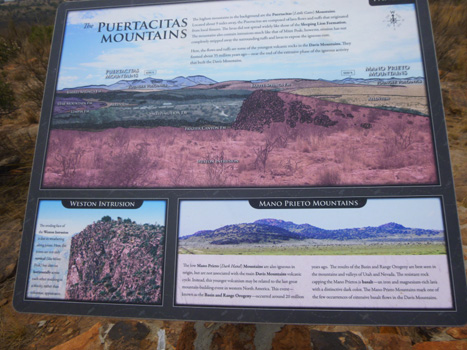

Panel 6: The Puertacitas Mountains

|

|

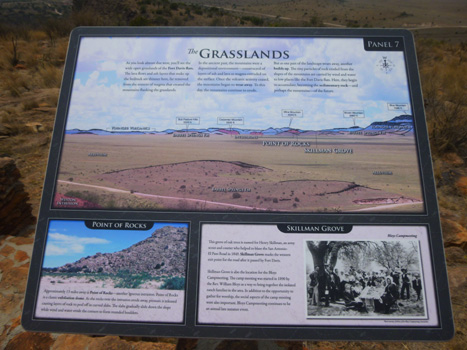

Panel 7: The Grasslands

|

|

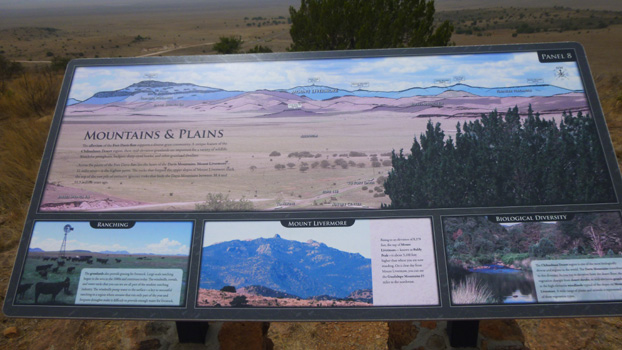

Panel 8: Mountains and Plains

|

|

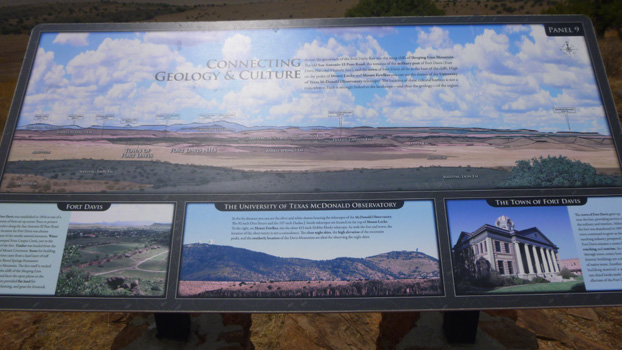

Panel 9: Connecting Geology and Culture

|

|

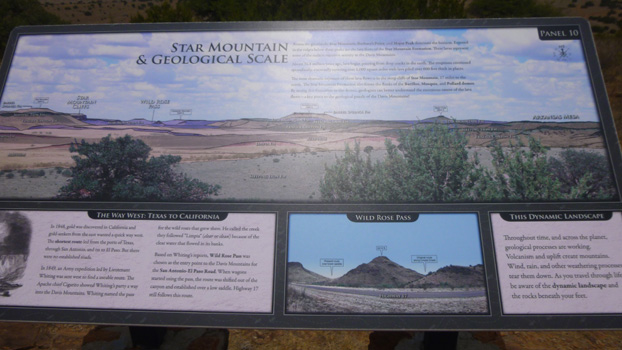

Panel 10: Star Mountain and Geological Scale

|

|

I hope you were able to read most of the signs; as I said, they were pretty interesting.

|

|

When we came around again to the other side of the hill, we didn't see Karl, Prudence and Nancy at the spot where we'd left them, so we called out. That's when we noticed that they'd already descended the trail and were on the flatlands walking towards the Visitor Center. You can make the three of them out in the picture at left.

When we got back down to the trail junction at Stop #20, Mike, Fred and I decided to do the Modesta Canyon Trail; there was supposed to be a waterfall in the canyon and we wanted to see it. So we told Vickie to let the others know that we'd be gone for another hour; she headed off to the Visitor Center and we retraced our steps to Stop #4 to begin that hike.

The Modesta Canyon Trail

|

As I did earlier, I'll describe the things we saw and photographed at the various stops along the way (although we didn't photograph everything.

|

Looking at the walls of the canyon, we could see that the wall on our side looked different that on the other side of the canyon. This was because Modesta Canyon was formed at the contact between to different types of rock. The right wall of the canyon is the edge of a formation named the Weston Intrusion and on our side of the canyon we are walking past the Sleeping Lion Formation, both types of igneous rock (cooled and solidified magma).

The Sleeping Lion rock formed when magma from deep below forced its way through the rock layers above it and flowed out over the surface of the Earth, cooling and crystalizing to form solid rock, called extrusive igneous rock. The Weston rock formed after the Sleeping Lion, from magma that forced its way up from a different deep source but never made it all the way to the Earth's surface, stopping at the Sleeping Lion level. This magma cooled, crystallized and again formed solid rock, called intrusive igneous rock.

Erosion of the layers above and around the upper part of the Weston exposed the contact between the Weston and Sleeping Lion, and has been the focal point for continued erosion that, over time, has dug down forming Modesta Canyon.

Here is a picture of the trail we are on, and also a movie I made as we were walking down it:

The Modesta Canyon Trail |

Walking the Trail (Mouseover Image Above for Player Controls) |

Going down the trail was pretty easy, although as we descended, I realized that sooner or later we'd have to climb back out, but at least the trail would be different.

Fred on the Trail |

|

Fred on the Trail |

Looking Up the Watercourse |

|

A Texas Madrone |

It only took us about twenty minutes to make our way down to the bottom of the canyon where, as advertised, we found the Modesta spring. All of a sudden we had abundant green vegetation, due to the water that is almost always present.

|

This was the first water we'd seen along the trail, and also the first ferns. We also had a surprise visitor along the trail, as you will see if you look at the first of the few pictures we took down here:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

Modesta Spring is typical; rainwater soaks through the soil and collects in layers of porous rock and sediment underground- an aquifer. Erosion cuts through the aquifer, allowing water to flow out and collect in low areas as pools. Rainfall helps to recharge the aquifer. But even with normal rainfall, flow rates can diminish or even stop if the amount of water being pumped out of an aquifer exceeds the amount being added.

|

Here are some views of the Sleeping Lion Formation:

(Click Thumbnails to View) |

I put together a panorama of the formation, and you can use the scrollable window below to pan across it:

Once we had climbed out of the canyon, and were up on the Weston Intrusion, the walking was fairly level, although we were gently still ascending to the level of Stop #20. Near the end of the trail we went into a maze of upright standing blocks of rock. These were rocks of the Weston Intrusion that were formed when the molten rock cooled below ground. As this cooling occurred, the rocks contracted and formed two sets of parallel fractures at right angles to each other. Erosion wore away the soil, and eventually the vertical fracture was revealed as these rock pillars. Below, left, is a photo of the pillars, and below, right, is a slideshow of the best of the pictures we took between the canyon and our return to Stop #4. As usual, use the little forward and backward symbols to move through the slideshow pictures:

|

When we got back to Stop #20, we took the short trail back to the Visitor Center. There we found that Ruckman had gone back to Fort Davis to hang out at one of the local pubs. Everyone else was still here, and the group (minus me) went off to look at the small botanical garden adjacent to the Visitor Center. Fred brought back only a couple of pictures- one of Nancy, Jax, and Prudence and another that he took with his closeup lens of a bumble bee doing what bumble bees do; you can have a look at that latter picture here.

Dinner at the Limpia and a Walk Around Fort Davis

The Limpia Hotel

|

A third building contained the restaurant. I wasn't quite sure if the restaurant was actually part of the hotel or a separate business; it was located across an outdoor courtyard from the main hotel building. The three buildings formed a little compound, although you didn't have to go through any of the buildings to get to the courtyard.

The Bistro was very nice, and the dinner was quite good. I should have engaged the services of one of the waitstaff so I could have gotten in the picture as well, but here is our group at dinner on the last night of our little vacation.

The Town of Fort Davis

|

After a really nice dinner, we thanked Ron and Prudence for all their planning and for including us on their trip. Since they were staying at the Limpia, we said goodbye to them and the headed back to the Indian Lodge. There, we thanked Nancy and Karl and said goodbye to them as well, and to Mike and Vickie, for we would be leaving early in the morning for our trip back to Dallas.

Since we were coming back from West Texas, Fred took the opportunity to stop to visit his Mom, so as he did once before, he dropped me at the Comanche Best Western where I stayed the night while he was at his Mom's. He picked me up the next day, and we drove back to Dallas with two little gifts he had picked up at his Mom's. If you want to know what they were, just check this year's "Pets" page under the date "May 14".

Our thanks to Prudence, Nancy, Ron and Karl for all they did for us on this trip to Big Bend.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

May 11, 2016: Big Bend- Santa Elena Canyon |

|

Return to the Big Bend Trip Index |