|

May 29, 2017: Prague Castle and Petrin Hill |

|

May 27, 2017: Karlstein Castle; Troja Palace; Prague Botanical Garden |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |

It's Sunday, and Jeffie will be spending the day with us again. First, we'll take another trip outside the city to see the Sedlec Ossuary (the Bone Church) in the town of Sedlec, a suburb of Kutná Hora about 40 miles east of Prague. We'll return to Prague shortly after noontime, and then spend the rest of the day walking with Jeffie around the city, seeing some of the lesser-known things that she knows about.

The Sedlec Ossuary/

The Cemetery Church of All Saints

Getting to Kutna Hora

|

The town itself was founded in 1142 with the settlement of Sedlec Abbey, the first Cistercian monastery in Bohemia. By 1260 German miners were mining silver in the mountain region, which they named Kuttenberg, and which was part of the monastery property. Silver had been discovered in the area in the 10th century, and by the 1200s, Bohemia (and Kutna Hora) was a trading crossroads.

From the 13th to 16th centuries the city competed with Prague economically, culturally and politically. Although Prague eclipsed Kutna Hora and all other Bohemian towns by 1300, there were so many cultural locations in that smaller city that in 1995 the city center was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1300 King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia issued a new royal mining code; Kutna Hora developed quickly, pidity, and at the outbreak of the Hussite Wars in 1419 was the second most important city in Bohemia- and a favorite residence of several Bohemian kings.

|

Our Walk Into Sedlec

|

Save for the signage, Sedlec looked like a small Texas town- quiet streets and small houses. We snapped a few pictures of street scenes along our walk (which took us by a Philip Morris cigarette building), and you can look at them below.

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Kutná Hora was burned in 1422 during the Hussite Wars, but under Bohemian auspices it awoke to a new period of prosperity. Along with the rest of Bohemia, Kutná Hora passed to the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria in 1526. In 1546 the richest mine was hopelessly flooded; this began a 200-year decline of the city. In the insurrection of Bohemia against Ferdinand I the city lost all its privileges; it was devastated by the plague; the Thirty Years' War left it in ruins. After the peace, attempts were made to re-open the mines, but these failed, the town became impoverished, and in 1770 was devastated by fire.

|

Kutná Hora and the neighboring town of Sedlec are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Among the most important buildings in Kutná Hora are the Gothic, five-naved St. Barbara's Church, begun in 1388; the Italian Court, formerly a royal residence and mint, which was built at the end of the 13th century; the Gothic Stone Haus, which since 1902 has served as a museum and contains one of the richest archives in the country; and the Gothic St. James's Church, with its 280-foot tower. In Sedlec itself are the Gothic Cathedral of Our Lady and the famous Ossuary.

After a ten-minute walk from the station, we turned north at the Church of Our Lady, heading towards the Ossuary. The Ossuary is a popular tourist destination, and the shops and stores in town take advantage of the theme- as you can see at right. Just a few blocks up the street from the Cathedral we came to The Bone Church itself.

The Sedlec Ossuary (The Bone Church)

|

Before we enter the Ossuary, a bit of history. In 1278, Henry, the abbot of the Cistercian monastery in Sedlec, was sent to the Holy Land by King Otakar II of Bohemia. He returned with him a small amount of earth he had removed from Golgotha and sprinkled it over the abbey cemetery. The word of this pious act soon spread and the cemetery in Sedlec became a desirable burial site throughout Central Europe.

During the Black Death in the 14th century, and after the Hussite Wars in the , many thousands were buried in the abbey cemetery, so it had to be greatly enlarged. Around 1400, a Gothic church was built in the center of the cemetery with a vaulted upper level and a lower chapel to be used as an ossuary for the mass graves unearthed during construction, or simply slated for demolition to make room for new burials.

The Chandelier |

The Coat of Arms |

In 1870, František Rint, a woodcarver, was employed by the Schwarzenberg family to put the bone heaps into order. The bones he used were disinfected and bleached with chlorinated lime and placed in original patterns- including a chandelier in the middle of the chapel and a coat of arms of the Schwarzenbergs. He even used some of the bones to create his signature; it is located at the bottom of the staircase coming down from the entrance.

Pictures we took of the bone chandelier and the Schwarzenberg coat of arms are at right.

It goes without saying that the Ossuary was one of the oddest places we have ever visited. It seemed as if everything- save for the stone walls themselves- were constructed (artistically) out of bones. And even the walls were largely hidden by the bone decorations on them. It was simply amazing.

|

|

There is a slideshow at left for 25 of the many pictures we took. You can move backward and forward through the slides by clicking on the little arrows in the lower corners of each slide. In the upper left corner of each slide there is a tracking number, so you can tell where you are in the show.

Enjoy looking at as many of the pictures as you wish!

|

Inside the Cemetery Church of All Saints

|

|

We spent a bit of time wandering around the small church; out in the room in front of the nave was where you could look down into the ossuary, and there were a number of exhibits there as well. Some of them repeated information about the ossuary below, but others were more descriptive of the church. I've put some of the information from these exhibits in the pictures and scrollable windows below so you can have a look:

|

Outside the Cemetery Church of All Saints

|

Officially called the Cemetery Church of All Saints with Ossuary, this small country church really is a fascinating place. The Ossuary, which is what most people come to see, is located in an underground chapel of the church; the church and Ossuary were originally part of the Sedlec monastery. The church was built in the 14th century, and according to legend, one of the local abbots brought soil from Jerusalem and scattered it around the cemetery making it the oldest so-called “holy field” in Central Europe.

As we walked around the north side of the actual church building, we could see that two projects were underway. One was intended to ensure that the church itself remain stable, and there was much reinforcing going on. The excavations necessary to do that were revealing yet more buried bones, and these were being tagged and slowly removed from the earthen matrix.

|

The other element of the excavations on this side of the church was the uncovering of yet more bones. It was unclear to us whether the effort to excavate the bones was the cause of the stabilization work going on, or whether the stabilization work was simply providing access to more of the buried bones.

|

|

As we walked by the excavations, we didn't see anyone actually at work (this being Sunday), but Fred got what I thought was an interesting picture of someone's work area. We weren't at all sure who's picture that was or why it was there.

As for the cemetery, it was fairly small, but the markers and plots were squeezed tightly together.

|

|

In the middle picture below, if you will click on the inscription on the headstone that is prominently featured, I will pop up a window with Fred's closeup of that inscription:

|

|

|

Walking around the church and through the traditional cemetery seemed oddly comforting as compared to the existential use of the bones of so many thousands to construct and decorate the ossuary underneath the church.

|

|

Our circumnavigation of the church complete, we were back out near the entrance gate, and from here we could get very good views of the Cemetery Church of All Saints. Here are the best two of the many pictures of the church we took:

|

Outside the gate to the church grounds, we paused to take a look at the beautiful monument or sculpture that was adorned with many religious figures. I've tried to find out more about it, as there was no plaque on it or nearby, but I have been unable to find specific mention of it. It was a good backdrop for the last couple of pictures we took here at the church:

|

|

The Sedlec Cathedral/

The Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady and St. John the Baptist

A couple of block south of the Cemetery Church is the Cathedral of the Assumption- the oldest Cistercian cathedral in Bohemia; the cathedral dates to the middle of the 12th century, the time of the largest expansion of the Cistercian Order.

The Walk to the Cathedral

|

|

And here are a couple of street scenes as we walked south the few blocks to the cathedral:

|

|

Outside the Cathedral of Our Lady

|

The area's first community of monks came from the Waldsassen monastery in Bavaria. In contrast to the then tradition of linking the establishment of the monastery with the colonization of the adjacent territory, the Sedlec monastery was established in a heavily populated area. The founder’s settlement was established in the center with several smaller churches around whose brickwork is preserved today as part of the baroque convent. Ownership of the monastery was made up of a tenement of villages and farmsteads from the immediate and wider surroundings.

With the exception of the names of the abbots, no records of the first one hundred and fifty years of the existence of the Sedlec community remain. Sometime around then the first convent was built, whose foundations were discovered under the paving of today’s cathedral building.

|

The Sedlec monastery took a deep breath after the Thirty Years War when it slowly managed to consolidate economic conditions, stabilize the number of monks and strengthen religious discipline. The abbots began extensive restoration activity at the derelict monastery as their financial position allowed; this continued to 1685 and the election of Jindrich Snopek as the abbot (1685–1709).

Snopek was born in 1651 and joined the Cistercian Order at the age of twenty; he was thirty-five when he was chosen Abbot. He is linked in particular to the monastery’s extensive restoration work on the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, which brought it to its current state. Poor trade and extensive building and the related artistic activity, which encompassed the construction of the convent, undermined the economic self-sufficiency of the monastery, however.

As a result of the Josephine reforms the monastery was abandoned in 1783, the cathedral was deconsecrated and closed, and the mobiliary art was nearly completely all auctioned off. In 1806 the cathedral assumed the function of a parish church for Sedlec and nearby Malín, a function it fulfills to the present day. In 1812 a tobacco factory was established in the monastery building, the early forerunner of the large Philip Morris complex that is adjacent to the cathedral to the northeast. The villages and farmsteads that formed the dominion of the Sedlec monastery were purchased in 1819 by the Prince of Schwarzenberg, and the patronage of that family kept the church functioning.

After extensive reconstruction, which was financed in part from in-house resources and in part by the architectual preservation program of the Czech Republic Ministry of Culture, the cathedral was reopened to the public in the spring of 2009.

|

|

The Inside of the Cathedral of Our Lady

|

Santini wove it into the building design unique cantilever construction elements, the so-called "Bohemian flat valut"- forming a side nave ceiling and a spiral staircase with no center pillar.

There were three paintings on prominent display off to the side of the nave.

The Foundation of the Monastery The Foundation of the Monastery |

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary The Assumption of the Virgin Mary |

The Destruction of the Monastery The Destruction of the Monastery |

The third painting was graphic; at the time the monastery was destroyed in 1421, a great many monks were killed.

|

I might have liked to explore the entire church, but I was cognizant that Jeffie and Fred were waiting for me outside, so I settled on a visit to the Treasury Room.

|

The dominant item on display in the Cathedral Treasury Room is the original gothic Monstrance of Sedlec from the 14th century. It is a liturgical item used for storage of the altar-bread in the secret of Eucharist.

The Monstrance of Sedlec is one of the only ten extant gothic monstrances and by the recent research it is the oldest gothic monstrance in the World.

This monstrance is thought to be the work of Petr Parlér, the court designer of the Emperor Carl IV and also the designer of much of the ornamentation in both the Cathedral of Saint Vitus in Prague and the Church of Santa Barbara in Kutná Hora.

The Monstrance of Sedlec was probably not made exactly for the Sedlec Abbey, however, but it was given to the Abbey by a group known as the Brotherhood of Christ´s Body in Kutná Hora.

This jewel is made from gilded enchased silver. The height of monstrance is three feet and it weighs about 12 pounds. It was certainly beautiful, softly-lit and simply-displayed.

I spent about twenty minutes in the church, and then returned outside to rejoin Fred and Jeffie for our walk back to the train station and our return trip to Prague.

The Return Trip to Prague

|

We had noticed when we arrived that, as we have seen elsewhere, the tunnel walls were decorated- apparently by local artists, as each time we've seen these decorations they've been different. They were quite intricate here, and there are some pictures below if you want to have a look:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

When we boarded the train, we found it was very crowded, and so we weren't able to find any seats together. Since the ride wasn't very long, we three just decided to stand in the corridor alongside the compartments and watch the scenery out the open windows. That's where Fred got this picture of Jeffie and I. We stood at the windows the whole way back, just watching the scenery go by. Here are a couple of typical views of the countryside:

|

|

I like trains, but don't ride them very frequently (although if I lived in Europe, I certainly would). I made a couple of movies as we went along. They aren't all that interesting I guess, but I'm going to include them here. Obviously, most of the audio was wind noise, so I have just removed the audio track altogether.

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

We arrived back at the Prague main station a little hungry and thirsty, so while Jeffie went in one shop for a vegetarian entree, Fred and I popped into Burger King for a sandwich and fries. If you are curious, the prices work out to be essentially the same here as in the States, although perhaps just a bit more expensive. Everything is in Czech crowns; each is worth about 4 cents. To translate prices, I just divide by 25. (Jeffie thinks it is easier to multiply by 4 and divide by 100, but you can take your pick. Either way, large fries for 35 crowns makes them about $1.50.)

Wenceslas Square (Prague)

We arrived back in Prague about two in the afternoon, and took our food out to the lawn in front of the train station to eat; the little park in front of the station is a popular spot, and there were lots of other folks having impromptu picnics as well. For our first activity back in Prague, Jeffie wanted us to see Wenceslas Square.

|

The walk over to the square from the station only took ten minutes, and there were lots of neat buildings and other interesting things to look at along the way. Prague is very much a walking city; that's really the only way to see everything. This might be Sunday, but at least the window washers were at work:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

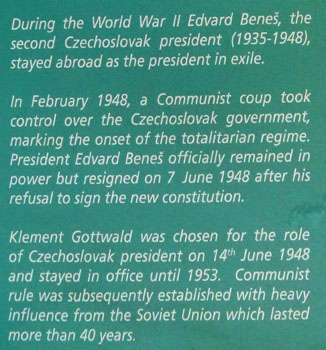

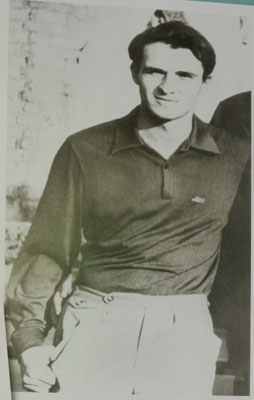

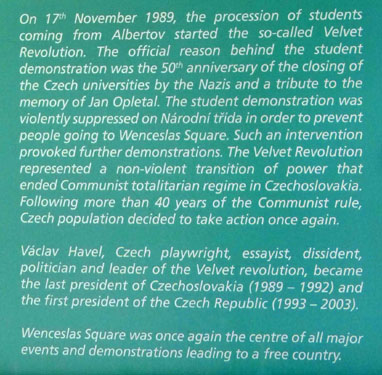

As we were walking along, we went by a construction site, blocked from view with the usual plywood wall. Instead of viewports, though, there was a little mini-exhibit having to do with The Velvet Revolution. This was the non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from November 17 to December 29, 1989. The sequence of events is well-known to Czechs, but not so much to Americans, but it all began, as it often does, with students, who seem oftimes to be without fear. On November 17, 1989, there was a demonstration by a hundred or so students, suppressed, as usual, by riot police. But this time, three days later, a half million people had taken to the streets- most of them in Wenceslas Square. A two-hour general strike involving all citizens of Czechoslovakia occurred on November 27; this resulted in the mass resignation of the entire top leadership of the Communist Party, including General Secretary Miloš Jakeš.

The next day, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced that it would relinquish power and dismantle the one-party state, and the legislature promptly deleted the sections of the Constitution giving the Communists a monopoly of power. The borders with West Germany and Austria opened in early December. On December 10, President Gustáv Husák appointed the first largely non-communist government in Czechoslovakia since 1948, and then resigned. Alexander Dubcek was elected speaker of the federal parliament on December 28 and Václav Havel the President of Czechoslovakia on December 29, 1989. In June 1990, Czechoslovakia held its first democratic elections since 1946, and the revolution was over.

The exhibit we passed consisted of pictures from the time and short explanations. Here is most of what we saw posted:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From the station, our route brought us into Wenceslas Square, about in the middle (measured from southeast to northwest). Wenceslas Square is one of the main city squares in Prague; it is the center of the business and cultural communities in the New Town. Many historical events have occurred here (including the demonstrations of the Velvet Revolution), and it is a traditional setting for demonstrations, celebrations, and other public gatherings. The square is named after Saint Wenceslas, the patron saint of Bohemia. It was formerly known as Horse Market, for its periodic accommodation of horse markets during the Middle Ages; it became Wenceslas Square in 1848. From the middle of the square, here's our first two pictures:

Looking Southeast |

Looking Northwest |

Less a square than a boulevard, Wenceslas Square has the shape of a very long (a little less than half a mile) rectangle (about nine acres in size) oriented in a northwest–southeast direction. The street slopes upward to the southeast side. At that end, the street is dominated by the grand neoclassical Czech National Museum. The northwest end runs up against the border between the New Town and the Old Town. The two obvious landmarks of Wenceslas Square are at the southeast, uphill end: the 1885–1891 National Museum Building, designed by Czech architect Josef Schulz, and the statue of Wenceslas. We went to that end of the square first, to have a look at the statue of St. Wenceslas.

|

|

The mounted saint was sculpted by Josef Václav Myslbek in 1887–1924, and the image of Wenceslas is accompanied by other Czech patron saints carved into the ornate statue base: Saint Ludmila, Saint Agnes of Bohemia, Saint Prokop, and Saint Adalbert of Prague. The statue base, designed by architect Alois Dryák, includes the inscription "Saint Wenceslas, duke of the Czech land, prince of ours, do not let perish us nor our descendants".

|

As for the history of the square, that begins in 1348, when Bohemian King Charles IV founded the New Town of Prague. The plan included several open areas for markets, of which the second largest was the Horse Market; at the southeastern end of the market was the Horse Gate, one of the gates in the walls of the New Town.

During the Czech national revival movement in the 19th century, a more noble name for the street was requested. It was at this time that the statue of St. Wenceslas was installed, and so the square was renamed in the Saint's honor. In 1918, Alois Jirásek read the proclamation of independence of Czechoslovakia in front of the Saint Wenceslas statue.

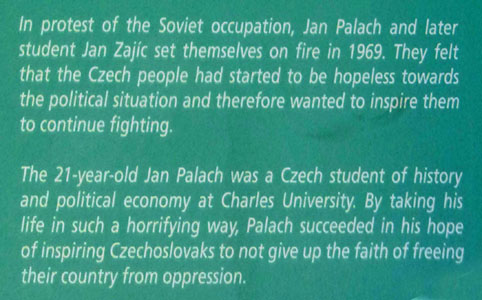

The Nazis used the street for mass demonstrations, and during the Prague Uprising in 1945, a few buildings near the National Museum were destroyed. On 16 January 1969, student Jan Palach set himself on fire in Wenceslas Square to protest the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union the year before.

On 28 March 1969, the Czechoslovakian national ice hockey team defeated the USSR team for the second time in that year's Ice Hockey World Championships. As the country was still under Soviet occupation, the victory induced great celebrations. Perhaps 150,000 people gathered on Wenceslas Square, and skirmishes with police developed. A group of agents provocateurs provoked an attack on the Prague office of the Soviet airline Aeroflot, located on the street. The vandalism served as a pretext for reprisals and the period of so-called normalization.

The square's largest gathering would occur in 1989, during the Velvet Revolution, when upwards of 400,000 people gathered in support of throwing off the Communist yoke- a movement that succeeded in less than six weeks.

Wenceslas Square is lined by hotels, sidewalk cafes, offices, retail stores, restaurants, currency exchanges, and fast-food franchises. To the dismay of locals and city officials, the street is also a popular location for prostitutes to ply their trade late at night. Many strip clubs exist on and around Wenceslas Square, making Prague a popular location for stag parties.

Fred had me stand just southeast of the St. Wenceslas Statue so he could get this nice view of Wenceslas Square. Then I went to the other end of the statue so I could make this panoramic view of Wenceslas Square, looking northwest:

At the southeast (top) end of the square are the Czech National Museum as well as the former Communist parliament building (which is now used for various exhibits and shows that revolve around Czech culture.

|

|

Before we left the top of the square, Fred got a good closeup picture of one of the ornamental sculptures on the Czech National Museum. From the top of the square we walked northwest along the west side of the square, looking for the building Jeffie wanted to take us inside so we could see a parody of the St. Wenceslas Statue created by David Cerný. On the way, we passed many handsome and interesting buildings (you can see a couple of them here and here). Fred also found and photographed an interesting frieze on one of the buildings we passed.

After a bit of searching, we finally found the Art Nouveau building called the Lucerna Palace, and went inside to its open gallery (now lined with shops and stores like an indoor mall).

|

This sculpture is a mocking reference to the more famous equestrian statue of King Wenceslas that sits in Wenceslas Square, and possibly a mocking nod to Czech president Vaclav Kraus, although the artist will not say what his intentions actually were.

I thought the inside of the building was architecturally very interesting, and so I took a single picture of the beautiful, intricate stairs at one end of the gallery. Apparently, there was some kind of coordinated dance competition or exhibition going on; we saw five or six groups of similarly-dressed kids, each doing some sort of coordinated dance-like movements.

We left the Lucerna and walked back out to Wenceslas Square where Jeffie said we really should see the black babies at the television tower (and go up in it as well). So that's where we headed next.

The Prague TV Tower

Our next destination, which will involve walking through some new areas of Prague, is the Soviet-era transmission tower, which now is the main TV transmission tower for Prague. It has observation decks we can visit, and is the site of another of David Cerný's surrealist art installations.

Jirího z Podebrad Square

|

When we came up aboveground, we found ourselves in the southwest corner of a park, and the first thing we saw was a really interesting fountain- big enough that bunches of folks could sit up on it and enjoy it.

|

Jirího z Podebrad Square was established in 1896 and was previously called King George Square (Námestí krále Jirího). Its name was changed to the current one in 1948. The majority of the square is a city park, built in the 19th and 20th centuries on the site where there were originally gardens. The square is dominated by the exceptional Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord (Kostel Nejsvetejsího Srdce Páne).

The Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord is a Roman Catholic church here in the Vinohrady district. It was built between 1929 and 1932 and designed by the Slovene architect Joze Plecnik.

|

The church is considered one of the most significant Czech religious constructions of the 20th century. In the wide, 130-foot-high tower wall is a huge, 25-foot-diameter glazed clock (the largest in the Czech Republic).

In the basement is a spacious chapel with a barrel vault. Inside is an altar made of white marble, a 10-foot gilded figure of Christ, and six statues of the patrons of Bohemia.

During WWII, the six bells from the tower were melted down for arms production, and in 1992 two copies were returned. Since 2010, the church has been listed as a National Cultural Monument in the Czech Republic.

|

|

From a point on our route just past the front of the church, I stopped to let my little camera make a panoramic view of the square; the view looks back to the southwest:

|

We could have found the TV Tower easily from the time we came up out of the Metro Station, because it is so tall that you can always see it in the distance. Leaving the square, we were back walking along neighborhood street, where Fred found some interesting and quirky things to take pictures of:

|

I wasn't with Fred when he took the picture below, so I don't have any context for the cats seemingly hanging on a clothesline:

|

The Zizkov Television Tower

|

The tower stands 709 feet high; the observatory is at 300 feet, while the hotel room and cafe are slightly lower. The tower has a capacity of 180 people. There were three elevators serving all the pods, and it took us about fifteen or twenty seconds to get up to the observation level.

Three of the pods, positioned directly beneath the decks at the top of the tower, are used for equipment related to the tower's primary function and are inaccessible to the public. The remaining six pods are open to visitors, providing a panoramic view of Prague and the surrounding area. The lower three house a recently refurbished restaurant and café bar.

The tower cost $19 million to build; it weighs 11,800 tons and is also used as a meteorological observatory. It is a member of the World Federation of Great Towers.

When we got to the tower, we found that the actual entrance was below grade, so we went down the steps and into the lobby. I checked with the young ladies at the ticket/information desk whether seniors got a discount; they didn't, so I got three tickets for us to go up to the observation level.

When we came out of the elevator into the observation level pods, we could see immediately that the views would be impressive, and as soon as we got near the windows in the first of the three pods we visited, we could see that we would be treated not only to impressive, to-the-horizon vistas but also to closeup-views of Prague from above. Of course, we needed to begin with shots of each other backdropped by the vistas to the horizon:

|

|

We spent the next hour or so wandering through all three pods, sticking close to the windows to admire one spectacular view after another. We of course took a lot of duplicate pictures, which has enabled me to pick from two choices for just about every view for inclusion here.

|

|

I want also to include some pictures taken in the central area between the pods. I particularly enjoyed learning about the one-room hotel that is here in the tower.

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

As it turned out, not all the attractions of the tower could be seen from the inside, or from the pods high up. One of the most interesting aspects of the tower can only be seen from the outside, and even then, a telephoto lens or binoculars are de rigeur.

|

|

In 2000, ten fiberglass sculptures by Czech artist David Cerný called "Miminka" (Babies) were temporarily attached to the tower's pillars; they were positioned crawling up and down. The sculptures were admired by many and were returned in 2001 as a permanent installation. Another three babies, made from bronze, can be found in Prague’s Kampa Park.

Like many examples of communist-era architecture in Central and Eastern Europe, the TV tower used to be generally resented by the local inhabitants. It also received a spate of nicknames, mostly alluding to its rocket-like shape, e.g. "Baikonur" after the Soviet cosmodrome or some more political, like "Jakes's finger", after the Secretary General of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. In 2009, the Australian website Virtualtourist.com called the Zizkov TV Tower the second ugliest building in the world (behind the Morris A. Mechanic Theatre in Baltimore).

Although official criticism during the time of its construction was impossible, unofficially the tower was lambasted for its 'megalomania', its 'jarring' effect on the Prague skyline, and for destroying part of a centuries-old Jewish cemetery situated at the tower's foundations. However, the official line remains that the cemetery was moved some time before the tower was conceived. Recently, the tower's reputation among Czechs has improved, and today it attracts visitors focusing on the tower's technological innovations and great views over the city skyline.

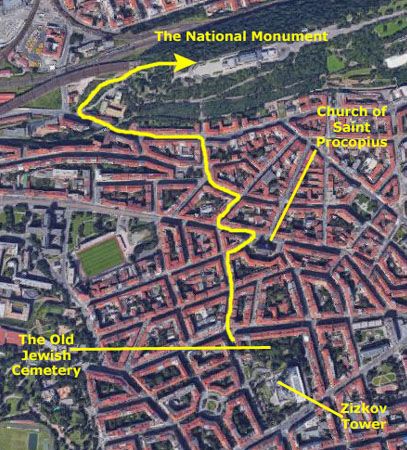

We enjoyed our visit to the tower, and the views were certainly worth it. We were intrigued by the story about the Jewish cemetery that might have been partially destroyed, so we thought we would go see what was left of it.

The Old Jewish Cemetery

|

After WW II, the cemetery was hardly maintained at all; it became unkempt and started to deteriorate and gradually grow over. Also a great number of tombstones were destroyed. The cemetery was effectively closed in the 1960s, and the area around it turned into a park- Mahlerovy sady. However, the oldest part of the cemetery remained preserved and it was then separated from the park by a wall. In this part tombstones with the noted Jewish personalities are situated.

In the second half of the 1980s the television tower was built in the park territory. The tower offers its visitors not only the view of the whole cemetery but also the view of the whole city.

The so far undamaged part of the cemetery in Fibichova street is listed as an historic site in Prague, and in 1999 it was placed under the protective wings of Židovské muzeum of Prague (Jewish Museum of Prague). The original cemetery fountain building with a memorial plaque from 1792 has also survived and so a number of interesting tombstones. Extensive construction modifications and reconstructions of the burial ground were carried out due to which the cemetery has been open to the public since September 2001.

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

The National Monument in Vitkov

For our next stop, Jeffie's chosen the National Monument, located on top of a high hill perhaps a mile north of the Old Jewish Cemetery. It has a statue she thinks we should see, and another tower we might go up in.

The Neighborhood of Žižkov

|

|

The pictures we took while we walked along were eclectic. Fred liked the doorway shown at left and the sculptures above it. Passing a school, we found this interesting wall mural:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Žižkov was historically a working-class district, and was sometimes referred to as "Red Žižkov", because so many of its inhabitants supported left-wing parties. Before World War II, it had a reputation as a rough area. This reputation spread across the whole former Czechoslovakia and it was still possible to trace it amongst the people many decades later. The Žižkovians were very proud of their bad reputation and up to this day they tend to refer to their neighborhood as the "The free republic of Žižkov". This sentiment was very often a source of inspiration for novelists or film makers. This feeling showed up in the humorous novel "Secrets of the Žižkov Underground", as well as other publications and films.

|

By the 1880s, Žižkov had become a large town with 21,212 inhabitants. The first mayor of Žižkov was Charles Hartig, who is credited with the naming of streets, squares and houses after famous Czechs from Jan Hus to Komensky. On 15 May 1881, Emperor Franz Josef I promoted Žižkov to the status of a city. By 1920 almost the whole district was developed; and it became one of the first neighborhoods outside of the historic city center to be connected to the tram system. The independent city of Žižkov was eventually incorporated into Prague in January 1922.

In the early 20th century, Žižkov developed into the "Bohemian" part of Prague, with many artists living or performing there. It was a writers community, too, one of the reasons why, at the end of World War I, they originated the concept of the Žižkov Free Republic resistance movement; this led to Žižkov's being a hotbed of the Czech resistance movement. The families that hid the operatives of Operation Anthropoid. After the Velvet Revolution, often in connection with the restitution of houses, reconstruction and rehabilitation began in Žižkov. While many houses have since been renovated, the look of the neighborhood has not changed much.

|

|

The Church of St. Procopius

|

Žižkov became an independent city in 1881, but an association for the establishment of a Catholic church was formed in 1879. In 1883, it bought a building with a large dance hall, which was converted into a simply-decorated chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This chapel accommodated thousands of the faithful for more than 20 years, even after the dedication of St. Procopius Church, closing only in 1919.

In 1898, the foundation stone for St. Procopius Church was ceremonially laid by the Archbishop of Prague, Cardinal František Schönborn, on the 50th anniversary of the reign of Franz Joseph I of Austria. Construction of the "Jubilee Church" took five years. The church was consecrated in 1903, and the first parish priest was Mons. Eduard Šittler. Between 1992 and 1997, the church was thoroughly restored, with the support of the district administration.

The church is 150 feet long and 55 feet wide, and accommodates 2000 people. The height of the dome is 50 feet; the tower reaches a height of 220 feet. The church has two entrances, on the northern and western sides. Over the west entrance is a relief of St. Adalbert, created by Josef Pekárek.

|

|

The main altar is Neo-Gothic, designed by architect František Mikš. In the center is a statue by the sculptor Štepán Zálešák of St. Procopius, the patron saint of the church, surrounded by Saints Cyril and Methodius. Eight panel paintings by Karel Ludvik Klusácek present scenes from the life of St. Procopius. The top of the altar is decorated with a group of the Crucifixion of Our Lord.

A side altar has a statuette of Madonna with Jesus, possibly the original from the first half of the 15th century. It was saved during the Thirty Years' War in the house called At the Three Acorns in the New Town of Prague, where it was held until 1742. The chapel of Our Lady, on the right side, has a panel with scenes from her life. The chapel of the Divine Heart of Our Lord, on the left, has images of St. Augustine and St. Alois. These were also made by Zálešák.

The Baroque Venice chandelier was donated to the church by the Prince of Auersperg. The pulpit with granite stairs was made according to the design of Mikš. The organ was made by the Žižkov company of Emanuel Peter. The stained glass windows were made according to designs of Klusácek. The last window in the south of the nave, originally design of Cyril Bouda, was successfully completed only in 1992. The scene shows the meeting of Duke Oldrich with St. Procopius in the woods of Sázava.

The National Monument

|

It includes the third largest equestrian statue in the world- of Jan Žižka, who defeated King Sigismund in 1420 in the Battle of Vítkov Hill. The Monument also includes the Ceremonial Hall, an exhibition entitled "Crossroads of Czech and Czechoslovak Statehood", the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and other exhibition halls. Sadly, we got there too late to go into the halls or up to the observation platform on the top of the memorial.

The Monument was completed in 1938 in honor of the Czechoslovak legionaries. After 1948, it was used to promote the Communist regime. Between 1954 and 1962 it housed the mausoleum of Klement Gottwald. In 2000, the monument was acquired by the National Museum, which conducted a major restoration effort. After over two years of reconstruction, the Memorial was opened to the public on 29 October 2009.

|

A design contest was held for the design of two buildings; the first, to be located on Vítkov hill, was to be a monument to the First Resistance, and the second, sited at the foot of the hill, would be the Institute of Military History, housing the administration and museum. The architect Jan Zazvorka won first prize in the contest.

The construction of the museum at the foot of the hill was launched in 1927 and completed two years later. We passed this building on our way up the hill; the only indication of the fact that it was a military building was the the old tank on display next to the building. The construction of the National Liberation Monument commenced in 1928 when the cornerstone was laid on the top of Vítkov Hill in the presence of President T. G. Masaryk to mark the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the creation of Czechoslovakia. The shell was completed in 1933 and interior works continued, involving many leading artists, with essential completion coming in 1937.

When World War II began, the lower buildings of the museum, now the Institute of Military History, were seized by the Germans. The Monument's building escaped the Wehrmacht's attention until November 1942, by which time everything of value had been secretly removed. The building was then occupied by the German administration and until the end of the war the Wehrmacht used it for storage.

The Monument |

Ceremonial Doors |

The two photos above were taken on the plaza up the steps on either side of the equestrian statue. It was warm this afternoon, and it was nice to sit up in the shade of the giant horse and rider.

|

The monument was eventually commissioned in 1931 from sculptor Bohumil Kafka, a professor at Prague's Academy of Visual Arts. The sculpture was intended to be monumental and realistic. It took Kafka ten years to complete it, and an advisory board of nine people was established to supervise his work; the board included historians and hippologists (people who study horses). For this job, Bohumil Kafka had a new studio built, and he began work on model of a horse without the rider. Several men then modelled for the rider part, conceiving the rider's position, body and head. Experts in historical armament provided information not only on the rider's clothing style, but also many other details, such as the design of the foot frame. Kafka made a plaster model of Žižka's statue in November 1941 and died shortly afterwards.

|

Jeffie mentioned that she thought that this equestrian statue was the world's largest, or close to it, and that got me curious. As with most "records", it all depends on how you define "statue". When it is completed, the Crazy Horse Monument in South Dakota will be the world's largest equestrian figure, but it is being carved out of an existing rock face. Other statues are manufactured out of materials like concrete, and one of the largest of these is in China. But when you consider the typical bronze or iron statue that people think about, it turns out that this one is the third largest in the world. The world's largest equestrian bronze statue is that of Juan de Ońate (El Paso, Texas, 2006), and the second-largest is the statue in Altare della Patria in (Rome, 1911).

Fred and Jeffie at the Monument |

East End of the Monument |

We did walk down alongside the monument, which is when we found we couldn't get inside, so we continued to the east end of the building. There, we could see that there was a road up to the top of the hill, and a circular drive and fountain by the monument.

|

In the second half of the 19th century, Czech nationalism was displayed in historical places, among them Žižkov and Vítkov Hill. In 1877, the town of Kralovske Vinohrady I was renamed as Žižkov, as Jan Žižka of Trocnov, leader of the radical Hussites, was perceived as a symbol of the fight for Czech interests. In 1881 Žižkov was promoted to the status of a town. Vítkov was seen as a symbol of the Czechs and the ancient glory of the Czech nation, which led to the idea of building a monument to Žižka there. The initiative for building the monument is attributed to Karel Hartig, the first mayor of Žižkov.

The importance of the hill itself was further recognized when, in 1882, the Association for the Construction of the Žižka Monument in Žižkov was established; in 1910 a memorial tablet was unveiled at the top of the hill. The hilltop eventually became the site of not only the National Monument but also Žižka Monument (equestrian statue).

Walking Back to Jeffie's

|

Fred was taking other pictures as we walked, including one of a decorated train car coming out from the station. When we got down to street level and were walking along, Fred also photographed interesting building decoration (interesting because rarely to American buildings spend the money for such ornamentation). Here are more of his pictures:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

We got back to the Metro Station and then took the Metro to the stop nearest where Jeffie lives (which I've described on an earlier page). Jeffie wanted to walk back to her apartment to check on her cats before we had dinner, so we did that.

|

Finally, we headed over to the tram stop near the Church of St. Ludmila where we stopped at the gelato shop. We sat in the park eating our ice cream and making plans to see Jeffie after work tomorrow. Then she headed off back to her place and we hopped on the tram back to I. P. Pavlova and the Ibis Hotel.

It was another great day with Jeffie, but tomorrow we'll be on our own.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

May 29, 2017: Prague Castle and Petrin Hill |

|

May 27, 2017: Karlstein Castle; Troja Palace; Prague Botanical Garden |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |