|

May 31, 2017: Vysehrad Castle, St. Agnes' Convent and the Loreto |

|

May 29, 2017: Prague Castle and Petrin Hill |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |

It's Tuesday, and Fred and I are again on our own today; Jeffie has work to do this evening, so we will be on our own then as well. So we are going to visit a couple of Prague's highlights- the Charles Bridge and Old Town Square- but also wander around the areas where both are located to visit some other points of interest.

The Charles Bridge

We began early in the already-warming day, heading out from the Ibis Hotel to the Charles Bridge.

Getting to the Charles Bridge

|

From the metro station, which was the closest one to the Charles Bridge, we walked first west towards the Manesuv Most (the "Manes Bridge"), named for Josef Mánes (1820-1871)- a Czech painter who produced works in every genre from landscapes and portraits to ethnographic and botanical studies. He even did paintings of the twelve months for the face of the Prague Astronomical Clock. Although his work was little understood or appreciated in his lifetime, he is now considered to be among greatest Czech painters. The bridge bearing his name includes a statue of the painter at the Old Town end. (The bridge has a series of tall columns along each side of the bridge- eight in all.)

On the aerial view at left, you can see the route we took to get down to the Charles Bridge. We were able to walk along the river for quite a ways until we came to a point where a building came right to the water and we had to turn inland to finish our walk south to the bridge along the street that parallels the Vltava River.

There were some interesting things to see on the way, the first of which was the little park in front of the Rudolfinum. Here we found a fountain and some statues- including the one of Josef Mánes.

|

The Rudolfinum was designed by architect Josef Zítek and his student Josef Schulz, and it opened in 1885. It is named in honor of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, who presided over the opening. Between 1919 and 1941 the building was used as seat of the Czechoslovak parliament.

The Rudolfinum's Dvorák Hall is one of the oldest concert halls in Europe and is noted for its excellent acoustics. On January 4th, 1896, Antonín Dvorák himself conducted the Czech Philharmonic in the hall in its first ever concert. Dvorák has his own statue in Jan Palach Square.

The building also contains the Galerie Rudolfinum, an art gallery that focuses mainly on contemporary art. Major exhibitions have included works by famous Czech painters, photographers, and sculptors.

The Rudolfinum was quite a handsome building and we took quite a few pictures of it; the two below are the best:

|

|

From the Rudolfinum, we walked over to the other side of the Manes Bridge to the walkway and railing at the edge of the Vltava. Here, Fred got two good pictures of Prague Castle and the vineyards to the east of it:

|

|

From our position beside the river, I took two good panoramic shots. They are similar in that one covers part of the same area as the other, but each has its good points:

We walked down the riverside a ways, and I stopped again to get a picture of Fred with the Charles Bridge as a backdrop, and I made a movie as well, spanning the view from the Charles Bridge on the south to the Manes Bridge on the north.

Fred and the Charles Bridge |

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

We continued walking south along the river, coming back to the street along the river eventually to arrive at the East end of the bridge.

The East Portal of the Charles Bridge

|

We crossed the bridge from east to west, but before we did that, we spent a few minutes in the small square just east of the Old Town Bridge Tower (the bridge has three towers that were originally for protection; one of them is on the east end of the bridge and the other two are over in Lesser Town.

The square here on the east side is bordered on the north by the Charles Bridge Museum, on the east by the Church of Saint Salvator, and on the south by some commercial buildings (that actually extend out into the Vltava) and the Colloredo Palace- a landmark baroque palace that dates to the 1730s.

|

Next to the church is the motherhouse of the Knights of the Cross with the Red Star. This religious order originated in Bohemia, and is devoted mainly to offering medical care. Its members use the postnominal initials of O.M.C.R.S. Throughout its history it was accustomed to the use of arms, a custom which was confirmed in 1292 by an ambassador of Pope Nicholas IV. The grand master is still invested with a sword at his induction into office, and the congregation has been recognized as a military order by Popes Clement X and Innocent XII, as well as by several Holy Roman Emperors. This building is often referred to as the Crusaders Hospital, because the order used it to offer medical care to the Christian crusaders who came to the east to fight.

In front of the motherhouse is a large statue of Charles IV, for whom the bridge is named. Charles IV (1316-1378), was a King of Bohemia and the first to also become Holy Roman Emperor. He was a member of the House of Luxembourg from his father's side and the House of Premyslid from his mother's side, which he emphasised, because it gave him two saints as direct ancestors. Charles inherited the County of Luxembourg from his father in 1346, and the next year was crowned King of Bohemia. He was chosen by the prince-electors as King of the Romans in opposition to Emperor Louis IV. He was re-elected in 1349 and crowned King of the Romans. In 1355 he was crowned King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor. With his coronation as King of Burgundy in 1365, he became the personal ruler of all the kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire.

|

This church, which dates to the early 1600s, is considered to be one of the most valuable early Baroque monuments in Prague. It was formerly the primary church of the Jesuits in the Czech Republic. The church is currently used by the Roman Catholic Academic Parish, and is a venue for organ concerts. The organ, whose origins date back to the 17th century, was played in the 1880s by Jakub Jan Ryba, celebrated composer of the Christmas Mass “Hey, Master!”.

Both these buildings stand near the east gateway to the bridge. The Charles Bridge is the second oldest stone bridge in the Czech Republic. This connector across the Vltava River transports us not only from the Old Town to the Lesser Quarter, but also to the time of the coronation of Czech kings, who rode across Charles Bridge along the Royal Route.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

As we walked through the archway, Fred noticed and photographed the ornate underside of the arch. Just through the arch we came to the first of the many street performers and vendors that we saw as we crossed the bridge, and you heard them in the movie above. Here's a still shot of them and a look back at the Charles Bridge Museum:

|

|

Crossing the Charles Bridge

| The Statues |

The avenue of 30 mostly baroque statues and statuaries situated on the balustrades of the Charles Bridge forms a unique connection of artistic styles with the underlying gothic bridge. Most sculptures were erected between 1683 and 1714, and they depict various saints and patron saints venerated at that time. The most prominent Bohemian sculptors of the time took part in decorating the bridge, such as Matthias Braun, Jan Brokoff, and his sons Michael Joseph and Ferdinand Maxmilian.

Among the most notable sculptures, one can find the statuaries of St. Luthgard, the Holy Crucifix and Calvary, and John of Nepomuk. Well known also is the statue of the knight Bruncvík, although it was erected some 200 years later and does not belong to the main avenue. Beginning in 1965, all of the statues have been systematically replaced by replicas, and the originals are now in the National Museum at the top of Wenceslas Square.

I'd like to show you these sculptures, as between us we were successful in photographing all of them. In the scrollable window below, you'll find an aerial 3D view of the bridge, positioned initially at the west end. If you will click on any of the 30 marked statue positions, I'll show you our picture of that sculpture along with information about the subject(s) and the sculptor. Be sure to close each popup before you click on another statue.

| Scenes on the Bridge |

The Charles Bridge is probably Prague's second- or third-most-popular site; Prague Castle and Old Town Square are most likely the other two. The bridge is crowded all the time, we are told, and with all the street performers and crowds it's a great place for people watching. Here are some of the pictures we took on and from the bridge- and a movie you can watch:

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Here is a panoramic view looking downriver (north) with the Prague Castle in the background:

|

I did another panorama in the camera on the bridge, and it came out as if I had been using a fisheye lens, with this interesting result:

|

We of course continued across the bridge until we reached the West Portal.

The West Portal of the Charles Bridge

|

|

|

As we came off the bridge, I noticed this sign and I thought it was worth recording.

We walked through the archway through the one tower that is open for pedestrian traffic, and as we did so, we took some pictures of the two bridge towers above us; the design and ornamentation of both of them was quite intricate.

|

|

|

|

On the other side of the archway, we found crowds and a number of street performers. Here are some of them (the street performers):

|

|

|

As usual, Fred had his eye on a number of interesting architectural details, and he photographed quite a few of them. Here are three of the most interesting:

|

|

|

From here, we officially entered the Malá Strana district, and there were a number of things we wanted to see here.

The Malá Strana District (Lesser Town)

Malá Strana was founded by the King Ottokar II of Bohemia in 1257 by combining a number of settlements beneath the Prague Castle into a single administrative unit.

|

The market place, now known as Malostranské námestí (Lesser Town Square), was the center of the town. This square is divided into the upper and lower parts with the St. Nicholas Church in the middle.

In the picture at left, you are looking up the street that comes off the Charles Bridge; it is called Mosteca here, although further up its name changes to Malostranske. Up at the end of the street behind Fred you can see the Church of St. Nicholas, and we will visit it a little later on. It has a copper covered dome and a tall bell tower. Lesser Town Square is on this side and the other side of it, but we'll see that square later, too.

We are going to head to our left and go a ways south towards the Lennon Wall and another church we want to visit, but before we get off this main street, here are two other interesting views:

|

|

|

I've marked the two bridge towers, and the street performers were in the avenue just to the west of them. We walked up that street a ways and then turned south on the little side street that you can see. This brought us to the front of the Church of Our Lady Under the Chain, and we had a look inside.

I also walked up the street right in front of it to photograph an interesting statue that I noticed just a short distance to the west. Then I returned to the church and Fred and I walked around to the south of it to a little tree-shaded plaza where we found the Lennon Wall.

The Church of Our Lady Under the Chain

|

The original building was founded in the mid 13th century in place of a Romanesque basilica. The church was burned down twice. First during the Hussite riots in 1420, when the whole complex was gutted. After this fire, the church was transformed to Gothic style by the Knights of Templar, and most of the existing basilica was torn town. Construction though, was interrupted by the 15th century Hussite wars completing only the presbytery and the towers, which can be seen today. The church burned again in 1503. After that fire, a Baroque renovation of the church was carried out in 17th century probably by Carlo Lurago. Writings seem to indicate that the church is today not as ornate as it once was.

Its gothic past can be seen in the western face of the building with two much reduced steeples. It is these steeples on the west side, only about 90 feet high, that are referred to as “incomplete”. They were originally taller but after the blazes they were cut down. The prismatic steeple-towers are crowned with pyramidal roofs. Their original gothic windows are walled up. The steeples are supported by corner pillars.

The church, which is located between the streets Saská, Lázenská and a square called Velkoprevorské námestí, has several names. It is known as the church of Our Lady under Chain or church at “Bridge-End” and also as the church “at Maltese”. The gate of the monastery courtyard used to be locked by chain, and this fact is the basis of another theory as to how the church got its name.

|

Another interesting artwork found in the church can be seen in the picture at right. Look carefully at the second pillar from the front at the right side of the nave and you will see a sculpture on the wall of that pillar. It is about the same color as the pillar itself, so it may be hard to see. It is that of a man wearing a hat, and it is very unusual for a Catholic Church to allow any statue or depiction of a man with a hat. This artwork was originally intended to be placed in another area. But, apparently, the church fathers thought that making an exception in this case was warranted. The statue represents the hero who defended Prague against the Swedish army in 1848, Count Rudolf Colloredo-Wallsee.

Another piece of trivia involves the statue of St. John of Nepomuk on the Charles Bridge. That's the one that everybody touches for good luck. You may remember that the saint was the Czech martyr who refused to betray a confidence and was thrown to the Vltava river. As it turns out, he was arrested in this church.

When we came out of the nave, Fred photographed the two steeples from this side, and I photographed two of the statues on either side of the courtyard:

|

|

|

After we came out of the church, I walked a block west to Maltese Square, because I could see a large statue in the middle of it. Fred waited back by the church.

|

|

Many other interesting buildings line the square, such as the Rococo Palace of the Turbes, and the Nostic Palace, now the seat of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.

|

When we did come thorugh the square again, I had Fred stand by the entrance to the restaurant- mostly because of the horseheads that were decorating the building entrance.

In any event, after the Church of our Lady, we headed south of the church around the corner into another tree-shaded square for our next stop- the Lennon Wall.

The Lennon Wall

|

Since the end of World War II, of course, Prague, being in Czechoslovakia, was under the control of a Communist regime. As you might expect, dissent, and even views not thought in line with the "party line" were not tolerated openly. Criticism, basically, was not allowed. Beginning in the 1970s, young Czechs would write their grievances on this particular wall- usually under the cover of night.

The wall became a source of irritation for the communist regime of Gustáv Husák; in a report from the time it was recorded that the wall led directly to a clash between hundreds of students and security police on the nearby Charles Bridge. The movement these students followed was described ironically as "Lennonism" and Czech authorities described these people variously as alcoholics, mentally deranged, sociopathic, and agents of Western capitalism.

As for the slogans and grievances on the wall, the ruling party would periodically have the wall painted over so as to eliminate the slogans and their "subversive" effects. Persons present during these years said that the wall never stayed blank for more than a day or two; soon, new slogans would appear, the wall would become covered with them, and it would be once again painted over.

|

After the Revolution and the elimination of Communist rule, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the actual owners of the wall, let it be known that they would allow the graffiti to remain on the wall once it was added. They issued a statement that they would no longer paint over the wall, but allow anyone who wished to add his or her contribution. Of course, new images and slogans eventually had to be painted on top of older ones, but no one ever again simply painted over the images on the wall.

What this means, of course, is that the wall is continuously changing. One of the earliest items of grafitti, a portrait of John Lennon, is long lost under layers of new paint and/or new graffiti elements. Today, the wall represents a symbol of global ideals such as love and peace.

On 17 November 2014, the 25th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, the wall was painted over in pure white by a group of art students, leaving only the text "wall is over" [sic]. The Knights of Malta initially filed a criminal complaint for vandalism against the students, which they later retracted after talking with them. Days later, the wall was almost entirely covered again, and has remained so since.

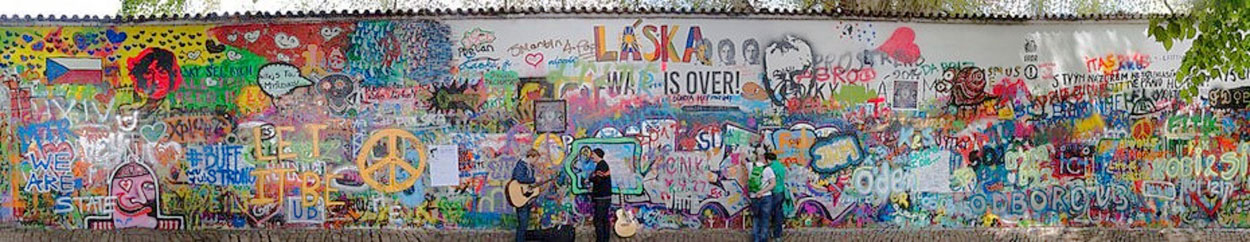

One thing I tried to do here at the wall is create a panoramic image of the whole thing. I couldn't use the camera to do it, as I could never get everyone away from the wall to allow me an unobstructed view. So what I had to do is walk slowly along the wall, staying at the same distance from it, and take a series of pictures that I could later stitch together. Even this process took some time, as there were so many people and I had to wait so often for them to move aside. As it was, even taking my time, I ended up with one person in my picture sequence, but perhaps it is good that she is there for scale. Here is that panorama:

Interestingly, compare my panorama from one I found from two years ago:

While I was concentrating on creating a panorama, Fred was busily photographing sections of the wall that he found interesting. His views were closeups, and it is easy to see the individual elements of the mural. Below is a slideshow of Fred's pictures. To go from one to another, just use the little arrows in the bottom corners of each image:

Finally, I want to include one other image for any of you who know that you won't get to the Lennon Wall in person, but who would like to examine it closely- all of it. In the scrollable window below is a large version of the panorama that I created. It is large enough that you should be able to read and see everything clearly. Just scroll back and forth and up and down to look at the entire mural:

From the Lennon Wall, we headed northwest towards the Lesser Town Square and the Church of St. Nicholas.

Malostranské námestí (Lesser Town Square)

|

|

We came into the square from the southeast corner; here is an aerial view of the square and the St. Nicholas Church complex in the middle of it.

|

|

In the aerial view you can see the Church of St. Nicholas and its Bell Tower clearly; we did not know it at the time, but you can ascend to the top of the tower for expansive views. (During the Communist era, the tower was closed because it was being used by the regime to keep watch on the American, Yugoslav and West German embassies which are also in Mala Strana a block or two south of the church. I like this picture that Fred took of some trams in Lesser Town Square; it struck me as very European.

Since we were in the square's northeast corner, we walked around the north side of the St. Nicholas Church complex to enter the east side of the square. (We were never sure whether that entire building you can see is all part of the church complex, but we assumed so.) Here we found a parking area and a monument.

|

|

This monument celebrates the end of a disease that plagued the city throughout the Middle Ages- the bubonic plague. After a late outbreak of the disease was finally under control, the city decided to erect the Plague Column to celebrate the end of the outbreak.

The column, which is also known as the Holy Trinity Column, was designed by Giovanni Batista Alliprandi. Built in 1715, the monument consists of a small fountain surrounded by putti. A large pedestal supports a soaring obelisk, which reaches a height of about 65 feet. The pedestal is decorated with statues created by Johann O. Mayer and Ferdinand Geiger. They depict patron saints including St. Wenceslas and St. John Nepomuk.

In the right-hand picture, you can see the towers of St. Vitus Cathedral up in the Prague Castle; this view probably gives you a better impression of how good the views of the city were from the castle itself. Here is Fred's picture of the northwest corner of the square, and again you can see St. Vitus Cathedral up on the hill.

The Church of St. Nicholas

|

In the second half of the 17th century the Jesuits decided to build a new church, and they chose Giovanni Domenico Orsi to design it. Orsi prepared plans for the church, but the Jesuits decided to build just one part of it first- the Chapel of St. Barbara. The order wanted to be able to begin conducting services as soon as possible. (In that chapel, visitors can see a copy of those original plans.)

The main church was built in two stages during the 18th century. The west façade, the choir, and the Chapels of St Barbara and St Anne were built between 1704 and 1711. The main cathedral and the other church buildings took the next 40 years to complete. (I continually find it remarkable how long it took to build edifices of this size in that time period. It makes me wonder how long it would take today to build exactly the same building in exactly the same way. I know that 100-story towers made of structural steel can be erected in about two years, but of course they aren't build of stone blocks.)

Count Wenceslaus Kolowrat-Liebsteinsky (1634-1659) from the prominent Czech House of Kolowrat was the largest patron of The Church of St. Nicholas. He donated his entire estate, worth 178,500 gold pieces (no idea what that would be in today's dollars), for the construction of the church and its adjacent buildings.

(Actually, I have tried to investigate, and the closest I can come to valuing the Count's estate is that a Bohemian thaler was, at the time, worth 2 guilders, and that a guilder would today be worth $36. So if we assume that a Bohemian thaler is the gold piece referred to, than we can multiply 178,000 by $72 to get the value of the Count's donation- some $12 million in today's dollars.)

|

The pillars between the wide spans of the arcade supporting the triforium were meant to maximize the dynamic effect of the church. The chancel and its characteristic copper cupola were built in 1737-1752, this time using plans by Christoph's son, Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer.

In 1752, after the death Dientzehofer in 1751, the construction of the church tower was completed. During the years the church continued to expand its interior beauty. Following the abolition of the Jesuit Order by Pope Clement XIV in 1755, St Nicholas became the main parish church of the Lesser Town.

The 250-foot-tall belfry is directly connected with the church’s massive dome. The belfry has a great panoramic view. Unlike the church itself, the Belfry is done in a Rococo style; it was designed by Anselmo Lurago and built between 1751 and 1756.

|

The interior is further decorated with sculptures by František Ignác Platzer; three of these sculptures are shown in my pictures at right.

The Jesuit Thomas Schwarz built the small and main organs as well as many others in Bohemia. The main organ here was built in 1745-47. The Baroque organ has over 4,000 pipes, the largest of which are almost twenty feet tall; it is located on a second level and we went upstairs to see it. This organ was actually played by Mozart in 1787. Mozart's spectacular masterpiece, Mass in C, was first performed in the Church of Saint Nicholas shortly after his visit. (Perhaps continuing the tradition of the Mozart concert, the Church of St. Nicholas is the venue for numerous concerts; a sign by the door when we entered listed five or six of them just in the next couple of weeks and over 120 more before the end of the year.

The Church of St Nicholas is a superb example of High Baroque architecture, a building that was incredibly beautiful inside, and monumental in its size. It is the most prominent and distinctive landmark in the Lesser Town, no panoramic view of the city would be complete without its silhouette below Prague Castle. Indeed, you saw it in a great many of our pictures from Prague Castle and from Petrin Tower. I want to include some more pictures from the interior of the church, and I will group them below.

Ceiling Frescoes

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interior Decoration

|

Here are more photos of the beautiful ornamentation of the walls and chapels:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

The many other paintings and frescoes in the church were the work of some ten different artists; all are among the best of their individual achievements. Another very interesting (and beautiful) feature was the ornate pulpit. The pulpit was crafted from artificial marble is decorated with the sculptures Allegory of Faith, Hope and Love and The Decapitation of St John the Baptist by Richard and Petr Prachner from around 1765. The pulpit’s elegant construction and fine ornamentation are unrivalled in Bohemia.

Finally, here are three more examples of the amazing ornamentation and craftsmanship in the church; all these views are towards the top of the walls of the nave and the chapels. You can see the ornate columns and frescoes; these repeated all around the chapel:

|

|

|

Side Chapels

|

|

|

|

Looking at these admittedly unprofessional pictures and snapshots, you should be able to realize that the St. Nicholas Church looks a lot better than even our photos indicate. We were also sorry that we didn't learn until later that one can climb the Bell Tower, 'cause we would have done that. But maybe we got enough views of Prague from above from the Zizkov TV Tower, the Clock Tower at St. Vitus Cathedral and the Petrin Tower.

Our next destination was Old Town Square, so we left the church and again walked down the north side of the church towards the Malostranska Metro station, intending to take it under the river and over to Old Town. Near the station, we came upon a small park that had an interesting monument at its center.

|

Inscribed on the monument in Czech and English is the following: "This monument is an expression of the British Community’s lasting gratitude to the 2,500 Czechoslovak airmen who served with the Royal Air Force between 1940 and 1945 for the freedom of Europe. Many were subsequently persecuted by the communist regime in Czechoslovakia. It was unveiled by the right honourable Sir Nicholas Soames MP on 17th June 2014. It is a gift to the Czech and Slovak peoples from the British community living and working in the Czech and Slovak Republics.".

During World War II, some 2500 Czech and Slovak men and women served in the British Royal Air Force as pilots, ground crew, administrators, and training personnel. About a fifth of them did not survive the war. (The RAF also included airmen from many other countries, and all earned a great reputation.) After February 1948 these Czechoslovaks who had served in the RAF became victims of the communist regime. Having lived in the West, and many of them had married English women and so were continually suspect. Almost all of the $100K cost of the monument was donated by the British community in the Czech and Slovak Republics, but donations from Czech citizens, businesses and individuals were also received.

From the memorial, we walked over to the Metro entrance and descended to the platform.

The Old Town of Prague

We took the Metro under the river to the Staromestska station and came up aboveground. We could see Old Town a few block east; we came into Old Town Square at its northwest corner at the St. Nicholas Church (not to be confused with the one we just left over in Mala Strana, Lesser Town). The Old Town of Prague is the medieval settlement that formed the original core of the city. It was separated from the outside by a semi-circular moat and wall, connected to the Vltava river at both of its ends. The moat is now covered up by the streets (from north to south-west) Revolucní, Na Príkope, and Národni— which remain the official boundary of the cadastral community of Old Town.

|

In 1338, the town bought a magnificent patrician house from the Wolfin family and rebuilt it into their town hall; the hall still exists today, and the Astronomical Clock Tower is a part of it. In the mid-14th century the importance of the Old Town of Prague increased rapidly. The city was prospering thanks to the development of trade and craftsmanship and became one of the most important Central European cities. When the Bohemian king Charles IV became the Roman Emperor in 1355, the attention of all medieval Europe was turned towards Prague, where his residence was located. That's when the original town hall was extended by an impressive square stone tower, a symbol of the power and pride of the town council of the first city in the Kingdom and Empire; when it was completed in 1364, it was the highest in the city.

The city expanded dramatically in the 14th century as the result of Charles IV's office (and with significant patronage from him). The New Town of Prague was founded (basically the area surrounding the original Old Town) and, since they were no longer essential, the moat and wall were dismantled. In 1357 work began on what is now the Charles Bridge, which connected the Old Town with the much newer Lesser Town of Prague. Much of the Old Town had to be rebuilt after the fire of 1689. Finally, in 1784, the four towns of Prague were united into the Royal Capital City of Prague with a common administration.

Using the square as our focal point, we plan on walking around and seeing as many of the notable sites as we can- most of which are marked on the aerial view above, left.

Old Town Square

When I took this picture, I was standing in front of the Church of St. Nicholas. The Kinsky Palace is directly in the middle of the picture, the spires of the Church of Our Lady Before Tyn are to the right, and the town hall and astronomical clock are just out of the view at the right. The memorial to Jan Hus is in front of the palace and the church.

|

Born in 1369, Hus became an influential religious thinker, philosopher, and reformer in Prague. He was a key predecessor to the Protestant movement of the sixteenth century. In his works he criticized what he saw as the religious moral decay of the Catholic Church. The Czech patriot believed that mass should be given in the local language, rather than in Latin. He was inspired by the teachings of John Wycliffe. In the following century, Hus was followed by many other reformers, such as Luther and Calvin. Hus was ultimately condemned by the Council of Constance and burned at the stake in 1415. This led to the Hussite Wars.

To the people of Bohemia and other regions around Prague, Jan Hus became a symbol of free thought and a symbol of strength against oppressive regimes. His opposition to church control by the Vatican gave strength to those who opposed control of Czech lands by the Habsburgs in the 19th century, and Hus soon became a symbol of anti-Habsburg rule. He is said to stand arrogantly in the square in defiance of the cathedral before him.

When Czechoslovakia was under Communist rule, sitting at the feet of the Jan Hus memorial became a way of quietly expressing one's opinion and opposition against the Communist rule. The memorial was restored in 2007.

|

All around the square there were beautifully restored buildings, and we took quite a few pictures of them.

Here are more of the pictures we took as we walked around Old Town Square:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

I did another panoramic view here in the square; this one looks towards the southeast corner:

The Church of Our Lady did not open until a set time in the afternoon, so we decided to first go see the Old Jewish Cemetery and have some lunch.

Jewish Town

|

In 1850 the quarter was renamed "Josefstadt" (Joseph's City) after Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor who emancipated Jews with the Toleration Edict in 1781. Two years before Jews were allowed to settle outside of the city, so the share of the Jewish population in Josefov decreased, while only orthodox and poor Jews remained living there.

Most of the quarter was demolished between 1893 and 1913 as part of an initiative to model the city on Paris. What was left were only six synagogues, the old cemetery, and the Old Jewish Town Hall (now all part of the Jewish Museum in Prague. Currently Josefov is overbuilt with buildings from the beginning of the 20th century, so it is difficult to appreciate exactly what the old quarter was like when it was reputed to have over 18,000 inhabitants.

We thought that we would just walk through the cemetery as we had walked through the newer one by Zizkov Tower, and perhaps go inside a synagogue, but we found that the only way to do either was to purchase a full tour ticket for the Jewish Quarter at $30 a pop. Not thinking this to be worth it, we returned to Old Town Square. Along the way to the Jewish Quarter and back, we concentrated on examining the architecture of this part of Prague, and took some good pictures.

|

|

I can't imagine that tours in these cars are cheap; the tours are very individual and personalized, since the cars can only carry a few passengers, but I'll bet that they are amazing to take. You'd get a tour guide and you wouldn't have to worry about navigating the transit system or continually consulting your tour map to see where you were or where you were going. The cars are also very picturesque, so it's a win-win for Prague's tourist industry.

Prague is known for its beautiful architecture. While most European cities have wonderful examples of old buildings, Prague seems to have modernized everything but its architecture. (There are skyscrapers, but they are almost all in a small area outside the touristy parts of town). Here are some of those beautiful examples:

|

|

|

Our return to the Square was down what was, apparently, one of Prague's most upscale shopping streets. All the high-end timepieces, clothing lines and accessories were prominently featured. I can only imagine how much this Da Vinci bag costs!

The Church of St. Nicholas

|

The church was formerly used by the Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church. Since 1920 it has been the main church of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church and its Prague diocese.

You can see another view of the Church taken from the east side of the square here.

The Church of Our Lady before Týn

|

Probably the best introduction to the church for you will be the one movie that I took from near the entrance- right under the oldest organ in Prague. In the movie, I tried to give a good impression of the vastness of the nave, ending up with a closeup of the main altar. It isn't my best movie ever; there were lots of folks crowded around this area taking their own pictures, and I was lucky none of them got in my way for the thirty seconds of film.

You can use the movie player at left to watch this movie of the inside of the Church of Our Lady before Týn.

So, how best to show you the interior of the church more close-up? As usual, I'd like you to feel that you were here with us and get as much information about the church as possible. In the case of this church, there were very informative signs at the front detailing the history and design of the church- and we photographed these.

|

I think that if you had been here, you would realize that as with many large, magnificent open spaces (inside or outside), pictures don't really do justice in comparison to what your eyes would reveal to you.

|

The other church we have to compare is the Church of St. Nicholas over in the Lesser Town. It was certainly impressive inside, but all the scaffolding up for the restoration of the ceiling frescoes spoiled any pictures we might have been able to take of the entire nave.

Even with me in the picture, though, it is hard not to be impressed with the opulence of the interior of this church. As I have been many times before, I am amazed at the amount of effort and money that must have gone into the construction and decoration of these monuments to a faith in something that can't be touched, felt, or seen. I have my own opinions, but whether the object of all this effort is real or not, you can't argue with the passion that must have gone into the creation of these monumental buildings.

As you can see from that last picture, photography was not allowed beyond the rope (and there was at least one official around to enforce the restriction). I can understand such restrictions when one is viewing copyrighted work, or when continued flash exposure might damage a painting, but I cannot for the life of me understand why photography without flash should be banned in a setting when taking pictures would neither interfere with the ability of other people to enjoy the space, or cause delays if one were on a guided tour. So I ignored the restriction, even though this meant that I had to avoid being obvious- a practice which meant that most of my pictures would not be as good as I might have wished.

|

|

The one other feature of the church that I need to describe is the organ that is installed in the loft over the west entrance to the nave. I took just one picture looking back from in front of the main altar, and I had to wait until the docent was out of sight before doing so. Here is my picture of the organ loft, and beside it a scrollable window with the sign describing it for you to read.

|

I have to say that I thought that the Church of Our Lady before Týn was one of the most impressive I have been in; I could only wish that our pictures would have been good enough to do it justice.

The Town Hall and Astronomical Clock

|

The oldest part of the Orloj, the mechanical clock and astronomical dial, dates back to 1410 when it was made by clockmaker Mikulás of Kadan and Jan Sindel, then later a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Charles University. The first recorded mention of the clock was in 1410. Later, presumably around 1490, the calendar dial was added and the clock facade was decorated with gothic sculptures.

In the early 1600s, wooden statues were added; figures of the Apostles were added after a major repair in 1787–1791. During the next major repair in the years 1865–1866 the golden figure of a crowing rooster made its appearance. The Orloj suffered heavy damage in May, 1945, during the Prague Uprising, when the Germans fired on the south-west side of the Old Town Square in an unsuccessful attempt to destroy one of the centers of the uprising. The hall and nearby buildings burned along with the wooden sculptures on the clock and the calendar dial face. After significant effort, the machinery was repaired and the wooden Apostles restored; the clock restored to operation in 1948.

The Orloj was renovated in autumn 2005, when the statues and the lower calendar ring were restored, and now, as we are visiting, you can see the scaffolding and coverings that will be part of this year's renovation which is already underway.

I know I often give a lot of explanatory detail about some of the places we visit and photograph, but in the case of the Astronomical Clock, trying to explain everything about its appearance and how it works would be overkill. There are lots of resources for that information if you are interested.

|

The bottom of the clock is the calendar board, which was added much after the upper two parts; it is thought this happenedd in about 1660. The original board was replaced by one made by the artist Josef Mánes in 1865. The board is about six feet in diameter and made of copper; it turns clockwise. Behind it is a second board that is stationary. (This board is actually stored in the Prague City Museum, and what we see on the tower is a copy.) The board has pictures of the individual months placed all around, each of them representing a certain pastoral motive. Underneath them smaller pictures show the signs of the Zodiac. On the edge of the big circle there is a church calendar composed of three hunded and sixty-five rays with the names of the saints and all the fixed holidays. Every day the little hand in the upper part of the calendar selects one of these rays.

|

|

At the top of the clock are two windows (and an animated figure above them). Every hour, statues representing the twelve Apostles take their turns at the two windows, with all twelve presented every hour. We stayed across an hour mark, and we were able to watch the Apostles move, and perhaps I should have filmed them, but I thought that they were too far away, and that having to hold the camera steady for a minute or so on maximum zoom would have been tough.

Between those two elements is the the astronomical dial- a form of mechanical astrolabe, a device used in medieval astronomy. You could also think of the Orloj as a primitive planetarium, displaying the current state of the universe. The astronomical dial has a background that represents the standing Earth and sky, and surrounding it operate four main moving components: the zodiacal ring, an outer rotating ring, an icon representing the Sun, and an icon representing the Moon. Refer to Fred's great closeup below a I describe this part of the clock.

The background represents the Earth and the local view of the sky; the blue circle in the center is the Earth, and the upper blue area is the portion of the sky which is above the horizon. The other areas indicate portions of the sky below the horizon. During each 24-hour period, the sun moves atop on setion or the other. Written on the backgrounds are "aurora" (dawn), "ortus" (rising), "occasus" (sunset), and "crepusculum" (twilight). The golden Roman numerals at the outer edge are the timescale of a normal 24-hour day and indicate local Prague time. The curved lines mark out 1/12 of the time between sunrise and sunset, and vary as the days grow longer or shorter during the year.

|

Above the background is a movable circle marked with the signs of the zodiac so that the sun's position can be tracked. You'll notice that the sections are unequal; this results from the use of a stereographic projection of the ecliptic plane using the North pole as the basis of the projection. This is commonly seen in astronomical clocks of the period. Find the small gold star over the background (currently at the right side of the background near Roman numeral VII); it shows the position of the vernal equinox, and sidereal time can be read on the scale with golden Roman numerals. The zodiac is on a 366-tooth gear inside the machine, and connected to the sun gear and the moon gear by a 24-tooth gear.

The golden Sun moves around the zodiacal circle, and its arm shows the time in three different ways: (1) the Roman numerals indicate local Prague time, (2) the curved golden lines indicate the time in unequal hours, and (3) the position of the golden hand over the outer ring indicates the hours passed after sunset in Old Czech Time. As if that weren't enouogh, the distance of the Sun from the center of the dial shows the time of sunrise and sunset. The Sun and its hand are on the 365-tooth gear inside the machine.

Finally, there is the hand for the Moon. It's position on the ecliptic is shown similarly to that of the Sun, although the speed is much faster (due to the Moon's own orbit around the Earth). The Moon's arm is on the 379-tooth gear inside the clock machine. The half-silvered, half-black sphere of the moon also shows the Lunar phase as it is on a gravity-powered screw-thread that slowly rotates. This last wrinkle, added by an unknown maker in the mid-17th century and accurate to one day in 3000, makes the Orloj unique in the world among astronomical clocks.

Walking Through Old Town

One of the stores we passed was called Captain Candy, where all kinds of candies and sweets were in filled treasure chests; it was all sold by the pound and all the same price. I found some of the sourest candy I'd had in a while; it was amazing. The pictures we took along the way were of whatever seemed interesting or otherwise photogenic. Here are just a few of those pictures:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Following our noses, we came out at the Vltava River right at the east gate to the Charles Bridge, so we had to turn north to get back to the Staromestska metro stop. Again, we went right over to the river so we could walk along it and enjoy the views.

|

|

Then we arrived back at the square where we'd started out this morning. We'd passed what we thought was just a civic sculpture, but which turned out to be a memorial to Jan Palach. Palach (1948 – 19 January 1969) was a Czech student of history and political economy at Charles University in Prague. He committed self-immolation as a political protest against the end of the Prague Spring resulting from the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies that ended the liberal reforms of Alexander Dubcek.

Palach set himself on fire in Wenceslas Square, and there is another, more famous monument to him in front of the National Museum. According to a letter he sent to several public figures, he demanded the abolition of censorship and a halt to the distribution of Zprávy, the official newspaper of the Soviet occupying forces. In addition, the letter called for the Czech and the Slovak peoples to go on a general strike in support of these demands. Palach died from his burns in hospital several days after his act. Palach's funeral turned into a major protest against the occupation. A month later another student, Jan Zajíc, burned himself to death in the same place, and others followed.

|

The installation with its symbolic flames is augmented by a plaque with the poem ‘The Funeral of Jan Palach’ by American writer David Shapiro:

|

When I entered the first meditation I escaped the gravity of the object, I experienced the emptiness, And I have been dead a long time.

When I had a voice you could call a voice,

|

I’ll follow you on foot. Halfway in mud and slush the microphones picked up. It was raining on the houses; It was snowing on the police-cars.

The astronauts were weeping,

|

Our stop at the Palach memorial was a somber end to the day, and it was our last photograph of the day as well. We headed back to the Ibis to relax for a while. Jeffie had business to do this evening, so we would have dinner on our own- the only time we did that in Prague. We went back to Old Town to a restaurant we'd passed in the afternoon and had one of the largest hamburgers I have ever seen- with fries and all the fixings. It was a traditional Czech restaurant, but we eschewed the Czech specialties for a taste of home.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

May 31, 2017: Vysehrad Castle, St. Agnes' Convent and the Loreto |

|

May 29, 2017: Prague Castle and Petrin Hill |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Prague |