|

June 4, 2017: Our Return Home |

|

June 2, 2017: A Walking Tour of Istanbul |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Istanbul |

Jeffie arrived last night, and today is our only full day with her here in Istanbul, so we plan to see as much as possible. Fred and I held off on touring the Old City (places like Topkapi Palace, the Hagia Sophia, and the Blue Mosque) as this was the area that Jeffie would want to see as well. So we plan to spend our entire day in the Old City. After that, Jeffie made a surprise suggestion that turned out to be one of the highlights of our entire trip to Europe.

Gülhane Park

We met in the lobby of the Nippon Hotel about 8:30AM to get an early start on the days activities. Jeffie and I consulted the tourist map and a transit map we got at the front desk to plot our route over to our first stop- Topkapi Palace.

|

|

As we had yesterday, we saw quite a few cats as we walked down the hill; they were everywhere, but particularly on the quiet side streets. Most of them were in sleep mode, but a few were walking around, and at least two of them were friendly enough to let Jeffie pet them.

Just before we reached the avenue by the Bosphorus, I asked Fred to stop so I could get a picture of him on the street coming down the hill. When we got to the avenue we discovered that our sense of direction had been spot on, as we were right across the street from the Kabatas tram stop. We'd learned yesterday about how to buy tickets and the machines, so we didn't have any problem getting them this morning. We went out onto the platform to consult the route map and await the arrival of our tram. It came in a few minutes, and we took it all the way down past Galata Tower and across the Galata Bridge (actually the tram bridge right next to it) where there were already folks fishing off the bridge.

|

Here is the actual Gulhane tram stop after both trams have moved on and we ourselves are a short ways up the street.

We found ourselves on a tree-shaded street that ran alonside the outer wall of Gulhane Park, and to get to the actual entrance we had to go a couple hundred feet up the street. Across the street as we walked Fred noticed an interesting entrance- to what, we really didn't know. But Fred was interested in the Islamic decoration above the gate, and he took a closeup view of it.

Here are a couple of pictures of Jeffie and I on the street and consulting a map of the park and Topkapi Palace:

|

|

Up at the corner, we turned to our left, and noticed that there seemed to be some sort of rounded, turreted building built into the wall of the park, and just beyond it we found a pylon describing what it was.

|

The Pavilion itself was reached from the palace by a wide ramp that crossed the parkland; the building itself was composed of a round sultan room and service buildings. The top of the pavilion was covered by a wide canopied bulbed- a slotted, lead-lined cone. Inside the building this cone was open and easily visible.

As you saw yesterday, the sultans eventually moved their residence and administrative office to the Dolmabahce Palace- the palace we toured yesterday. This meant that the original pavilion ceased to be required for its original function. The building then became a telegraph office within the ministry of communication.

The telegraph office was eventually removed as new technologies made it obsolete, and the building fell into disuse. In the first years of the Republican Era, it was allocated to the Association of Fine Arts. In 1938, it again became part of the Topkapi complex, which was now a museum, and it received a thorough restoration. in 1960. At that time, some wooden floors and sections that had been added over the years were removed, and the building returned to its original appearance.

It is currently administered by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism as Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar Literature Museum; this use began in 2011 and continues today.

Coming around the corner, we came to the entrance to Gülhane Park. This greenspace is historic, in that it was part of the Topkapi Palace complex. The south entrance of the park is one of the larger gates of the palace complex. Gülhane Park is the oldest and one of the most expansive public parks in Istanbul. There were three large archways in this section of the wall, any of which will bring you into the park. Right inside this wall was an entry plaza, and the park stretched away to the north. As we headed in, I turned to look back through another of the archways, and just happened to frame Mom's Corner Restaurant in the opening. An odd name for a restaurant in Istanbul, I think!

|

Gülhane Park was once part of the outer garden of Topkapi Palace and mainly consisted of a grove. A section of the outer garden was planned as a park by the municipality and opened to the public in 1912. The park previously contained recreation areas, coffee houses, playgrounds etc. Later, a small zoo was opened within the park. The first statue of Atatürk in Turkey was erected in the park in 1926, sculpted by Heinrich Krippel.

The park underwent a major renovation in recent years; the removal of the zoo, fun fair and picnic grounds effected an increase in open space. The excursion routes were re-arranged and the big pool was renovated in a more modern style, resulting in a long undulating pool; in the wide sections fountains were installed, and at the narrow points picturesque wooden bridges cross from one side of the pool to the other. The removal of most of the concrete structures from the park brought back the natural landscape of the 1950s, revealing trees dating from the 1800s.

The Museum of The History of Science and Technology in Islam is located in the former stables of Topkapi Palace, on the western edge of the park; You can see some of those buildings in the background of the picture, which looks kind of northwest. The museum was opened in May 2008 by the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan; it features 140 replicas of inventions of the 8th to 16th centuries, from astronomy, geography, chemistry, surveying, optics, medicine, architecture, physics and warfare.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

We did not walk a long way through the park; at the beginning were all the pools and fountains and it looked as if most of the park was broad pathways and old trees- certainly a nice oasis in the bustling city. From the top of the park, I made a 360° panorama, with the entrance at both ends of the image. That panorama is in the scrollable window below:

|

We took a number of other pictures as we wandered around this beautiful oasis, including a few of another of those "living walls" that we saw from the taxi on our ride into the city two days ago.

|

|

|

Enjoy wandering around Gulhane Park with us for a while, before we head up to the palace.

We are going to leave the park now, go back out the entrance, and then head up a small street to Topkapi Palace and Museum.

The Topkapi Palace and Museum

The Topkapi Palace (locally, the Seraglio) is a former palace and now a large museum. In the 15th century, it served as the main residence and administrative headquarters of the Ottoman sultans.

Entering the Topkapi Palace: The First Courtyard

|

Off to our right was a stone wall, and at one point a spot where it looked as if there used to be some doorways, as you could still see the brick arches that would have been above them.

One odd thing was that along the side of the street along here were a number of what looked like very old fragments of stone- pieces of columns, pediments, lintels and walls, and many other objects- including some sort of tub. We weren't at all sure (and still aren't) whether these were old or just made to look that way. If they were really old, you'd think they would have been in a warehouse somewhere, but then again, maybe they aren't being harmed by being outside (being made of stone and all). We took a bunch of pictures of them, and here are a couple:

|

|

We continued up the street and through the archway, finding on our left some interesting sculptures on the outside of a building. Further along, we stopped to look back down the street towards the park. Then we came out into an open area that turned out to be right in front of the entrance to Topkapi Palace. There I stopped to photograph the area in panorama:

We were indeed now right in front of Topkapi Palace. The name of the palace used to be Saray-i Cedid-i Amire; that name was employed until the 18th century. The palace received its current name during Mahmud I's reign, when the name of a seaside palace (Topkapusu) was given to it (that seaside palace having been destroyed in a fire). In Turkish the current name of the palace, Topkapi, means "Cannon Gate".

|

We actually didn't know it at the time, but our walk up from the park had brought us into what is called the First Courtyard of Topkapi Palace. Surrounded by high walls, this area functioned as an outer precinct or park and is the largest of all the courtyards of the palace. The steep slopes leading towards the sea were terraced, and some of the historical structures that were here are gone now. Remaining are the former Imperial Mint, the church of Hagia Irene (which was to our right and which we would pass later) and various fountains. Here are some of the pictures we took in the First Courtyard:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

We could see ahead of us that there was a line of people at what appeared to be a series of ticket windows. We didn't know whether there was a charge to enter, but assumed as much. I went over to investigate and found that there were all kinds of tickets you could buy for the sites all along this part of the old city- individual entries, combination tickets, tourist passes, and so on. Had I known what we would know by the end of the day, buying a combination ticket would have saved us maybe $10 each over the individual tickets we bought during the day, but that was of little consequence. I went ahead and bought individual entries for Topkapi, eschewing special tickets for guided tours. As it turned out, most things were well-marked and we also encountered all kinds of tours going on and could not avoid overhearing much of what those guides were saying.

I'll talk more later about the First Courtyard when our tour through Topkapi itself is done and we walk through it again towards the first gate of the palace, but for now let's just head inside through the Gate of Salutation.

In the Second Courtyard

|

We'll return to the First Courtyard when we leave Topkapi and walk down to the Imperial Gate, but for now we can trace our progress through the Second Courtyard and our visits to some of the buildings that surround it.

When we first entered the courtyard, I stopped to take a picture of what must have once been a huge tree, but which appeared to have been either damaged or destroyed at some point. I just thought it an interesting view, and you can have a look at it here.

|

We reached the corner of the courtyard at the entrance to the Harem. We had not bought tickets for that tour, so we just had a look around this area. The long colonnaded building at the north side of the courtyard used to be the Imperial stables, now used as a temporary exhibition hall.

|

The Tower of Justice is several stories high and the tallest structure in the palace, making it clearly visible from the Bosphorus as a landmark. The tower was probably originally constructed under Mehmed II and then renovated and enlarged by Suleiman I between 1527 and 1529. Sultan Mahmud II rebuilt the lantern of the tower in 1825 while retaining the Ottoman base. The tall windows with engaged columns and the Renaissance pediments evoke the Palladian style.

|

There are multiple entrances to the council hall, both from inside the palace and from the courtyard. The porch consists of multiple marble and porphyry pillars, with an ornate green and white-coloured wooden ceiling decorated with gold. You can see another, different view of that ceiling here. The exterior entrances into the hall are in the rococo style, with gilded grilles to admit natural light. While the pillars are an earlier Ottoman style, the wall paintings and decorations are from the later rococo period.

The Imperial Council building was first built during the reign of Mehmed II, but the present building dates from the period of Süleyman the Magnificent, as it had to be restored after the Harem fire of 1665. It has been restored numerous times; there are verse inscriptions on the facade that mention the restoration work carried out in 1792 and 1819. The rococo decorations on the façade and inside the Imperial Council date from this period.

An Entrance to the Imperial Council |

Inside the Imperial Council |

Inside, the Imperial Council building consists of three adjoining main rooms; there was also a room with a wooden portico that was used by the council as a mosque. One chamber was where the Imperial Council held its deliberations; the second was occupied by the secretarial staff; the third was where the head clerks kept records of the council meetings. We all thought that the interior decoration was pretty amazing; here is a selection of some of the best pictures we took inside the Imperial Council:

|

|

Coming out of the Imperial Council, we began to work our way around the northeast corner of the Second Courtyard towards the Felicity Gate which would take us further into the palace.

|

|

This treasury was used to finance the administration of the state and for the storage of valuable objects. The treasury was closed by the imperial seal entrusted to the grand vizier. In 1928, the palace's collection of arms and armor was put on exhibition in this building. I took a good many pictures inside, but the darkness and uselessness of the flash for glass-encased objects marred almost all of them. You can see the two best pictures here and here.

Located outside the treasury building is a target stone, which is over eight feet tall. This stone was erected in commemoration of a record rifle shot by Selim III in 1790. It was brought to the palace from Levend in the 1930s.

|

|

The Sultan used this gate and the Divan Meydani square only for special ceremonies. The Sultan sat before the gate on his Bayram throne on religious, festive days and accession, when the subjects and officials performed their homage standing up. The funerals of the Sultan were also conducted in front of the gate.

On either side of this colonnaded passage, under control of the Chief Eunuch of the Sultans Harem and the staff under him, were the quarters of the eunuchs as well as the small and large rooms of the palace school.

The small, indented stone on the ground in front of the gate marks the place where the banner of Muhammad was unfurled. The Grand Vizier or the commander going to war was entrusted with this banner in a solemn ceremony.

The Third Courtyard

|

|

The ceiling of the chamber was painted in ultramarine blue and studded with golden stars. The walls were lined with blue, white and turquoise tiles. The chamber was further decorated with precious carpets and pillows. The chamber was renovated in 1723 by Sultan Ahmed III, destroyed in the fire of 1856 and rebuilt during the reign of Abülmecid I. It is the location of the main throne room is located inside the audience chamber. According to contemporaneous accounts, the room and the Emperor's throne were plain in construction but exceeding rich in decoration- including gold cloth, numerous precious stones, many cushions "of inestimable value", mosaic-covered walls, a fireplace of silver, and a fountain embedded in one wall. Little of this richness is visible today; the reconstructions toned it down considerably.

|

|

Behind the Audience Chamber on the eastern side is the Dormitory of the Expeditionary Force, which houses the Imperial Wardrobe Collection. This collection is made up of around 2,500 garments, invluding the precious kaftans of the Sultans. It also houses a collection of 360 ceramic objects. The dormitory was constructed under Sultan Murad IV in 1635. The building was restored by Sultan Ahmed III in the early 18th century. The dormitory is vaulted and is supported by 14 columns. Adjacent to the dormitory, located northeast, is the Conqueror's Pavilion, which houses the Imperial Treasury.

In the northeast corner of the Third Courtyard we found the Privy Chamber (actually three of them), one of which houses the Chamber of the Sacred Relics. The chamber was constructed by Sinan under the reign of Sultan Murad III. It used to house offices of the Sultan.

|

Several other sacred objects are on display, such as the swords of the first four Caliphs, The Staff of Moses, the turban of Joseph and a carpet of the daughter of Mohammed. Even the Sultan and his family were permitted entrance only once a year, on the 15th day of Ramadan, during the time when the palace was a residence. Now any visitor can see these items, although in very dim light to protect the relics (which is why I have no pictures, since flash was forbidden), and many Muslims make a pilgrimage for this purpose. The Privy Chamber was converted into an accommodation for the officials of the Mantle of Felicity in the second half of the 19th century by adding a vault to the colonnades of the Privy Chamber in the Enderun Courtyard.

The Arcade of the Chamber of the Holy Mantle (seen at the right side of the picture at left and more fully here) was added in the reign of Murad III, but was altered when the Circumcision Room was added. This arcade may have been built on the site of the Temple of Poseidon that was transformed before the 10th century into the Church of St. Menas. It has a beautiful floor made of contrasting pebbles. You can see a nice picture of Fred's showing the design of the floor here. We went through the Treasury to enter the Fourth Courtyard.

The Fourth Courtyard

|

|

As you can easily see from the picture above, right, of Jeffie and myself, the views from the long terrace that ran across the south side (actually southeast side) of the Fourth Courtyard were pretty neat, and we stayed here a while just admiring the view.

|

|

Down below the terrace we could see old ruins of some of the structures that pre-dated this part of the palace. The promontory that the palace is on seems to be an excellent strategic location, so I imagine that it has been used and re-used many times over the centuries. I let my little camera do its panoramic thing to come up with this good view of the terrace area:

In the view above, that is a cafe down the stairs just below us. You can see that the views are pretty amazing from here.

|

And here are some of the other good pictures we took on the terrace:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

We walked down to the end of the terrace and then turned to come back around in front of the Grand Kiosk (Mecidiye Kiosk) built by Sultan Abdül Mecid I in 1840 and the last significant addition to the palace. It was used as an imperial reception and resting place because of its splendid location, giving a panoramic view on the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus. The sultans would stay here whenever they visited Topkapi from their seaside palaces. The building is in an eclectic mixed European-Ottoman style, and was occasionally used to accommodate foreign guests.

From here we made our way to the other side of the courtyard (heading north), and we passed the gate that leads from the palace down into Gulhane Park:

|

|

That's the park that we walked through before coming up here to Topkapi Palace; it used to be the imperial rose garden, which belonged to the larger complex of the palace. As we began to head across towards the buildings on the north side of the courtyard, I stopped to take four pictures that I put together in the panoramic view that's in the scrollable window below:

|

At the left you can see the sides of the buildings bordering the Third Courtyard, and one of the passages back up to that area. Next, to the right and ahead of us is the Yerevan Kiosk; we will be heading up some stairs at the side of it to get to the plaza on the north side of the courtyard; you can see a bit of that plaza to the right of that Kiosk. Next is the Baghdad Kiosk which is on that plaza level. You might also make out the fountain ahead of us, to our right, and below that kiosk. The white building with the curtained windows is the Terrace Kiosk and the colonnade that leads to the last building, at the right of the image, which is the Tower of the Head Tutor/Physician.

The rectilinear Terrace Kiosk was a belvedere (a building constructed to take advantage of a scenic view or garden view) built in the second half of the 16th century. It was restored in 1704 by Sultan Ahmed III and rebuilt in 1752 by Mahmud I in the Rococo style. It is the only wooden building in the innermost part of the palace. It consists of rooms with the backside supported by columns.

|

As we got to the end of the walk through the garden, I could get a better view of the Baghdad Kiosk and the fountain below it; that is the view that you can see at left.

We came below the Yerevan Kiosk and admired its outside decoration. It turned out to indeed have great views. Then we walked up the stairs to the Marble Terrace to look around. In the center of the plaza there is a pool with a unique fountain in the middle (sculpted in the form of one of the nearby buildings); the Circumcision Room was on the other side to the left, and the Baghdad Kiosk was to the right. Here are two views of that plaza:

|

|

We crossed the plaza first to go to the railing on the other side; it looked as if there might be good views from here, and we could tell that the views would be up the Golden Horn. The views were indeed very impressive, and here are three of them:

(When looking at the picture above, I noted the Galata Tower right of the middle of the picture, and this recalled a photo that we took while we were up in that tower two days ago. At the time, I wasn't sure what we were looking at, but now I know: we were taking a zoom picture of exactly where we were standing right now. You can see that picture here. You will see the Baghdad Kiosk at the left, the gilded gazebo in the center, the Circumcision Room to the right of that and then the buildings of the Harem. Very interesting.

|

|

Here are two good pictures of the actual plaza and observation point where we were standing:

Iftar Kiosk, Circumcision Room and Harem |

Baghdad Kiosk |

The small gilded gazebo is actually interesting. Called the Iftar Bower, it was a first in Ottoman architecture with echoes of China and India. The sultan is reported to have had the custom to break his fast under this bower during the fasting month of Ramadan after sunset. Some sources mention this resting place as the "Moonlit Seat". Special gifts like the showering of gold coins to officials by the sultan also sometimes occurred here. The marbled terrace gained its current appearance during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim (164048).

Below left is a view of our next stop, the Baghdad Kiosk, taken from near the pool and fountain here on the plaza level. (I also want to include a picture of the Baghdad Kiosk that we took as we were coming up the stairs to the plaza level. We walked over to the entrance to the Baghdad Kiosk, and I could get another nice view looking down at the garden fountain and Sofa Kiosk.

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

From the Baghdad Kiosk, we walked back across the plaza past the pool and to the Circumcision Room. The entrance to this pavilion is off a corridor between it and the Yerevan Kiosk; the walls of that corridor are decorated in all manner of beautiful tiles and gilded grilles.

|

These once embellished ceremonial buildings of Sultan Suleiman I, such as the building of the Council Hall and the Inner Treasury (both in the Second Courtyard) and the Throne Room (in the Third Courtyard). They were moved here out of nostalgia and reverence for the golden age of his reign. You can see this re-use of old materials inside the room; there are places where there are many different tiles right next to each other on walls and ceilings.

These tiles then served as prototypes for the decoration of the Yerevan and Baghdad kiosks. The room itself is symmetrically proportioned and relatively spacious for the palace, with windows, each with a small fountain. The windows above contain some stained-glass panels.

On the right side of the entrance stands a fireplace with a gilded hood. Sultan Ibrahim also built the arcaded roof around the Chamber of the Holy Mantle and the upper terrace between this room and the Baghdad kiosk. The coffered ceiling was particularly beautiful.

|

You can have a look at the only interior picture we took in the Yerevan Kiosk here.

And here are some additional pictures of the area outside the Yerevan Kiosk and the Circumcision Room, taken just before we began to make our way back to the entrance to Topkapi Palace:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

From the Yerevan Kiosk, we made our way back through the Fourth and Third Courtyards, and back out to the Second Courtyard, just inside the entrance of Topkapi Palace.

Leaving the Yerevan Kiosk |

Back in the Second Courtyard |

There, we walked past the Treasury pavilion again and back out to the center of the courtyard, where Fred took a nice picture of the Tower of Justice and I took a last panoramic view of the Second Courtyard:

|

Then we left Topkapi Palace proper, heading back out into the first courtyard (actually outside the paid admission area) and, following our map of the old city, headed south towards the Hagia Sophia.

Along Council Street to the Hagia Sophia

The main street leading to Topkapi Palace is the Byzantine processional Mese avenue, known today as Council Street. This street was used for imperial processions during the Byzantine and Ottoman era. It leads directly to the Hagia Sophia and turns northwest towards the palace square to the Fountain of Ahmed III.

|

|

The church, originally built in the 4th century and the first church in Constantinople, was dedicated by Constantine to the peace of God, and is one of the three shrines which the Emperor devoted to God's attributes, together with Hagia Sophia (Wisdom) and Hagia Dynamis (Power). The building reputedly stands on the site of a pre-Christian temple. The original church was burned during the Nika revolt in 532; although Hagia Sophia was completed in 537, the Emperor Justinian I had this church rebuilt in 548. It was then damaged by an earthquake in 740; the Emperor Constantine V ordered restorations made, and had its interior decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Some restorations from this time have survived to the present.

|

The Justinian restoration established a cross-domed plan on the gallery level while still being able to keep the original basilica plan at the ground level. The narthex can be found to the west, preceded by the atrium, and then the apse on the east side.

Hagia Irene still holds its dome and has peaked roofs on the north, west, and south sides of the church. The dome itself is 45 feet wide and over 100 feet high and has twenty windows. Hagia Irene has the typical form of a Roman basilica, consisting of a nave and two aisles, which are divided by three pairs of piers. This helps support the galleries above the narthex. Semicircular arches are also attached to the capitals which also helps give support to the galleries above.

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, the church was enclosed inside the walls of the Topkapi palace and the cross on top of the dome was replaced by the symbol of Islam, the crescent moon. The Janissaries used the church as an arsenal until 1826, and it was also used as a warehouse for military equipment and repository for trophies of arms and military regalia taken by the Turks. During the reign of Sultan Ahmet III (17031730) it was converted into the National Military Museum in 1726. It was used as a military museum of one kind or another until 1978 when it was turned over to the Turkish Ministry of Culture.

|

The Imperial Gate is the main entrance into the First Courtyard. The sultan would enter the palace through the Imperial Gate, which is actually located southwest of the actual palace.

This massive gate, originally dating from 1478, is now covered in 19th-century marble. Its central arch leads to a high-domed passage; gilded Ottoman calligraphy adorns the structure at the top, with verses from the Qur'an and tughras of the sultans. The tughras of Mehmed II and Abdül Aziz I, who renovated the gate, have been identified.

According to old documents, there was a wooden apartment above the gate area until the second half of the 19th century. It has been used used as a pavilion by Mehmed, a depository for the properties of those who died inside the palace without heirs and the receiving department of the treasury. It has also been used as a vantage point for the ladies of the harem on special occasions. Passing through this gate marked the actual end of our visit to Topkapi Palace.

|

|

The Fountain of Sultan Ahmed III (in Turkish: III. Ahmet Çesmesi) is a major fountain located in the great square just in front of the Imperial Gate. It is a good example of Turkish rococo style.

|

The fountain kiosk of Ahmed III is located in the place of a Byzantine fountain known as Perayton. Another fountain, built during the Byzantine Empire stood on the site before this fountain. The architectural features of the exterior reflect a synthesis of traditional Ottoman and contemporary western styles. (And in popular culture was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 10 lira banknotes of 1947-1952.)

The fountain is a large square block built with five small domes. Mihrab-shaped niches are decorated in low relief with foliate and floral designs in each of the four façades, and each contains a drinking fountain. The water is supplied from an octagonal pool inside the kiosk, with circulation space around it for kiosk attendants. On each corner is a triple-grilled sebil (from which an attendant issued cups of water or sherbet, free of charge, from behind a grille). Sadly, no sherbet today.

Above the drinking fountains and niches on each façade and sebil are large calligraphic plates bordered with blue and red tiles. Each plate bears stanzas of a 14-line poem dedicated to water and (not unsurprisingly, the donor of the plates). It is read clockwise around the fountain, beginning at the northern sebil. The last stanza of the poem the northwest façade is a chronogram composed by Ahmed III. I have a closer view of the fountain showing some of this detail, and you can see it here.

I didn't actually realize it at the time, but the fountain and Council Street ran right behind the Hagia Sophia; it was the huge building with four towers that was right next to us. So before we head down the street to get around to the front of the Hagia Sophia, here are two views of it from here. The left-hand view, below, is a composite of two pictures, but since I was so close to the building, when they were merged the perspective was severely curved. I have tried to straighten it out as much as I can, but I really needed to be further away.

|

|

We walked southwest on Council Street, and took a detour in to see the tombs of the Sultans. There are five tombs belong to Ottoman Sultans and their family members in the historical buildings adjacent to the Hagia Sophia Museum. All the restorations were completed fairly recently, and the buildings have been opened to the public (subject to Islamic regulations, of course).

|

Council Street is the walkway that is at the left side of the picture, angling up and to the right. We entered the complex via a passageway between two buildings in the lower left of the image. As you can see, the five tombs are arranged around a courtyard, oriented so that most of the tombs face the Hagia Sophia which is the large structure at the right of the picture and, apparently, the vantage point from which this picture is taken.

I have marked the five tombs in case you are interested, but since I don't exactly recall in what sequence we looked at or went inside the tombs, I won't try to put any kind of route on the picture.

Restoration of the tombs (and of some of Hagia Sophia) was actually funded by what we would call the estate of Sultan Mehmet; while the restoration of Hagia Sophia is ongoing, the tombs are essentially finished. Items found during the restorations clarified the sepulchral culture of the Ottomans. All wraps and clothes which were found in tombs are in museums, but have been replaced with identical replicas. Although tombs are named after Sultans, tombs were also shelters for the members of their families and their dynasty. It is also known that after Sultan Selim II the Sultan's wives were buried in the same tomb with him.

One tomb that I took the trouble to go inside (and by "trouble" I mean that I had to remove my shoes and leave them outside) was the tomb of Selim II; this building has beautiful examples of stonework, woodwork, tiles and calligraphic arts.

|

|

The building has an octagonal plan covered with two domes, supported by half-domes and eight columns facing the internal walls. The facade of the building is covered with marble panels and there is a three-arched small porch at the front. The entrance door of the structure has inlaid mother of pearl and decorated with geometrical tortoiseshell- one of the techniques which would identify the building as one of Sinan's designs. Each side of the door has tiled panels with purple, blue, green and red flower patterns which show 16th century tile workmanship.

|

Here are some additional views of the inside of this tomb:

|

|

Some of the tombs were closed, but in any event we didn't want to go inside all of them, so we just wandered around the courtyard looking at the architecture. The Princes Tomb and the tomb of Sultan Murat III were adjacent, so we visited them next.

|

|

The entrance to the tomb is nicely-decorated with interlocking wooden laths in geometrical shapes. All interior walls are decorated with plant motifs, hand drawn ornaments, ribbons and flowers in baskets. In the Tomb of Princes, 4 princes and the daughter of Sultan Murat III are buried. I made my only "tomb" movie inside the Tomb of Princes (as it was the only one with a lot of light), and you can use the player at right to watch it. I was also able to get a good picture of the ceiling in the Tomb of Princes.

The tomb of Mustafa I was another prominent one, but it was closed. We were able to have a look at its richly decorated portico ceiling. Fred took a good picture of two of the major tombs- the Tomb of Mustafa I and that of Murat III, and you can see that picture here.

|

|

From here, we could see one of the four towers and many of the high windows of the structure. But none of this really prepared us for what the church was like inside; that would be the next stop we made.

So we left the tombs of the Sultans and went back out to Council Street. We rounded a corner and walked north to the ticket office and entry for the Hagia Sophia.

The Hagia Sophia Basilica, Mosque, and Museum

The Hagia Sophia was a Greek Orthodox basilica, later an imperial mosque, and now a museum. It was the Roman Empire's first Christian Cathedral; from the date of its construction in 537 until 1453 it served as an Eastern Orthodox cathedral and seat of the Patriarch of Constantinople (except between 1204 and 1261, when it was converted by the Fourth Crusaders to a Roman Catholic cathedral). It was converted into an Ottoman mosque in 1453, but in 1931 was secularized and opened as a museum. Famous in particular for its massive dome, it is considered the epitome of Byzantine construction and is said to have "changed the history of architecture". It remained the world's largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years, until the Cathedral at Seville was completed in 1520.

Entry

|

We walked south on Council Street from Topkapi, stopped at the tombs, and then walked around the south side of the Hagia Sophia complex and then north again to the entrance. It was along this street south of the complex that I came upon an interesting picture of an Istanbul municipal employee hard at work. South of the Hagia Sophia there is a huge open area, and we could see the Blue Mosque and a very large fountain in the distance. We learned later that this area is Sultan Ahmet Square which, as it turned out, we would visit a bit later.

We came to the southwest corner of the complex where we turned north again, following the crowd to get to the ticket kiosk. As it turned out when I inquired, we would have done marginally better to buy a combination ticket when we were at Topkapi Palace, as we were still intending to go to the Blue Mosque, but it wasn't a big difference so we just bought single tickets again.

From our position near the ticket kiosk, we could see pretty much all of the Hagia Sophia complex, although with our cameras it was impossible to get it all in, as close as we were and with all the crowds around. I did try to take a picture of Hagia Sophia over everyone's heads, but I was only moderately successful. We could look to our right and see the Tombs of the Sultans- the area we had just left- and another small, interesting structure.

|

His successor, Sultan Mahmud I (1730-1754) added, in 1740, a Sadirvan (a fountain for ritual ablutions). This fountain is a masterpiece of Ottoman Architecture and one of the largest and most beautiful fountains in Istanbul. It is covered by a dome and an eave mounted on eight columns with muqarnas headings and eight arches.

On the dome, there are a bronze tulip scripture of "Allah" written by carving in stack on top and a mirror scripture of "Muhammed" below and an "eulogium" on the upper and inner part of marble arcade. The fountain has 16 slices and each slice has a bronze tap in the middle. There are tulip-shape bronze banners containing the scripture of "We have created everything from water" on the upper part of the joining section of sliced bronze water mains over the taps.

We reached the head of the entry line and had our tickets scanned and were then able to enter the complex proper. Fred got a nice picture of the Sadirvan and part of the Hagia Sophia in the background, and you can see that picture here. The first church on the site was known as the "Great Church" because it was larger than any in the city. Inaugurated in 360 it was built by Constantius II (some say Constantine the Great)near the developing palace. It and the nearby Hagia Eirene that we saw earlier acted together as the principal churches of the Byzantine Empire. In the riots that occurred when the Patriarch of Constantinople John Chrysostom was sent into exile in 404, this church was largely burned down, and nothing remains of it today.

A second church on the site was ordered by Theodosius II, who inaugurated it in 415. But a fire that started during the tumult of the Nika Revolt and burned the second Hagia Sophia to the ground in 532. Several marble blocks from the second church survive to the present; among them are reliefs depicting 12 lambs representing the 12 apostles. Originally part of a monumental front entrance, they now reside on a small plot adjacent to the museum's entrance, and we took a couple of pictures of them:

|

|

Just past these fragment, we came to what is at the moment the main entrance to the Hagia Sophia museum- four arched doorways between the monumental height of four buttresses providing support for the dome and upper stories of the Hagia Sophia.

|

|

This hall would presumably have served the same function as a lobby serves today- a place for worshippers to gather before a service or, when the building was used as a mosque, a place for them to remove footgear before entry. At one end of the hall there was an entrance to the area that would have been used by women, and there was also an entrance to the ramp/stairway leading up to the second level.

But before we go there, we'll spend time investigating the huge open area under the Hagia Sophia dome.

The Domed Interior/Nave

|

In 726, the emperor Leo the Isaurian issued a series of edicts against the veneration of images, and so all religious pictures and statues were removed from the Hagia Sophia. A great fire in 859 damaged the structure, and an earthquake in 869 made one of the half-domes collapse. Repairs were made, but when the Western dome arch collapsed in an earthquake 120 years later, the Emperor Basil II ordered more permanent repairs. His architect reinforced the fallen dome arch, and rebuilt the west side of the dome with 15 dome ribs- these repairs taking six years to complete. The church's decorations were renovated and the church reopened in 995.

Upon the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, the church was ransacked and desecrated by the Crusaders, and in 1204 it became a Roman Catholic cathedral. After the recapture in 1261 by the Byzantines, the church was in a dilapidated state; in 1317 new buttresses were built, but earthquakes in 1344 led to the collapse of several parts of the building and its closure until repairs began in 1354.

Constantinople fell to the attacking Ottoman forces in 1453; as per Ottoman custom, Sultan Mehmet II allowed his troops three full days of pillage and looting in the city. Hagia Sophia became a focal point as the invaders believed it to contain the greatest treasures and valuables of the city. When Sultan Mehmet II entered the church, he insisted that it should be converted into a mosque at once (although the conversion took some time). Since the church was again in such poor repair, the Sultan ordered a renovation to accompany the conversion.

The first minaret was erected by 1481 and another by 1500. After earthquake damage, both were replaced about 1550 by new structures at the east and west corners of the building. At about that same time the mihrab was added; this is a structure placed inside a mosque to indicate the direction of Mecca, and thus the direction in which prayers should be made. The two colossal candlesticks in that picture were brought back from the conquest of Hungary by Suleiman the Magnificent around 1555. By 1575, the structure had been strengthened by an earthquake engineer, and two more minarets were added.

|

The final 100 years of the Hagia Sophia's life as a mosque saw more renovations and considerable upkeep. Most of the interior decoration we see today dates from this period. The mosaics in the upper gallery were exposed and cleaned; we will see some of them shortly. The old chandeliers were replaced by new pendant ones and new gigantic circular-framed disks or medallions were hung on columns; you can see examples of both of these in the picture at right.

The medallions were inscribed with the names of Allah, Muhammad, the first four caliphs and Muhammad's two grandchildren by the court calligrapher. In 1850 the architects Fossati built a new sultan's lodge behind the mosque, and renovated the minbar (the pulpit or lectern in the mosque where the imam stands to deliver sermons. The term is derived from the Arabic root "to raise, elevate". The mihrab we see today was the result of these renovations as well.

Outside the main building, the minarets were repaired and altered so that they were of equal height. When these restorations were finished in 1849, the mosque was reopened and used without any other significant change until 1935.

|

|

|

For all that, the structure continued to deteriorate. The building's copper roof had cracked, causing water to leak down over the fragile frescoes and mosaics. Moisture entered from below as well. Rising ground water had raised the level of humidity within the monument, creating an unstable environment for stone and paint. The World Monuments Fund raised money to stabilize and repair the cracked roof, and then it employed and trained young Turkish conservators in the care of mosaics.

By 2006, the WMF project was complete, though many other areas of Hagia Sophia continue to require significant stability improvement, restoration and conservation. Haghia Sophia is currently the second most visited museum in Turkey, attracting almost 3.3 million visitors annually.

Although use of the complex as a place of worship (mosque or church) was strictly prohibited, in 2006 the Turkish government allowed the allocation of a small room in the museum complex to be used as a prayer room for Christian and Muslim museum staff, and since 2013 from the minarets of the museum the muezzin sings the call to prayer twice a day. Competing groups are pushing for the restoration of the building as a church or a mosque, reflecting the schism within the country itself. It appears that the movement to make the Hagia Sophia a mosque again is in the ascendancy.

|

|

|

While minbars are akin to pulpits, they have a function and position more similar to that of a church lectern, being used instead by the minister of religion, the imam, typically for a wider range of readings and prayers. Minbars seem to be very similar from one mosque to another- usually shaped like a small tower with a pointed roof and stairs leading up to it. In contrast to most Christian pulpits, the steps up to the minbar are usually in a straight line on the same axis as the seat. Here in the Hagia Sophia, the really odd thing was the cats; we had no idea if they were representative of something cultural, save for the fact that cats are all over Istanbul.

|

The interior here is decorated with mosaics and marble pillars and wall coverings of great artistic value. The temple itself was so richly and artistically decorated that Justinian proclaimed, "Solomon, I have outdone thee!". Justinian's basilica was at once the culminating architectural achievement of late antiquity and the first masterpiece of Byzantine architecture. Its influence, both architecturally and liturgically, was widespread and enduring in the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Muslim worlds alike.

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome which at its maximum is 182 ft from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Repairs to its structure have left the dome slightly elliptical, with the diameter varying by about a foot as you go around its base. At the western entrance side and eastern liturgical side, there are arched openings extended by half domes of identical diameter to the central dome, carried on smaller semi-domed exedras; you can see some of those half-domes here. All this results in a clear internal span of some 250 feet. Interior surfaces are sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple porphyry, and gold mosaics (particularly on the second level, as we will see shortly).

|

The Hagia Sophia is noted for its huge dome, and that dome has been of particular interest for many art historians, architects and engineers because of the innovative way the original architects envisioned it. The dome is carried on four spherical triangular pendentives, one of the first large-scale uses of them. The pendentives are the corners of the square base of the dome, which curve upwards into the dome to support it, restraining the lateral forces of the dome and allowing its weight to flow downwards. Large buttresses were used to reinforce it.

The weight of the dome remained a problem for most of the building's existence; the damage to it over the years was mentioned above- most of which was caused by earthquakes. So many repairs have been made that only two sections of the present dome date from the 562 reconstruction.

Although the reconstruction stabilized the dome and the surrounding walls and arches, the actual construction of the walls of Hagia Sophia weakened the overall structure, as the bricklayers used more mortar than brick and did not allow enough time to let the mortar cure. When the height of the dome was raised, the lateral, outward-pushing forces were reduced, and the weight transmitted more effectively down into the walls. Moreover, the new ribs inside functioned like an umbrella; these ribs allow the weight of the dome to flow between the windows, down the pendentives, and ultimately to the foundation.

Hagia Sophia is famous for the light that reflects everywhere in the interior of the nave, giving the dome the appearance of hovering above. This effect was achieved by inserting forty windows around the base of the original structure. Moreover, the insertion of the windows in the dome structure lowered its weight.

I will freely admit that many of the pictures we took in the nave were repetitive; the ones already used above are certainly representative, but there are duplicated views even there. That said, I want to include yet a few more views of the inside of this amazing structure- not necessarily so that you can look at each and every one of them, but because I want them to be part of our memory of this visit:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

The Gallery Level

|

In that picture, you can see many of the features that we saw when we were on the main floor- including the minbar and the mihrab which are at the far end of the museum floor; you can see both those features in the picture at left. Here are some additional views taken from this balcony:

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Standing on the second floor balcony and facing the front of the church/mosque, we could see that the second floor balcony actually continued around both sides of the space; the only place that there was no second floor was over the front of the church (where a Christian altar might be, and where here the mihrab was). To our left, on the north side of the structure, the balcony was closed off; that's where all the scaffolding was. But we could go around to our right, and so that's where we headed next.

In the gallery, there were of course impressive views down into the nave, but there were also much closer views of the underside of the dome and the half-domes surrounding it:

|

|

The upper gallery is laid out in a horseshoe shape that encloses the nave until the apse. Several mosaics are preserved in the upper gallery, an area traditionally reserved for the Empress and her court. Fortunately, the best-preserved mosaics are located here in the southern part of the gallery.

|

In Byzantine art, and later Eastern Orthodox art generally, the Deisis is a traditional iconic representation of Christ in Majesty or Christ Pantocrator: enthroned, carrying a book, and flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist, and sometimes other saints and angels. Mary and John, and any other figures, are shown facing towards Christ with their hands raised in supplication on behalf of humanity.

This scene has become a standard in many Eastern churches, and is usually displayed in the same way- above the level of the doors but below the row of figures depicting the Twelve Great Feasts. Seven figures, usually one to a panel, became standard; on Christ's right would be Mary, the Archangel Michael and Saint Peter, and on his left John the Baptist, the Archangel Gabriel and Saint Paul. Local traditions often included other figures as well. In Western churches, it became more common to see the Four Evangelists and/or their symbols included around Christ, but still this Deisis composition was common (especially in any areas with Byzantine influence), often forming part of a scene relating to Judgment Day. The use of the scene declined through the Middle Ages, and so from the Reformation onward, new churches used it only rarely.

|

On either side of His head are the monograms IC and XC, meaning Iesous Christos. He is flanked by Constantine IX Monomachus and Empress Zoe, both in ceremonial costumes. Constantine is offering a purse, as symbol of the donation he made to the church, while Zoe is holding a scroll, symbol of the donations she made.

Constantine IX Monomachos (c. 1000 1055) reigned as Byzantine emperor from 1042 to 1055. He had been chosen by the Empress Zoe as a husband and co-emperor in 1042, although he had been exiled for conspiring against her previous husband, Emperor Michael IV. They ruled together until Zoe died in 1050.

The inscription over the head of the emperor says: "Constantine, pious emperor in Christ the God, king of the Romans, Monomachus", and the inscription over the head of the empress reads as follows: "Zoe, the very pious Augusta".

This mosaic was modified at some point when the previous heads were scraped off and replaced by the three present ones. Perhaps the earlier mosaic showed Zoe's first husband Romanus III Argyrus or her second husband Michael IV. Another theory is that this mosaic was made for an earlier emperor and empress, so when the new ruling family arrived, it was thought decorous to make the change. There seemed to be plenty of wall space around, so I found myself wondering why a new mosaic was not simply created.

|

On her right side stands emperor John II Comnenus, represented in a garb embellished with precious stones. He holds a purse, symbol of an imperial donation to the church. John II (1087 1143) was Byzantine Emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as "John the Beautiful" or "John the Good", he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Irene Doukaina and the second emperor to rule during the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. John was a pious and dedicated monarch who was determined to undo the damage his empire had suffered following the battle of Manzikert, half a century earlier.

Empress Irene stands on the left side of the Virgin, wearing ceremonial garments and offering a document. Their eldest son Alexius Comnenus is represented on an adjacent pilaster. He is shown as a beardless youth, probably representing his appearance at his coronation at age 17.

In this panel one can already see a difference with mosaics like the Zoe mosaic just a century older. More realistic expressions are used in the portraits, instead of the idealized forms used earlier. As part of this more realistic tone, the empress is shown with plaited blond hair, rosy cheeks and grey eyes, revealing her Hungarian descent, and the emperor is depicted in a dignified, rather than stilted, manner.

|

The first runic inscription was discovered in 1964 on a parapet on the top floor here in the southern gallery, and the discovery was published by Elisabeth Svärdström in "Runorna i Hagia Sofia" in 1970. The inscription is so worn down that today only "-ftan", which is the Norse name Halfdan, is legible. The remainder of the inscription is considered to be illegible, but it is possible that it followed the common formula "NN carved these runes".

At right you can see Fred kneeling by the parapet and pointing to the rune. I know you can't see it clearly in that picture, but if you will click at the end of Fred's outstretched fingers, I will show it to you in closeup.

A second inscription was discovered by Folke Högberg from Uppsala in 1975. It was discovered in a niche in the western part of the same gallery as the first inscription. The discovery was reported to the Department of Runes in Stockholm in 1984, but it was not published. The archaeologist Mats G. Larsson discovered the runes anew in 1988 and published them in 1989. He read and interpreted it, but scholars are still uncertain whether his interpretations are correct. In fact, many scholars think it not to be an intentional rune at all, but rather the Viking equivalent of graffiti.

Other archaeologists have made copies of five other possible runic inscriptions on the parapet and these were handed over to the Norwegian Runic archive in 1997. There may be additional runic inscriptions waiting to be found on the walls and other parts of the Hagia Sophia.

I have a few final pictures from the upper gallery that I want to include here so as to record the beautiful decoration of the columns and arched ceilings:

|

|

|

|

|

Leaving the Hagia Sophia

We came back out into the area at the front of the Hagia Sophia where the entry halls are, and at that point we had Jeffie take two more pictures of the two of us:

|

|

We were at a different end of the hall at the front of the church, and in this area there were a number of exhibits that we hadn't seen on the way in to the Hagia Sophia earlier. One was the very interesting snake patterned bowl. We had a look and then went back out one of the front entrances, sat down at a cafe and had a cold drink.

|

|

|

The Hagia Sophia was pretty much as amazing as I thought it would be. The only bad thing was that in pictures and movies I'd seen of the structure, there was no scaffolding and no ongoing construction to mar the beauty of the interior. I understand the need for the constant maintenance of the structure- certainly its history of repeated damage makes that need obvious. I might wish, though, that we'd had the good fortune to visit before this current renovation began, or perhaps after a round of it was over. But those are the breaks, and certainly out tour of the interior was only marginally affected.

After we were refreshed, we left the grounds of the Hagia Sophia, continuing southwest across a large park to the Blue Mosque.

Sultan Ahmed Archaeological Park

At first, I thought that the beautiful fountain and park southwest of the Hagia Sophia was an attraction of its own, which I found was referred to at the Sultan Ahmed Archeological Park on various maps.

|

Actually, I learned that the Hagia Sophia, this park and fountain, the Blue Mosque and the Hippodrome (which we'll visit a bit later) are all part of what's called Sultanahmet Square, and this name refers to the old historic quarter of Istanbul where these and other historic buildings and monuments are located. Walking through this park and past the fountain, we had good views of the Hagia Sophia behind us and the Blue Mosque the Blue Mosque ahead of us. Here are some other views of those two structures:

Here is a very nice panorama that I took as we headed across the park to the Blue Mosque. The Hagia Sophia is at the left, and the picture pans about 270° around through the south and west to take in the Blue Mosque:

We then headed across the park to get a closer look at the fountain and an interesting building on the southeast side of the square.

|

|

This 250-foot long structure is designed in the style of classical Ottoman baths having two symmetrical separate sections for males and females. The exterior walls are built in courses of one cut stone and two bricks. In this bath, each section has a changing room, hot room, and cool room.

The men's and women's sides are the same. The changing room is rectangular and covered with a dome; it has pointed-arch niches in each of its four sides. The cool room is roofed with three domes and a door leads in the cross-shaped hot room, which has four loggias with fountains in the corners, and four self-contained cubicles for retreat under a small dome. In the center is the "tummy stone" on which bathers can lie. The large dome of the hot room, which sits on the octagonal-shaped walls, has small glass windows to create a half-light from top. This building stood closed a long time and was used as a warehouse. In 2007, Istanbul city authorities decided to return the hamam to its original use, and after a 3-year, $11 million restoration project regained its former glory when it was reopened in 2011. (A bath cycle is about $100.)

|

|

But for an extremely casual photographer (more of a "snapshotter", in truth) they may be OK, and they certainly achieve their purpose for me, which is to add a bit of action to my photo album, helping me remember the "feel" of some of the places we've visited. So at right is a player for the movie that I made here, and I hope you'll watch it so you can hear and feel what it was like to walk across the square.

About halfway down to the Blue Mosque, I stopped to try to make an almost 360° panoram of the square. I kept messing up and not moving the camera steadily or some such, but I finally ended up with a nice result that is just shy of my 360° target;

We continued through the square down to the Blue Mosque- one of the "must-sees" in Istanbul.

The Blue Mosque

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque is an historic mosque and popular tourist site. The Blue Mosque, as it is popularly known, continues to function as a mosque today; men still kneel in prayer on the mosque's lush red carpet after the call to prayer. The mosque was constructed between 1609 and 1616 during the rule of Ahmed I. In addition to the areas of prayer, it ontains Ahmed's tomb, a madrasah and a hospice. Hand-painted blue tiles adorn the mosques interior walls, and at night the mosque is bathed in blue as lights frame the mosques five main domes, six minarets and eight secondary domes.

|

The mosque is oriented northwest-southeast, with the "back" of the mosque being on the southeast side. Our route brought us to the mosque from the park adjacent to it. Just before we entered the front courtyard, Fred turned back to get an excellent picture of the Hagia Sophia. We came through a passage that brought us into this courtyard, and so of course we spent some time walking all the way around it, counterclockwise, from our entry point. From the entry, we turned right to walk along the eastern arcade wall (heading north if you want to refer to the aerial view). From a point almost at the northeast corner of the three-sided arcade, here is a view looking back at the east side of the arcade and the mosque.

After we'd seen the outside of the mosque, we made our way to the entry building on the southwest side of the mosque proper, entering via a ramp and doorway on that side of the structure. We viewed the inside of the mosque as we crossed over to the exit back on the northeast side of the structure.

On the outside of the arcade, right where we came in, the old elementary school is now used as an information center that provides visitors with an orientational presentation on the Blue Mosque and Islam in general.

The Courtyard

|

|

The central hexagonal fountain is small relative to the courtyard. The monumental but narrow main gateway to the courtyard is located on the north wall, and it stands out architecturally with its small, ribbed semi-dome.

|

All around the walls of the courtyard arcade wings there were exhibits of information about the mosque. These covered its history, the various renovations that have been undertaken (including the current one), and its use today. While they may be repetitive, either Fred or I took a picture looking along each of the sides of the courtyard arcade. The first one looks north from our entrance, another looks across the north wall (and you can see the unimposing main entrance on the north side), and the third looks along the west wall. In another picture taken from a position along the west wall, you can look northeast to the north and east courtyard walls, and you can see the minaret in the northeast corner of the complex.

|

|

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque is one of the three mosques in Turkey that has six minarets. According to folklore, an architect misheard the Sultan's request for "altin minareler" (gold minarets) as "alti minare" (six minarets); at the time, only the Ka'aba mosque in Mecca had such a feature. When criticized for his presumption in equalling the Mecca mosque, the Sultan then ordered a seventh minaret to be built at the Mecca mosque.

Four minarets stand at the corners of the Blue Mosque itself, and two more at the far corners of the courtyard. Each of these fluted, pencil-shaped minarets has three balconiesthree balconies (the two at the courtyard corners have only two balconies). The muezzin or prayer caller had to climb a narrow spiral staircase five times a day to announce the call to prayer. Today, a public address system is being used, and the call can be heard across the old part of the city, echoed by other mosques in the vicinity. Large crowds of both Turks and tourists gather at sunset in the park facing the mosque to hear the call to evening prayers, as the sun sets and the mosque is brilliantly illuminated by colored floodlights. We should have come back for that.

I want to include one panoramic view of the courtyard, taken from the east wall:

We exited the courtyard at the southwest corner, and walked along the side of the mosque to the entry kiosk.

|

What, then, was the purpose of the check-in at this pavilion? It seemed as if its sole purpose was to ensure that anyone entering the mosque was properly attired. Men, for example, could not enter wearing shorts, and the kiosk provided baggy pants that could be worn over them. We saw one fellow arrive in a tank top and shorts; he was provided not only with the pants but with a loose shirt that he had to change into.

Everyone had to either remove their shoes and carry them, or put on a kind of shoe covering that presumably satisfies the Islamic rule that the inside of the mosque not come into contact with dirt from the outside. We opted to carry our shoes, and this made picture-taking inside a bit of a hassle.

But women are the main concern; all women have to be covered, head to foot, to enter the mosque. (In secular Islamic countries, they don't have to be so covered in public, but in some countries, of course, they must be covered any time they are outside their homes.) Jeffie, of course, had to avail herself of the loaner clothing that would allow her to not only cover her head, but also cover the bare part of her legs. (She chose the little booties to put over her street shoes.) That's her in her loaned attire coming up the steps as we entered the mosque for a look around.

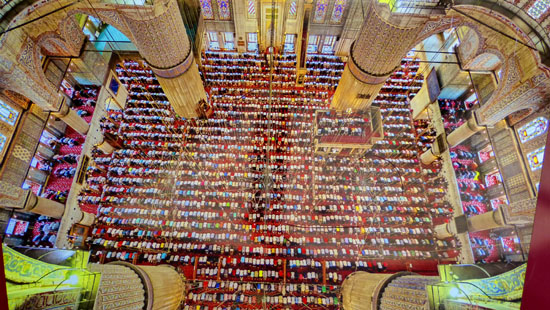

Inside the Blue Mosque

|

|

At its lower levels and at every pier, the interior of the mosque is lined with more than 20,000 handmade Iznik style ceramic tiles, made at Iznik (the ancient Nicaea) in more than fifty different tulip designs. The tiles at lower levels are traditional in design, while at gallery level their design becomes flamboyant with representations of flowers, fruit and cypresses. The tiles were made under the supervision of the Iznik master. The price to be paid for each tile was fixed by the sultan's decree, while tile prices in general increased over time. As a result, the quality of the tiles used in the building decreased gradually.

|

|

More than 200 stained glass windows with intricate designs admit natural light. Some closeups of a few good examples are above. But Fred took a picture with his "starburst" filter of two rows of windows, and it turned out really well.

|

And it wasn't just the lights themselves, but the wires hanging from the ceiling that were holding them up. Had it been just one wire for each of the huge chandeliers, perhaps you could overlook them. But even though each large circular light fixture could have been hung from just three of them and have been perfectly stable, it seems as if each one had a dozen or more wires going all the way up to the ceiling. Take Fred's picture of one of the beautiful columns for example. You want to examine and appreciate the column and its construction and decoration, but after a moment about all you can focus on are all the wires coming down from the ceiling.

The pictures really don't show them clearly, but on some of the fixtures there are ostrich eggs; these were originally used to avoid cobwebs inside the mosque by repelling spiders. Modern pest control techniques have obviated the need for them, but a few were left as a reminder of the past.

The decorations include verses from the Qur'an, many of them made by Seyyid Kasim Gubari, regarded as the greatest calligrapher of his time. The floors are covered with carpets, which are donated by the faithful and are regularly replaced as they wear out. The many spacious windows confer a spacious impression.

|

|

You can see the carpets in both those pictures. Of course, the second picture was taken in the visitor area; women are not allowed in the prayer area save for areas off to the side that are separated. Of the women visitors that you see here, some were Islamic women that were already dressed in either a full burqua or at least a hajab, but most were wearing the "loaned" garments.

|

The most important element in the interior of the mosque is the mihrab; this structure, placed at the front of the mosque, indicates the direction of Mecca, and so the direction in which Muslims should pray. In my picture, this structure is just to the right of center in the lower part of the picture.

The other important element is the minbar- the tall, stairwaylike affair that usually has a lectern at the bottom and a pulpit-like structure at the top. In this mosque, as in many of them, the pulpit is crowned with a conical shape. You can see the minbar in this mosque just to the right of the mihrab. This is where the imam stands when he is delivering his sermon at the time of noon prayer on Fridays or on holy days. The mosque has been designed so that even when it is at its most crowded, everyone in the mosque can see and hear the imam.

As I've said, visitors cannot go into the main prayer area. I suppose that if you were a muslim, and visiting Istanbul, that you would not be prevented from entering the vast prayer floor for one of the eight prayers during the day, but regular tourists, like ourselves, weren't allowed to enter. Because of that, I couldn't get any closer to the mihrab and minbar. But those two features are quite beautiful in this mosque, so I want to include a couple of pictures we took of pictures that we found in the courtyard exhibits. One shows the prayer floor full of the faithful, and the other shows the mihrab and minbar:

The Prayer Areas are Full |

The Mihrab and Minbar |

The walls and columns are sheathed in ceramic tiles. Although we could not get close enough to photograph it, there is a royal kiosk situated in the south-east upper gallery of the mosque. This royal loge is supported by ten marble columns and has its own mihrab.

I have a few other pictures that we took that I want to include here- along with my one movie.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Finally, here are two more pictures Fred took of the incredible decoration here inside the Blue Mosque:

|

|

We left the Blue Mosque on the opposite side of the building from where we entered, and there we stopped to put our shoes back on and for Jeffie to remove and return the loaned garments. Then we walked northwest between the mosque and an Islamic museum out to the area between the German Fountain and the Serpent Column- the ancient Hippodrome.

The Hippodrome

From the Blue Mosque, we walked over to an area that used to be the Hippodrome in ancient Constantinople. On the way, we passed an area just between the Blue Mosque and the park fountain that had rows of plain benches; none of us were sure what they were for. At the hippodrome, we wanted to look at the two columns that marked the ends of the former structure, as well as the German Fountain we'd seen in our little guide. We also found a small bazaar, so we walked through that as well.

|

The German Fountain

|

Wilhelm (and Prussia) were keen to construct the Baghdad Railway, which would run from Berlin to the Persian Gulf, and would further connect to British India through Persia. This railway could provide a short and quick route from Europe to Asia, and could carry German exports, troops and artillery.

At the time, the Ottoman Empire could not afford such a railway, and Abdülhamid II was grateful for Wilhelm's offer to finance most of the construction cost, but he was suspicious that the German's motives were more than just the economics of profiting from such a railway; Abdülhamid II's secret service believed that German archeologists in the Emperor's retinue were in fact geologists with designs on the oil wealth of the Ottoman empire.

That secret service uncovered a German report which noted that the oilfields in Mosul, northern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) were richer than those in the Caucuses- the most extensive known at the time. Even so, in his first visit, Wilhelm secured the sale of German-made rifles to Ottoman Army, and in his second visit he secured a promise for German companies to construct the Istanbul-Baghdad railway.

As a gesture for the 1898 visit, the German Government constructed this fountain for Wilhelm II and Empress Augusta to donate to the Ottomans. According to the Ottoman inscription, the fountain's construction started in 1898 with a planned inauguration in September of 1900- the 25th anniversary of Abdülhamid II's ascension to the throne. Construction was delayed, though, and the fountain was not inaugurated and presented to the Ottomans until January, 1901 (oddly enough on Wilhelm II's birthday.

The fountain was built only partially on site. Marble, stone and gem parts of the fountain were constructed in Germany and ransported piece by piece to Istanbul by ships. Some of the mechanical systems were also built in Prussia and transported to Istanbul. Much of the activity in the hippodrome was more in the nature of assembly.

|

|

The fountain was surrounded with a bronze fence, but it no longer exists. The outside of the dome is ornately patterned bronze; the dome's ceiling is decorated with golden mosaics and again with Abdülhamid II's tughra and Wilhelm II's symbol.

The bronze inscription on the reservoir (written in German) reads: "German Kaiser Wilhelm II endowed this fountain, in thankful remembrance of his visit in 1898 autumn, to the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II". There is also an Ottoman inscription in the arch of fountain- an eight couplet history verse that commemorates the construction of the fountain for Wilhelm II's visit to Istanbul. I do not know if drinking from one of the fountains is advisable, but Jeffie used one of them to at least wash her hands.

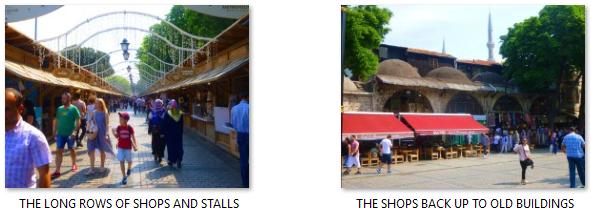

The Bazaar and Shops

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

Down at one end of the Bazaar near the Serpent Column, I found an interesting cafe, but it made me wonder where pessimists go to eat.

The Obelisk of Theodosius

|

As you have seen in movies I am sure, the "stadium" (which is actually the name for the geometric shape that consists of an elongated rectangle with semi-circles attached to each of the short sides) would have a central structure (like a spine and actually called the Spina) around which the horses and chariots would race. Oftentimes, there were monuments at either end of this structure or at various points along it. Here in the Istanbul hippodrome, three of these monuments still exist.

In the picture at left of the plaza where the Hippodrome once stood, you can see these monuments. In the nearground is the Obelisk of Theodosius, while in the background (at the far end of what would have been the spine) is the Walled Column. In the middle, barely visible, is the Serpent Column. We had a chance for a closeup look at each of these structures.

Over the centuries, the actual racetrack was buried further and further down as other structures where built and torn down on top of it. Today, the actual track is actually some six feet below the surface of the square. When the modern square was constructed, the course of the old racetrack was indicated with paving- and you can see that row of different pavestones in the picture. The three monuments I mentioned still sit on the Spina that is now six feet down, so walled holes have been made in the square so that you can still see down to their bases.

The Hippodrome was excavated in 1950-51. A portion of the substructures of the Sphendone (the curved end) became more visible in the 1980s with the clearing of houses in the area. In 1993 an area in front of the nearby Blue Mosque was bulldozed in order to install a public building, uncovering several rows of seats and some columns from the Hippodrome. Investigation did not continue further, but the seats and columns were removed and can now be seen in Istanbul's museums. It is possible that much more of the Hippodrome's remains still lie beneath the square.

|

|

The other obelisk was erected on the spina of the Circus Maximus in Rome in the autumn of that year, and is today known as the Lateran Obelisk, while the obelisk that would become the obelisk of Theodosius remained in Alexandria until 390, when Theodosius I (379395 AD) had it transported to Constantinople and put up on the spina of the Hippodrome here.

Each of its four faces has a single central column of inscription, celebrating Thutmose III's victory over the Mitanni which took place on the banks of the Euphrates in about 1450 BC. I thought that you might be interested in seeing the inscription up close, so I took one of our pictures, cropped out the inscription, enlarged it and put it in the scrollable window at left. This should make it easy for you to see the individual hieroglyphics.

The Obelisk of Theodosius is of red granite from Aswan and was originally some 95 feet tall, like the Lateran Obelisk. The lower part was damaged in antiquity, probably during its transport or re-erection, and so the obelisk is today only 65 feet high; the base adds another fifteen feet or so.

|

|

There are obvious traces of major damage to the pedestal and energetic restoration of it. Missing pieces have been replaced, at the pedestal's bottom corners, by cubes of porphyry resting on the bronze cubes already mentioned; the bronze and porphyry cubes are of identical form and dimensions.