|

June 3, 2017: The Old City of Istanbul |

|

June 1, 2017: An Afternoon Walk in Istanbul |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Istanbul |

Today, Fred and I will be heading out into Istanbul to see what we can see. Our first stop will be at the Dolmabahçe Palace, a site that we saw yesterday but did not have time to tour. Later, I hope that we'll be able to find out way to a section of the old city walls that are over on the Golden Horn. Jeffie will arrive late today, and tomorrow we will do things like the Topkapi Palace and the Hagia Sophia.

Dolmabahçe Palace

Our first stop today will be a palace that we saw yesterday. The Dolmabahçe Palace, located in the Besiktas district on the European coast of the Bosphorus, served as the main administrative center of the Ottoman Empire from 1856 to 1887 and 1909 to 1922.

Getting to the Dolmabahçe Palace

|

We crossed to the east side and then followed a major street as it curved around and down the hill, heading towards the sports stadium. Rather than continue all the way down on that street, though, we turned down a different street- which quickly turned into a street of stairs.

Of course, walking down the hill is easy; coming back up is the hard part. But maybe later in the day we'll be able to take the metro to Taksim Square or perhaps the underground funicular that comes up from the Bosphorus.

|

|

We'd been by here yesterday, but today we took another couple of pictures of the mosque, and you can see these at left. The Dolmabahçe Mosque was commissioned by queen mother Bezmi Alem Valide Sultan in the early 1800s. After she died, Sultan Abdülmecid (1823-1861), her son, continued to support the construction of the mosque. Upon completion in 1855, it was opened for prayer services.

We are going to go to the Hagia Sophia tomorrow with Jeffie, and it is a much bigger and much more elaborate structure, so we weren't particularly anxious to go inside this one.

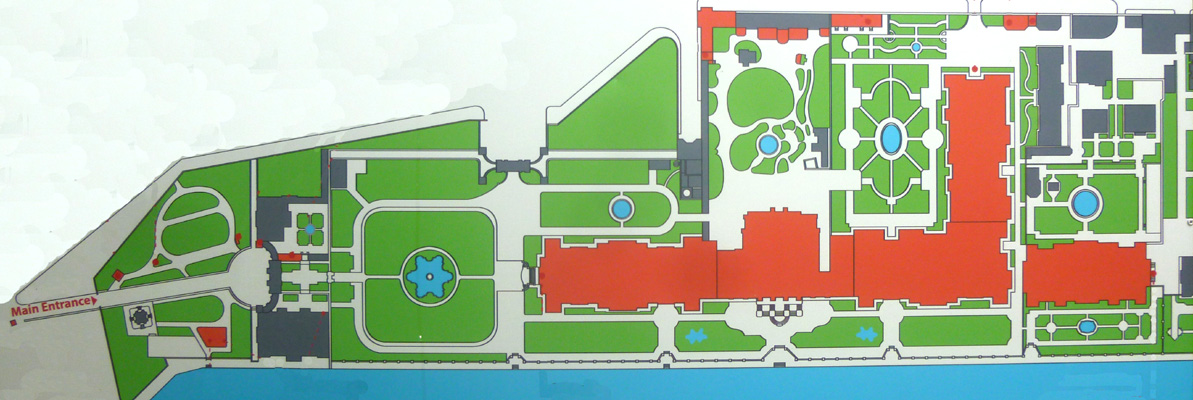

From the mosque, we walked a few feet north to the entry for the Dolmabahçe Palace. As we move into the Palace area, around the grounds and through some of the buildings, it may help you to have a reference diagram so you can see where we are at any given time. I took a picture of the palace diagram on the way in, and I'll use that graphic here. First, here is the full palace diagram:

|

We will cover most of the diagram as we tour the complex, so what I will do is take small portions of this diagram and use them to zero in on just where we were in the complex. You can always refer back to this diagram, though, if you wish (although I'll reserve extensive labeling for the diagram extracts).

The Entry to the Dolmabahçe Palace

|

|

The clock tower (Dolmabahçe Saat Kulesi) was erected in front of the Treasury Gate on a square along the European waterfront of Bosphorus next to the mosque. The tower was ordered by sultan Abdülhamid II and designed by the court architect Sarkis Balyan between 1890 and 1895. Its clock was manufactured by the French clockmaker house of Jean-Paul Garnier, and installed by the court clock master Johann Mayer.

Apparently, at least one of the sultans was "into" clocks, as one of the buildings we would tour a bit later was the palace clock museum.

I walked over to get our tickets, and then returned to Fred who had stayed in the central walkway. While I was getting the tickets, Fred got a nice view of some of the cannon and the mosque. Here are a couple more pictures Fred took as we were getting ready to head in to the palace complex through the Gate of the Sultan:

|

|

Just before we went in, I thought I would walk over to the Bosphorus to see what the view looked like.

|

I took the panoramic view at right looking north up the Bosphorus and alongside the palace itself. Later on, we found that there was a beautiful iron fence along the water and enclosing the palace, and two or three ornate gates to give palace occupants access to the water. I think if the sky had been clear this would have been a beautiful shot, but you'll have to use your imagination.

I went back over to rejoin Fred and together we approached the large, ornate Gate of the Sultan, the main entry to the palace complex.

|

The ornate central archway is flanked by two almost-identical wings. I don't know what the purpose of these buildings might have been when the palace was in use, but today they house administrative offices for the museum complex as well as the gift shops and other facilities. I did also take a "selfie" with myself and Fred just in front of the Gate of the Sultan and, as we passed through it, the decorated ceiling of the arch itself. The entire Gate of the Sultan was intricately decorated, as these pictures of the clock structure above the archway and the sides of the building wings show:

|

|

The Entry Gardens of the Dolmabahçe Palace

|

|

|

Today, this area acts as a vestibule for people who've bought their entry tickets for the palace complex. As you can see from the directional sign that was off to one side that all the areas of the palace/museum itself are through the second archway.

On either side of the main walkway were doorways through which one could get to the gift shops and the other facilities located here in the Gate of the Sultan.

We went through the second archway of the Gate of the Sultan to find ourselves in the Selamlik Garden- the area between the Palace and the Sultan's Gate. In the center of the garden is a six-pointed pool with a central fountain, and this is surrounded by manicured plantings. I stopped immediately to see if I could get my camera to create a panorama of the area I saw in front of me:

|

The pool and fountain was the central focus of this area; arrayed around it were quadrants of lawn bordered by plantings of what appeared to be begonias, small boxwood hedges, ground cover grasses and a great many roses of varying kinds (many of which Fred had not seen before).

|

At left is a nice picture of the fountain in the middle of the central pool. For the rest of the good pictures we took here in the Selamlik Garden, I think the best way to let you have a look at them is in a slideshow; that way, you can move through them quickly if you wish. The slideshow window is at right. To move from picture to picture, just use the little arrows in the lower corners of each slide. You can track your progress through the show using the index numbers in the upper left of each slide. Enjoy the Selamlik Garden! |

The other main feature of the Selamlik Garden area was the second major entrance to the palace grounds- the Treasury Gate- which is just north of the palace itself and which used to open out onto what is now Dolmabahçe Avenue.

|

To your right as you face the gate from the front of the palace there is a nice little garden area. It is a double circle of low boxwoods with begonias in the middle, and more small shaped boxwood "islands", and in the center of these is a sculpture of a lion. You can see this clearly in the picture at left, which was actually taken towards the end of our visit to the palace when the weather had cleared considerably. Earlier in the day, before we toured the palace, Fred took another picture of me and the lion sculpture.

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

From the Selamlik Garden area, we went over towards the Dolmabahçe Palace/Museum to get in line for our tour of the inside of the structure.

Touring the Selamlik at Dolmabahçe Palace

|

The construction, carried out by the Ottoman court architects and engineers, was hugely expensive. The cost of the entire complex was something close to $1.5 billion. This sum corresponded to approximately a quarter of the empire's tax revenue for a year. Actually, the construction was financed through debasement, by massive issue of paper money, as well as by foreign loans. The huge expenses placed an enormous burden on the state purse and contributed to the deteriorating financial situation of the Ottoman Empire, which eventually defaulted on its public debt in October 1875, with the subsequent establishment in 1881 of financial control over the "sick man of Europe" by the European powers.

The palace was home to six Sultans from 1856, when it was first inhabited, up until the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924. A law that went into effect on March 3, 1924 transferred the ownership of the palace to the national heritage of the new Turkish Republic. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first President of the Republic of Turkey, used the palace as a presidential residence during the summers and crafted some of his most important legislation here. Atatürk spent the last days of his medical treatment in this palace, where he died on November 10, 1938. Today, Dolmabahçe is managed by the Directorate of National Palaces, which is responsible to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. The only way to see the interior of Dolmabahçe is with a guided tour, and that's why we bought the tickets we did.

|

The Selamlik also encompassed the portion of the household reserved for the guests (from the root word selam, "greeting"), similar to the andronites (courtyard of men) in Ancient Greece, where guests would be welcomed by the males of the household. The harem is the portion for the family, not just for the concubines of the sultan as is the common interpretation today. Our ticket got us a guided tour of the Selamlik only, and we thought that might be enough to get a feel for what the entire palace was like.

The site of Dolmabahçe (from the Turkish "dolma" meaning "filled" and bahçe meaning "garden") was originally a bay on the Bosphorus which was used for the anchorage of the Ottoman fleet. The area was gradually reclaimed (filled in) during the 18th century to become an imperial garden. Various small summer palaces and wooden pavilions eventually formed a palace complex bounded by the Bosphorus on the southeast and a steep precipice on the northwest. This meant that once the Dolmabahçe Palace was built, a relatively limited space remained for the gardens that would typically surround such a palace.

|

Here is a good place to let you know that photography was not allowed in the palace. I always dislike it when places we visit don't allow photos. I guess I can understand museums not wanting professionals to photograph their works, or places where only flash is forbidden (because it might damage artwork or distract other visitors). But as you know I like to document trips like this as extensively as I can, and I would have liked to do a voice memo of what room we were in and then take a couple of photos of it. What I did, though, was take some photos surreptitiously. Doing so was going to be hit-or-miss; I wouldn't be able to compose the pictures or even take much time with them. So most of them wouldn't turn out well, and the ones that did wouldn't be as I would like them to be. That's why the pictures taken on this tour are not all that great; I actually had to discard most of them.

We had our orientation in this hall, where guests would first have waited before being led inside at the proper time by a palace protocol officer. Many of the pictures I did take were of ceilings, as it was relatively easy for me to hold my little camera out of sight and point it generally up. Even so, I often also got the appendages of people standing near me in these pictures. Here are a couple of half-way decent images of the ceiling decoration in this room:

|

|

The tour next went up the Crystal Staircase; it has bannisters made of Baccarat crystal and an impressive chandelier. I was able to get two pictures as we ascended the staircase, but they didn't do it justice. So, to the right of my two pictures is one that I am including courtesy of Wikipedia (to which, by the way, you should consider contributing):

|

|

|

The world's largest Bohemian crystal chandelier is in the Ceremonial Hall. The chandelier was assumed to be a gift from Queen Victoria, however in 2006 the receipt was found showing it was paid for in full. It has 750 lamps and weighs over 9000 pounds. Dolmabahçe has the largest collection of Bohemian and Baccarat crystal chandeliers in the world. Below are my picture from the Ceremonial Hall (left) and a stock photo from Wikipedia (right):

|

|

The palace possesses two 150-year-old bearskin rugs originally presented to the Sultan as a gift by Tsar Nicholas I. A collection of over 200 oil paintings is on display in the palace. From the very beginning, the palace's equipment implemented the highest technical standards. Gas lighting and water-closets were imported from Great Britain, whereas the palaces in continental Europe were still lacking these features at that time. Later, electricity, a central heating system and an elevator were installed.

One more stop that I can identify was in the Blue Hall; again, the one picture I was able to take is below, left, and a stock photo of the entire hall is to the right:

|

|

The Dolmabahçe palace is extensively decorated with gold and crystal; I found it hard to believe, but over 14 tons of gold were used to gild the ceilings and other surfaces and to fashion some of the furnishings for the palace. That amount of gold would today be worth some $450 million. You can see some of this gilding in one of the last two good pictures I took in the palace that are below:

|

|

Along the Bosphorus at Dolmabahçe Palace

|

|

I stopped here to make a movie, and you can watch it with the player at right.

So that you can see where we were in the palace when our tour ended, I want to include another extract of the diagram of the palace so I can make that clear.

|

|

The building has about one thousand feet of frontage along the Bosphorus; we had come out of the building about in the middle of that frontage, with most of the official, male-access area to our right (back toward the Gate of the Sultans); to our left, to the northeast, was the harem.

|

|

Once again, we took way too many pictures to include all of them here. Many of them were duplicates (since Fred and I were both taking pictures), and I have chosen the best of each pair. I have also whittled sixty pictures down to just ten or so, and those I have put into a slideshow.

You will see these pictures in the slideshow at left. To go from one picture to another, just use the little arrows in the lower corners of each picture. If you will refer to the index numbers in the upper left of each picture, you will be able to tell when you reach the end of the show.

We hope you enjoy these views of the Bosphorus side of Dolmabahçe Palace!

While we were standing by the Gate to the Bosphorus at the approximate middle of the building's Bosphorus side, I had my little camera put together a panoramic view:

At the north end of the Bosphorus face of the palace, we turned to walk along the side of the harem wing to head to the north side of the grounds for a visit to the clock museum.

The Dolmabahçe Palace Clock Museum

|

|

Gürgen emphasized that each of the clock in the museum had its own special features and history. Clocks presented in the museum's exhibition have French, English and Turkish origins. The clock master explained that the timepieces from the Turkish department are one of a kind do not have any copies anywhere in the world. "Wherever you go you will never find the same one," Gürgen said.

"I have work in the clock industry for 57 years" Gürgen explained, adding, "Usually this kind of a job always comes from family interest. My uncle was a clock master and he taught me all that I know."

Built between 1843 and 1856 on the European coast of the Bosporus, Dolmabahçe Palace was used as the palace and a presidential summer residence by the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. He spent his final days in the palace, where he died on November 10, 1938. The clock in the room where he died is famously still set to 9:05, the time of his passing.

Although photography was not nominally permitted in the museum, there was only one docent sitting near the entrance, so I was able to get quite a few pictures. These are in the slideshow at left. As usual, you can move through the pictures using the little arrows in the lower corners of each image, and you can track your progress with the index numbers in the upper left. Sadly, I had my camera on the wrong setting, so my resolution was not good enough for me to read and transcribe the plaques for you. But I hope you enjoy the pictures anyway! (I did photograph and transcribe a couple of plaques and have put them approximately where they belong in the slideshow.)

The Glass Pavilion and Harem Garden

|

(Click on Thumbnails to View) |

We made one other stop while we were here in the gardens north of the palace- the Glass Pavilion. In the Ottoman society, on certain days and occasions the Sultan's demonstrating his existence was considered important for emphasizing his justice and ruling. Alay Kosku (Procession Pavilion) at the Topkapi Palace carries a strong symbolic value by both representing the sultan's justice and by being a tower that the sultan observes and oversees his people. A 19th century version of the Procession Pavilion was built here, and it was called the "Glass Pavilion".

|

Much of the Pavilion was manufactured in the UK and imported. It has a dazzling lounge with sumptuous decor with gold leaf. The gilt figures of eagles in the corners of the pavilion ceiling, the pictures of wild animals and the magnificent fireplace are all very similar in style to the decoration in the Crimson Room in the Harem. The furniture includes a crystal piano of French manufacture and a crystal chair. Immediately adjacent to the pavilions there is a glass conservatory (which is the room I visited and which is shown at left); it has an iron framework. In the middle of this conservatory, from which the Glass Pavilion takes its name, there is a small pool with crystal fountain and a fireplace set back to back with the fireplace inside the pavilion itself.

One of the basic characteristics of this late Ottoman palace is the adaptation of the various architectural innovations that were then appearing in the West. One of these innovations is to be seen in the use of iron and glass in combination. The imposing ceiling over the Crystal Staircase in the palace is repeated in the Glass Pavilion conservatory. The result is a pavilion that continues traditions in Ottoman Palace architecture but modifies them with new materials and construction techniques.

The Glass Pavilion was built concurrently with the Palace, but was much different in its design concept and its implementation of currently building technologies. It is a unique structure, built as a coherent whole. While the conservatory is the nicest room in the Pavilion, the structure should be considered and evaluated in its entirety.

Wandering through the gardens, we came back to the front of the Selamlik, right by the Treasury Gate. We left the palace complex the same way we arrived, and thought that we would walk down the street to a restaurant for a bit of lunch before heading across town to see the Walls of Constantinople.

Lunch and the Istanbul Transit System

Leaving the palace, we thought that we would walk a little further north along the avenue to see if we could find a place to get some lunch.

|

We did continue along the avenue until we came to a commercial area where we found a little cafe that was serving traditional Turkish kabobs. Right across the street, Fred happened to notice a colorful wall mural- perhaps entited "The Umbrellas of Istanbul"?

From the restaurant, we walked back down Dolmabahçe Avenue and came back around the curve by the Dolmabahçe Palace on our left, and then continued on down the street past the Dolmabahçe Mosque.

|

You might be interested in what the Istanbul transportation system looks like, so I've put a map of it at right. I know it is too small to read, but that's not why I included it here. I wanted to show you that the system covers all three of the major areas of the city, running underneath the Bosphorus as well as over and under the Golden Horn to do so.

For reference, I've marked the location of Taksim Square, a major transfer point in the northern European section of the city. You can see that the system also serves the Golden Horn- the peninsula south of the Golden Horn waterway. (I know that gets a little confusing, with the peninsula and the waterway having the same name, but Istanbul residents don't seem to be confused, as one is always pretty sure which one someone else is talking about.)

The transit system goes to the Asian side as well, getting there via a tunnel from the Golden Horn and a bridge from the northern European section. We only used the transit system in a small area, though, and we should concentrate on that.

|

But on the map it looked as if it would be simpler to get to Taksim Square first, and then take the Green Line to Yenikapi and then the Red Line to Ulubath. Simpler, but, as it turned out, more expensive. The Turkish metro system is a little odd. In Berlin and Prague, if you bought a single trip ticket, you could make as many changes from one line to another as you wished or needed to in order to reach your destination, and this included underground and aboveground trains as well as trolleys and buses. You might be more familiar with the subways in New York City; there, too, you only pay once when you enter the system, and can literally ride all day all over the place for that one fare. You only have to pay again if you leave a station and reenter.

Here in Istanbul, you have to pass through a payment turnstile each time you transfer or switch modes of transportation. A computer system tracks your ticket, and can determine if you are continuing one trip or starting a different one, and it charges you accordingly each time you swipe the card. For example, to go from Taksim to Ulubath, we paid a first fare of about a dollar at the Taksim Station, and when we transferred at Yenikapi we were charged an additional 40 cents or so when we transferred to the Green Line. So the trip to Ulubath cost about a buck fifty. But if we had left the Yenikapi Station to eat lunch and then reentered to continue our journey, the computer would have seen the time difference and charged another one dollar fare. It was all very complicated, and very quickly we stopped trying to figure out why we were charged an extra fifty cents sometimes or thirty cents other times. One of these days, I will have to see if I can find a written explanation of how charges are calculated. The residents of Istanbul don't seem to care, as most of them buy monthly transit cards anyway.

To make a long story short, we did (after a couple of false starts and with the kind help of a transit policeman) find the funicular and take it up to Taksim Square. That's where Fred got these pictures:

|

|

We then transferred to the subway, took it to Yenikapi and transferred again to get to Ulubath, where we came up aboveground to find ourselves at the Walls of Constantinople- or at least what is left of them.

The Walls of Constantinople

The Walls of Constantinople are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of Constantinople (now Istanbul, of course) since its founding as the new capital of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great. With numerous additions and modifications during their history, they were the last great fortification system of antiquity, and one of the most complex and elaborate systems ever built. The walls underwent a major reconstruction in the 400s under Theodosius II, and it is these walls that we see today.

|

In their present state, the Theodosian Walls stretch for about 9 miles from south to north, from the "Marble Tower" (also known as the "Tower of Basil and Constantine") on the Propontis coast to the area of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus near the Golden Horn (waterway) in the Blachernae district. The walls were doubled, with the outer wall and moat being somewhat shorter, terminating and merging with the inner wall at the Gate of Adrianople. The section between the Blachernae and the Golden Horn does not survive, since the line of the walls was later brought forward to cover the suburb of Blachernae, and its original course is impossible to ascertain as it lies buried beneath the modern city.

From the Sea of Marmara, the wall first heads north and then turns sharply to the northeast, until it reaches the Golden Gate, at about 50 feet above sea level. From there and until the Gate of Rhegion the wall follows a more or less straight line to the north, climbing the city's Seventh Hill. From there the wall turns sharply to the northeast, climbing up to the Gate of St. Romanus, located near the peak of the Seventh Hill, now some 200 feet above sea level. From there the wall descends into the valley of the river Lycus, crosses that valley, and then climbs the slope of the Sixth Hill. The wall continues to the northeast, crossing very close to today's Ulubath metro stop, and then reaches the Gate of Charisius or Gate of Adrianople, now at an elevation of some 225 feet. The walls continue to the Blachernae, turn to the west and finally reach the coastal plain at the Golden Horn near the so-called Prisons of Anemas.

I have simplified all of this on the transit diagram with just the one angle to the northeast. Since we only explored the section of the wall between the Sixth Hill and the Gate of Charisius, I don't think it matters much what the exact route was. You can see that the walls did not extend across the Golden Horn to the new part of Istanbul north of the waterway; that section, of course, was hardly settled at all in Theodosius' time, and the waterway formed a natural barrier.

|

We took a lot of pictures this afternoon, and I want to organize them in sections. We first crossed the major street by the subway station (Adrian Menderes Boulevard) to where the walls (which are all in that green area you can see between the buildings and houses and the expressway that runs at an angle through the view) were snaking down a hill. That will be the first section of pictures. The next section will be again on the northeast side of the street where the walls snake up what I think is the Sixth Hill. The most interesting part of the walls is near the top of the Sixth Hill at the Gate of Charisius, and that will be the third section of pictures. The last group of pictures will be taken near the next major street (Fevzi Pasa Avenue) where we found some interesting neighborhoods and another mosque.

Both of those street cut through the walls; either those wall sections were removed and taken elsewhere or perhaps they were just demolished. I imagine the original streets were built at a time when historical and archaeological interests were not as important as they are now.

So if you want to come along with us, we can take a closer look at what is left of the Theodosian Walls, beginning with the segment south of Adrian Menderes Blvd.

The Theodosian Walls: Part 1

|

|

The tower structure shown here is the typical structure that is found all along the walls. I do not know how far apart these towers were, but it seemed, when I got up on the wall, that they might have been every hundred feet or so. I don't know if the doorway that you see here was part of the original wall, as it looked more modern than the wall above it or around it. We continued up the street and we could look back at the tower that we saw earlier.

|

Fred didn't follow me right away, but when I got up on top and saw how broad and flat the area was I called to him and he came up to join me. The picture he took of me at right is looking south along the top of the wall, and you can see a partially-ruined tower behind me.

Contrast the tower behind me with the photo that Fred took looking in the other direction back towards the intact tower that we'd seen earlier. It made me wonder why some towers stayed relatively whole while other deteriorated or disappeared entirely. I would imagine that over the centuries people would have used materials from the wall for other constructions, before protecting the walls would have become a priority.

Even now, when you think about it, there was nothing to prevent anyone from climbing up on the walls and maybe taking a souvenir. I could definitely see evidence that lots of people must come up here.

|

|

|

We are standing on the inner wall- a solid structure, between 15-18 feet thick and pretty much uniformly 40 feet high. This inner wall is faced with carefully cut limestone blocks, while its core is filled with mortar made of lime and crushed bricks. Between seven and eleven bands of brick, approximately a foot thick, traverse the structure, not only as a form of decoration, but also strengthening the cohesion of the structure by bonding the stone façade with the mortar core, and increasing endurance to earthquakes.

|

Each tower had a battlemented terrace on the top. Its interior was usually divided by a floor into two chambers, which did not communicate with each other. The lower chamber, which opened through the main wall to the city, was used for storage, while the upper one could be entered from the wall's walkway, and had windows for view and for firing projectiles.

Access to the wall itself was provided by large ramps along its side. The lower floor could also be accessed from the peribolos by small access doors. Generally speaking, most of the surviving towers of the main wall have been rebuilt either in Byzantine or in Ottoman times, and only the foundations of some are of original Theodosian construction. Furthermore, while until the Komnenian period the reconstructions largely remained true to the original model, later modifications ignored the windows and embrasures on the upper store and focused on the tower terrace as the sole fighting platform.

So what you are actually seeing in our pictures of the towers are mostly reconstructions; I guess that is why some of them are in pretty good shape, while older ones, not having been reconstructed, are not.

|

|

Actually, the picture at the far right is interesting as you can see one of the towers from the lower, outer wall, and you can see part of the structure of that wall as well.

The outer wall was 6 feet thick at its base, and featured arched chambers on the level of the terrace; it was topped with a battlemented walkway, reaching a height of some 30 feet. Access to the outer wall from the city was provided either through the main gates or through small doorways on the base of the inner wall's towers. (That solves the mystery I alluded to earlier in one of our first pictures of the wall this afternoon- the doorway below one of the towers.)

The outer wall had towers too, situated approximately midway between the inner wall's towers, and acting in supporting role to them. They were also spaced irregularly, on average about 150 feet apart. Only 62 of the outer wall's towers survive. With few exceptions, they are square- about 30 feet tall and 12 feet on a side. They also had a room with windows on the level of the terrace, crowned by a battlement. Some had small doors allowing access to the outer terrace. The outer wall was a formidable defensive edifice in its own right: in the sieges of 1422 and 1453, the Byzantines and their allies, being too few to hold both lines of wall, concentrated on the defense of the outer one.

The Theodosian Walls: Part 2

|

You can see the Sixth Hill better in this picture that I took once we got to the other side of the street. The next portion of our walk is going to be right up that street you can see climbing the hill right alongside the ruins of the walls. Ahead of us up the street we could see the 16th-century Sultan Mihrimah Mosque at the top of the hill.

There were a number of interesting aspects to this section of the wall. One was that up on top of the wall we could see that the towers in this section were mainly ruins- not nearly as complete as those we saw in the first section of our walk. Here is one of those ruined towers.

|

|

|

So I've just put them in another slideshow so you can move through them easily and at your own pace. That slideshow is at left.

To move from picture to picture, just use the little arrows in the lower corners of each picture. You can track where you are in the show with the index numbers in the upper left corner of each image.

About halfway up the hill, there was a place where the wall had deteriorated down to just about ground level, so I went through the opening to stand in the middle of the walls. I thought I would try a panoramic view from here; it is below:

|

The Theodosian Walls: Part 3

|

The Gate of Charisius is the second most important gate in the land walls, after the Golden Gate, which is at the southern end of the walls at the Sea of Marmara. This is the gate through which Mehmed the Conqueror entered the city with ceremony on May 29th, 1453. A plaque on the wall commemorates this event. It is the highest gate in the land walls, here atop the Sixth Hill- over 200 feet above sea level. It took its name from an early Byzantine monastery that used to be nearby.

The Byzantines named it "Porta Harisius", but also called "Andrinopolis". The reason was that the roads leading to Edirne started here. The name of Edirne in the Roman era was Hadrianopolis, after its founder Hadrian. One branch of the Mese (the main road of Istanbul at the Byzantine era) reached this gate, connecting Istanbul to Edirne. Because of this Turks continued to use the name "Edirnekapi" (Edirne Gate).

After the conquest of Istanbul, the sultans ceremoniously left by this gate when going on military campaigns to Europe. Afterwards the gate was also ceremoniously used when the sultans were to be throned after "the girding" in Eyup Sultan Mosque.

Within and outside of the walls that were the starting point of the road leading to Edirne in the Ottoman period, there were some tablets regarding the maintenances in the Ottoman era. In the earthquake of 1999 the southern tower was destroyed and later rebuilt. In this picture that Fred took of me outside the Gate of Charisius, I am standing on the terrace outside the walls. The dropoff in front of me goes down to where the moat would have been.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Theodosian Walls: Part 4

|

|

When we came up to the base of the walls, we discovered that there was another street right at the base of the walls, and both the walls and the street extended into the distance. We'd been told that the section of the wall that we walked was in particularly good shape, and at least the inner wall seemed to be pretty much intact in this area, but I have no way of knowing how far north or south these intact walls and towers might go.

We walked along the walls for just a short ways before taking some local streets through the neighborhood just east of the walls. Fred didn't want to re-cross the avenue without a light, so we were heading a block or two east where we'd seen a controlled crossing.

When we got back around to the avenue, we found a little plaza that had a fountain (one of those multiple-jetted, timed affairs) and also a monument to Mehmed the Conqueror. Sure enough, when we got to the crossing, we found that it was equipped with what we could easily figure out from the pictures was a pedestrian crossing control.

On the other side of the street, we walked through a small square and then passed in front of the Sultan Mihrimah Mosque. Then we went back to the street along the walls and headed back down to the Ulubath metro stop and boarded a train back to Taksim Square. I might point out that when the metro crosses the Golden Horn, it does so on a bridge, rather than going through a tunnel. Crossing the bridge, I was able to take a couple of good pictures; in the second one, you can see the Galata Tower in the distance:

|

|

Jeffie was supposed to arrive at the hotel about 7PM, so we hung around there until she arrived. After she got settled, the three of us went out for a walk and eventually had some dinner at a restaurant we'd seen on Istiklal Avenue. We looked forward to seeing and doing a lot with her tomorrow.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

June 3, 2017: The Old City of Istanbul |

|

June 1, 2017: An Afternoon Walk in Istanbul |

|

Return to the Index for Our Visit to Istanbul |