|

July 14, 1999: Waterfalls in Yosemite |

|

July 12, 1999: Flying to California/Yosemite National Park |

|

Return to the Index for Our California Trip |

Today, we are going to begin with a visit to the Mariposa Grove of Redwoods, located south of the main valley of the Yosemite. Then, we will spend the afternoon in two national parks south of Yosemite and east of Fresno- Sequoia and King's Canyon.

The Mariposa Redwood Grove

|

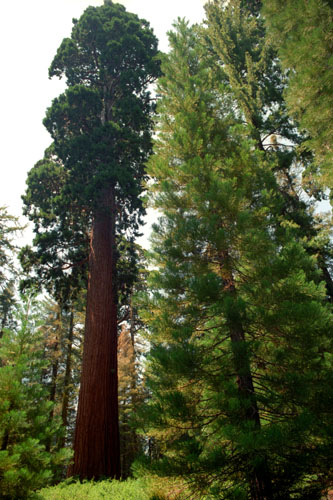

The Mariposa Grove, near Yosemite's South Entrance, contains about 500 mature giant sequoias. Giant sequoias are perhaps the largest living things on Earth.

Although the oldest giant sequoias may exceed 3,000 years in age, some living specimens of the ancient bristlecone pine (found in the mountains east of Yosemite and at Great Basin National Park in Nevada, among other places) are more than 4,600 years old.

In actuality, the tallest trees we know are cousins of the giant sequoia- the Coast Redwood. As their name implies, they grow along the California coast, and the best places to see them are at Muir Woods National Monument and Redwood National Park. We may have an opportunity to go to Muir Woods on this trip but, if we don't, these giant sequoias will be an excellent stand-in.

Mariposa Grove is in the southernmost section of Yosemite National Park, and is the largest grove of Giant Sequoia trees in the park, with several hundred huge mature examples of the tall and wide tree. Two of Mariposa Grove's famous trees are among the 25 largest Giant Sequoias in the world.

The Mariposa Redood Grove was first discovered by American and European white men in 1857 when settlers and explorers Galen Clark and Milton Mann found the tall tree grove. They named the redwood grove after Mariposa County, California, where the grove resides

We got to the parking area fairly early, and set off to follow the marked trail that would lead us through the grove.

|

Although the largest trees are well into the grove, even the ones at the parking area were impressive. One popular misconception is that Sequoiadendron giganteum are the oldest living things, but they aren't. Some individual living specimens of the ancient bristlecone pine, Pinus aristata, are more than 4,600 years old! The oldest Giant Sequoias may exceed 3,000 years.

And Giant Sequoias aren’t the tallest living things, either. The related coastal redwoods, Sequoia sempervirens, grow higher, up to 368 feet. The “Sierra redwoods” top out around 310 feet; the tallest in the Mariposa Grove is about 290 feet. Giant Sequoias don’t even have the greatest basal diameters. The Montezuma cypress, Taxodium mucronutum, of Mexico may exceed 50 feet, while the largest known Giant Sequoia is just over 40 feet in basal diameter.

So why did these trees capture the attention of the world when discovered by western Europeans in the early 1850’s? Simply stated, while neither the tallest nor thickest trees, in total volume the Giant Sequoias are the largest living things known to humans.

|

While we did find a number of young Sequoias along the road/trail, there were not many back in the forest. The reason is a complex one, and humans have had their impact. To germinate, Sequoia seeds have three requirements: (1) some direct sunlight, (2) adequate moisture and (3) bare mineral soil. This is why there were younger trees along the road- the road's construction created a perfect seedbed by opening up the forest floor to sunlight, increasing moisture along the roadsides and providing bare mineral soil on the road’s spoil banks.

But why are young Sequoias so sparse away from the road? Shortly after these trees were discovered, in a well-intended effort to protect them, people began suppressing natural fires. More shade-tolerant trees, such as white firs, incense-cedars and sugar pines, quickly spread over the forest floor, reducing sunlight, competing for moisture and blanketing the mineral soil with their needles and debris. It became impossible for Sequoia seedlings to get started.

Only lightning-caused fires, usually occurring in late summer, could reduce the competition form other evergreens and burn away the leaf litter, leaving a thin layer of nutrient-rich ash over the mineral soil. The heat from a fire dries some of the ever-present green Sequoia cones high in the mature trees, causing a shower of fresh seeds to fall after the fire onto a perfectly prepared seedbed. Beginning in November, snowstorms slowly bury the Mariposa Grove in an ever-deepening white blanket. As the snowpack melts the following spring, sunlight, moisture, fresh seeds, ash and mineral soil combine to create a Sequoia nursery.

This dependency on natural fires for Sequoia reproduction was not understood until the early 1960’s. By then, 100 years of unburned forest litter and young evergreens had accumulated, producing a massive fuel load. Had lightning ignited a fire under these unnatural conditions, an intense crown fire could have occurred, possibly killing even the largest trees. To redeuce this abnormal fuel supply and promote Giant Sequoia reproduction, the National Park Service began a series of “prescribed burns,” deliberately set and closely monitored by rangers during spring and fall. When the forest returns to a more natural state, these management fires will probably be discontinued. Then nature can resume its cycle of lightning-caused ground fires every seven to 20 years.

|

That tree had mostly weathered away, but its root structure were clearly visible. Anyway, the roots of both fallen trees were similar. Sequoias don’t have deep tap roots; instead, the roots spread out near the surface to capture water. While the roots are usually no deeper than six feet, they fan out more than 150 feet, providing a stable base on which to balance the massive trunk. That's one reason visitors are asked to stay on the road or the trails; doing so minimizes soil compaction that damages these surface roots.

All of this information was immensely interesting to read as we walked along the trail.

|

There are two "levels" of cones in each tree. The lower-level cones produce pollen (male). At the crown of a mature Giant Sequoia may be thousands of green cones at any one time. Each cone contains about 200 tiny flat seeds, roughly 1/4-inch in length and resembling a rolled oak flake. These female cones grow on the upper branches. Given this vertical separation, how do the trees reproduce?

Like most conifers, Giant Sequoias depend on the wind. Late winter storms bring strong winds that carry the pollen from the lower branches of one tree to the upper branches of others, continuing the genetic mixing necessary for healthy reproduction. This vertical separation reduces the likelihood that the tree could pollinate itself.

We continued walking along the road past these gigantic trees stopping to take pictures at their bases, or to explore some of the trees that had fallen. There was a path that actually led inside one of them, and at another you could get up close to examine a cross-section of the trunk (that tree having been cut through after it fell just so you could see inside the wood). Click on the thumbnail images below to see some of the pictures we took along the trail:

|

There were not only the sequoias to look at, but the other trees and plants in the forest. Fred, ever the horticulturist, found an interesting wildflower that he couldn't identify; you can see it here.

| ||||

Mr. Dowd’s announcement was undoubtedly greeted by a hail of unkind comments about his mental stability. He left the camp but was not deterred. After an appropriate absence, he returned, announcing that he had just shot an enormous grizzly bear and needed five strong men to help carry the meat back to camp. There was no bear; all Dowd wanted were witnesses to confirm his story. With that confirmation, the story of the giant Sequoias was out.

The Mariposa Grove Giant Sequoia named Grizzly Giant is between 1900-2500 years in age: the very oldest redwood tree in the grove. In 1932, it was claimed to be the fifth largest tree by volume in the world, but other trees were subsequently found to be even larger; it currently has a volume of 34,000 cubic feet, only the 25th biggest redwood tree. It is over 210 feet tall, and has a heavily buttressed base with a circumference of 92 ft or a diameter of 30 feet. Grizzly Giant's first branch from its base is itself 6 feet in diameter- itself larger than almost all the non-Sequoia trees in the forest.

The trail through the grove was something over a mile; at the end of it there is now a museum, although I don't recall it being there when we visited this year. The walk took us 90 minutes or so before we were back at the parking area. The grove was really neat- well worth the small amount of backtracking we had to do to visit it. We got back in the car to head south to Sequoia and King's Canyon National Parks.

Sequoia National Park

|

Sequoia National Park is one of two National Parks in the southern Sierra Nevada mountains; it was established on September 25, 1890. The park spans 631.35 square miles, and encompasses a vertical relief of nearly 13,000 feet. Located in Sequoia is the highest point in the contiguous 48 United States, Mount Whitney, at 14,505 feet. The park is southwest of and contiguous with Kings Canyon National Park; the two are administered by the National Park Service together as the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

|

We had already spent a good deal of time at the Mariposa Grove, so we didn't want to do the entire hike between the two groves. We did want to see the General Sherman Tree, though, and we got an excellent picture of it- the one at right.

The first European settler to homestead in the area was Hale Tharp, who famously built a home out of a hollowed-out fallen giant sequoia log in the Giant Forest next to Log Meadow. Tharp allowed his cattle to graze the meadow, but at the same time had a respect for the grandeur of the forest and led early battles against logging in the area. From time to time, Tharp received visits from John Muir, who would stay at Tharp's log cabin.

Tharp's attempts to conserve the giant sequoias were at first met with only limited success. In the 1880s, white settlers seeking to create a utopian society founded the Kaweah Colony, which sought economic success in trading Sequoia timber. However, Sequoia trees, unlike their coast redwood relatives, were later discovered to splinter easily and therefore were ill-suited to timber harvesting, though thousands of trees were felled before logging operations finally ceased.

The National Park Service incorporated the Giant Forest into Sequoia National Park in 1890, the year of its founding, promptly ceasing all logging operations in the Giant Forest. The park has expanded several times over the decades to its present size; one of the most recent expansions occurred in 1978, when grassroots efforts, spearheaded by the Sierra Club, fought off attempts by the Walt Disney Corporation to purchase a high-alpine former mining site south of the park for use as a ski resort. This site was annexed to the park to become the highest-elevation developed site within the park and a popular destination for backpackers.

We enjoyed our short time in Sequoia National Park, walking through the giant trees. Having taken quite a few pictures at the Mariposa Grove, we took only a few more here, and you can see two of the best ones below:

|

|

King's Canyon National Park

|

Kings Canyon had been known to white settlers since the mid-19th century, but it was not until John Muir first visited in 1873 that the canyon began receiving attention. Muir was delighted at the canyon's similarity to Yosemite Valley, as it reinforced his theory regarding the origin of both valleys, which, though competing with Josiah Whitney's then-accepted theory that the spectacular mountain valleys were formed by earthquake action, Muir's theory later proved correct: that both valleys were carved by massive glaciers during the last Ice Age.

Then United States Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes fought to create the Kings Canyon National Park. He hired Ansel Adams to photograph and document this and other parks, which in great part led to Congressional action in 1940 that combined the General Grant Grove with the backcountry beyond Zumwalt Meadow into the National Park. For 50 years afterward, some wanted to build a dam at the western end of the valley, while others wanted to preserve it as a park. The debate was settled in 1965, when all the areas in question were added to the Park.

|

The remainder of Kings Canyon National Park, which comprises over 90% of the total area of the park, is located to the east of General Grant Grove and forms the headwaters of the South and Middle Forks of the Kings River and the South Fork of the San Joaquin River. Both the South and Middle Forks of the Kings Rivers have extensive glacial canyons.

One portion of the South Fork canyon, known as the Kings Canyon, gives the entire park its name. Kings Canyon, with a maximum depth of 8,200 feet, is one of the deepest canyons in the United States, carved by glaciers out of granite. This canyon is the only other portion of the park accessible by car. Both the Kings Canyon and its Middle Fork twin, Tehipite Valley, are deeply incised, U-shaped glacial gorges with relatively flat floors and towering granite cliffs thousands of feet high.

To the east of the canyons are the high peaks of the Sierra Crest, which attain an elevation of 14,248 feet. This is classic high Sierra country: barren alpine ridges and glacially scoured lake-filled basins- accessible only in mid-year via foot and horse trails.

For our afternoon here in King's Canyon National Park, we basically drove the north highway from Grant Grove Village, where we visited the panoramic point and the General Grant Tree, past numerous viewpoints for the canyons, along the South Fork of the Kings River (where we took a great many pictures) and all the way to Roaring River Falls and Zumwalt Meadow where the road ended. The details of each stop aren't important, so the question is how to show you the pictures we took. For some of them, I have put little thumbnail images on the park map below; to see the full-size picture, just click on its thumbnail image:

|

The road paralleled one river or another for quite a while, and we stopped frequently to take pictures of the streams and some little waterfalls, and I want you to be able to look at these pictures.

|

Our drive through King's Canyon National Park was extremely enjoyable. It would have been nice to have been able to bring our camping gear with us so we could have taken advantage of the beautiful campgrounds that we saw. But we contented ourselves with the spectacular scenery.

Late in the afternoon, we found ourselves at the end of the road, ready to turn around and head back to Fresno and our motel for the night. We will have one more day in the National Parks tomorrow.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

July 14, 1999: Waterfalls in Yosemite |

|

July 12, 1999: Flying to California/Yosemite National Park |

|

Return to the Index for Our California Trip |